6 Biotypes of Depression and Anxiety Identified by Scientists

Depression is a condition that requires a personalised approach, and growing research is helping identify which treatments work best for different people.

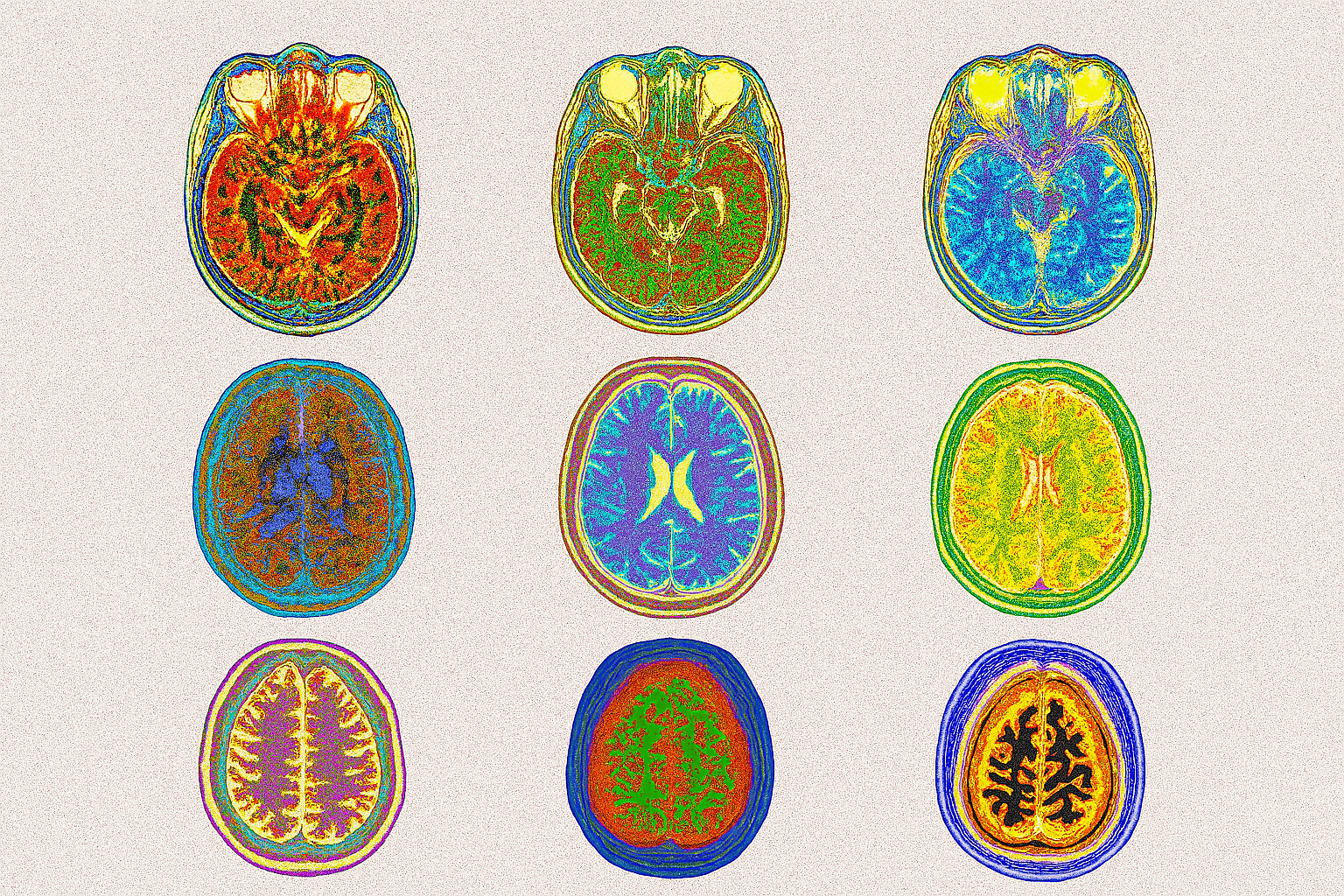

A recent groundbreaking brain imaging study published in Nature Medicine has revealed six distinct “biotypes” of depression. These are not based on symptoms alone, but on patterns reflective of brain activity and connectivity measured with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), offering a new perspective and potential pathways to treat depression and related anxiety disorders.

The research, led by Stanford scientists and involving over 800 participants, used advanced brain scans and AI-powered analysis of the functional data to identify these subtypes — groups of people whose brain circuits show different patterns of activity and connectivity. Each depression biotype was shown to have its own distinct neural fingerprint, behavioural traits, and unique response to therapy. A biotype’s name is an abbreviation of the key brain circuits involved, with plus (+) or minus (−) signs indicating increased or decreased activity/connectivity.

D = Default Mode Network (involved in self-reflection, daydreaming, and internal thoughts)

S = Salience Network (detects important stimuli and switches attention)

A = Attention Network (focuses on external information)

N = Negative Affect Circuit (processes negative emotions like threat or sadness)

P = Positive Affect Circuit (processes positive emotions like happiness)

C = Cognitive Control Circuit (manages self-control, decision making, inhibition)

“The Overconnected Default Mode”

Biotype DC⁺SC⁺AC⁺

169 participants of the study were characterised by heightened connectivity within the brain’s default mode, salience, and attention circuits. This biotype may contribute to excessive self-focus and thought rumination (repetitive negative thinking). People in this group performed slower on tasks involving emotional recognition and sustained attention — but responded well to behavioural therapy (42% responded, 25% achieved remission).

In everyday life, this type may show up as overthinking, difficulty shifting focus from negative events, and emotional overwhelm — but also may offer a high level of insight into thought patterns and potential for strong therapeutic gains.

“The Disconnected Attention Network”

Biotype AC⁻

161 participants with reduced connectivity in the attention network. This biotype showed faster reaction times but higher error rates, especially on attention and inhibition tasks. It had the highest average age and lower cognitive control. These participants showed poorer response to behavioural therapies like CBT compared to other groups.

This biotype may manifest as a person who is easily distracted, makes impulsive decisions, and has difficulty staying focused, though often paired with quick mental responses and fast reactions.

“Emotionally Heightened”

Biotype NSA⁺PA⁺

This group of 154 participants showed hyperactivity in the brain’s emotional circuits during exposure to both sad and happy stimuli. They reported more severe symptoms of anhedonia (loss of pleasure) and rumination, making them more emotionally reactive. Treatment response data were less detailed, but their distinct emotional processing sets them apart and suggests a unique treatment need.

This profile may reflect people who feel emotions deeply and intensely — both the highlights and lowlights that life contains — and may be more sensitive to emotional triggers in their environment.

“The Overcontrolled Brain”

Biotype CA⁺

The largest group of 258 participants was marked by overactivation in the cognitive control network. This biotype showed high levels of anxious arousal, anhedonia, and sensitivity to threat. They also showed signs of heightened self-regulation efforts — possibly overcompensating for emotional dysregulation — and made more errors in executive function tasks. Encouragingly, they responded well to treatment with the antidepressant medication venlafaxine/Effexor (a SNRI), with 64% of the biotype showing improvements and with 40% of these individuals experiencing remission.

In real life, this biotype might look like high-functioning anxiety: people who work hard to stay in control, often at the expense of emotional flexibility.

“Blunted Threat & Control Response”

Biotype NTCC⁻CA⁻

Only 15 participants belonged to this group, making it the smallest one. This rare group showed underactive responses to threat, weak cognitive control, less rumination and faster reactions to sad faces, suggesting a blunted emotional and control response. More research is needed to understand their treatment pathways, but their atypical profile could hold clues for novel therapies.

This type may reflect people who seem emotionally dissociated or mentally disconnected in deeply stressful situations — potentially protecting them from intense distress but making it harder to engage fully in therapy.

“Neurotypical-Like Profile”

Biotype DXSXAXNXPXCX

Unlike the others, this group of 44 participants did not show major dysfunction across brain circuits. However, they still experienced symptoms of clinical depression and performed more slowly on tasks involving threat cues. They may benefit from more personalised diagnostics beyond circuit data.

This biotype reminds us that even when brain scans look “normal,” people can still struggle — highlighting the need for nuanced, person-centred approaches to care.

Why Biotypes of Depression Matter

Depression isn’t one-size-fits-all. These brain-based biotypes can be considered “transdiagnostic” — spanning multiple traditional diagnostic categories, reflecting the multifaceted nature of depression and mood disorders. Instead of grouping people by symptoms like “major depressive disorder” or “social anxiety,” this approach targets the how and why behind those symptoms — at the level of brain circuitry.

Researchers also found that treatment outcomes varied by biotype, pointing toward a future where your depression treatment could be matched to your brain’s unique wiring. While the research is still emerging, it opens the door to a more personalised, precise, and hopeful way of understanding mental health.

Understanding your brain’s activity fingerprint could be the key to more effective, lasting recovery. And science is getting closer to making that a reality.