From Baby Blues to Postpartum Depression: Warning Signs and Treatment Options

Bringing a baby into the world is often described as pure joy — but for many parents, the postpartum weeks feel unexpectedly heavy. Up to 80% of new mothers experience the so-called “baby blues”, marked by sudden mood swings, irritability, and tearfulness that usually fade within two weeks.

For some, though, the sadness doesn’t fade. Instead, it deepens into postpartum depression (PPD) — a serious condition affecting nearly 17,7% of women worldwide. Knowing where the line lies between baby blues and PPD is more than medical semantics. It’s often the difference between a temporary low and a long-lasting struggle that requires treatment and support. So how do you tell one from the other?

What Are Baby Blues

The so-called baby blues — also known as maternity blues or postnatal blues — are the most common emotional shift after childbirth. They usually appear within the first few days after delivery (often around day 3) and may last up to two weeks. Typical baby blues symptoms include sudden crying spells, irritability, mood swings, anxiety, restlessness, difficulty sleeping despite exhaustion, loss of appetite, and poor concentration. Many mothers describe it as feeling “overwhelmed” or “not themselves,” even while experiencing joy at having a newborn.

On Reddit, Meg, 28F, opened up about the first signs of baby blues she experienced:

“I started feeling very down and overwhelmed about 2 days after birth. But my baby was in the NICU for 4 days, so I thought it was the stress of that. Then it got so much worse when we brought him home, and I felt so guilty. I cried all the time”.

What causes baby blues?

The exact cause is still debated, but researchers point to a mix of biological and psychological factors:

- Hormonal shifts — the sharp drop in estrogen and progesterone after birth destabilises mood-regulating systems.

- Sleep deprivation — irregular rest in the first days after delivery worsens irritability and emotional lability.

- Physical recovery — pain, exhaustion, or complications after labour can intensify vulnerability.

- Emotional adjustment — the sudden responsibility of caring for a newborn and changes in identity can trigger anxiety.

How common are they?

Prevalence estimates vary widely depending on the culture and study design. A global meta-analysis reported an average rate of 39%, with figures ranging from 13.7% to 76% across different countries. Some local studies suggest lower rates — for example, in Indonesia, about 25% of mothers reported baby blues.

While the condition is temporary, it’s not trivial. Evidence shows that around 13% of cases can progress into postpartum depression if left unrecognised or unsupported. This makes early awareness crucial: distinguishing between short-lived baby blues and the warning signs of a more serious disorder can protect both mother and child.

From Baby Blues to Postpartum Depression

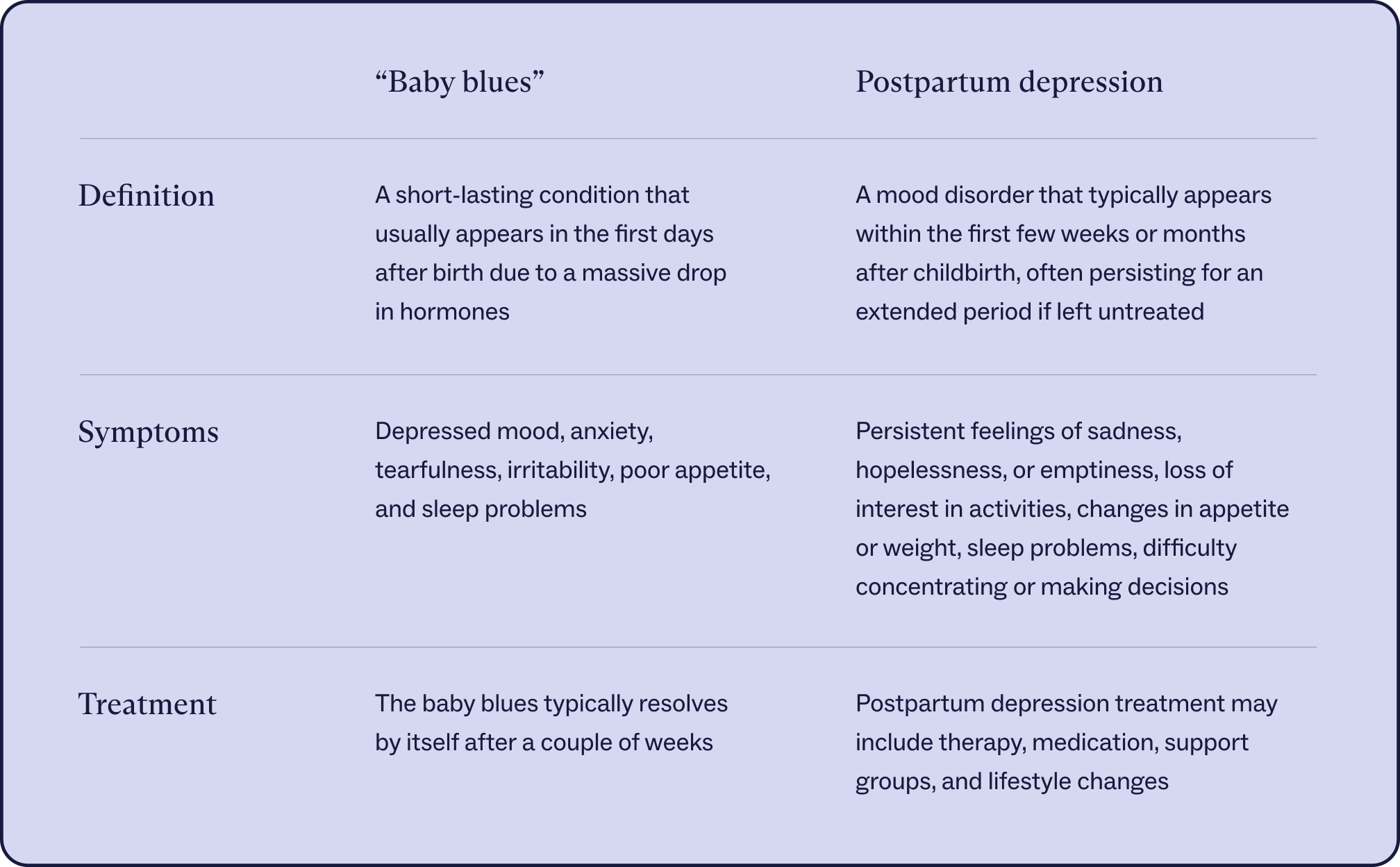

Most new mothers expect some mood swings after birth, but the line between baby blues and postpartum depression (PPD) is not always obvious. Baby blues typically fade within two weeks. PPD, in contrast, is a diagnosable depressive disorder that may last for months if untreated and often requires professional care.

Not every case of baby blues turns into depression. But specific vulnerabilities make this transition more likely:

- Hormonal sensitivity and biology — the sudden drop in estrogen and progesterone after birth, combined with changes in cortisol, oxytocin, and thyroid hormones, can destabilise mood in mothers who are biologically predisposed.

- Genetic predisposition — variations in the serotonin transporter (SERT), oxytocin receptor, and estrogen receptor genes have been linked to increased vulnerability to PPD.

- History of mood disorders — women with previous depression, anxiety, or a family history of psychiatric illness face higher risks of escalation.

- Unresolved antenatal anxiety, stress or trauma — high levels of anxiety during pregnancy strongly predict persistent postpartum mood disorders.

- Delayed or absent diagnosis — nearly half of mothers with PPD never receive a clinical diagnosis, allowing symptoms to deepen and persist.

- Social and economic stressors — poverty, partner conflict, lack of support networks, or experiences of domestic violence can intensify what begins as transient sadness.

- External crises — global stressors such as the COVID-19 pandemic doubled the prevalence of PPD, showing how environmental pressures can block recovery from baby blues.

PPD is not just “more intense baby blues.” While blues usually resolve naturally, postpartum depression can interfere with bonding, strain relationships, and affect a child’s cognitive and emotional development. Left untreated, it can persist for months and even increase risks for long-term psychiatric conditions in both mother and child.

Signs of Postpartum Depression You Shouldn’t Ignore

Some emotional turbulence is normal after birth. But when specific symptoms linger or worsen, they become red flags for PPD. These signals go beyond the expected fatigue of new parenthood and point to a condition that needs medical attention.

Red flags to look out for:

- Persistent low mood that doesn’t lift after two weeks.

- Loss of interest or joy in daily life or in bonding with the baby.

- Irritability, anger, or emotional volatility that feels out of control.

- Crippling exhaustion unrelated to the baby’s sleep schedule.

- Appetite and sleep disruptions — too much or too little.

- Overwhelming guilt or worthlessness.

- Brain fog and difficulty concentrating.

- Intrusive or dark thoughts, including about self-harm or, rarely, harming the baby.

Research shows links to impaired bonding, cognitive delays, and emotional difficulties in children of mothers with depression. Suicide remains one of the leading causes of maternal death in the first year postpartum, underscoring the urgency of seeking support. With treatment, however, recovery is highly likely: up to 80% of women with PPD fully recover within a few years.

Overlap and Related Conditions

Postpartum mood changes don’t always stop at baby blues. Other conditions can surface in the same fragile weeks after birth:

- Postpartum anxiety — marked by relentless worry about the baby’s safety, racing thoughts, or panic attacks. Unlike blues, it doesn’t fade on its own and often coexists with depression, making it harder to spot.

- Postpartum psychosis — extremely rare but serious. It can bring hallucinations, paranoia, or confusion within days of delivery. With quick medical care, recovery is possible, but it requires urgent attention.

- Post-adoption depression — even without the biological shifts of pregnancy, adoptive parents may feel overwhelmed, guilty, or detached after bringing a baby home. The transition itself — identity changes, pressure, and lack of sleep — can trigger symptoms much like postpartum depression.

These overlapping conditions remind us: postpartum mental health is not a single diagnosis but a spectrum. Awareness helps parents and families take early, informed action.

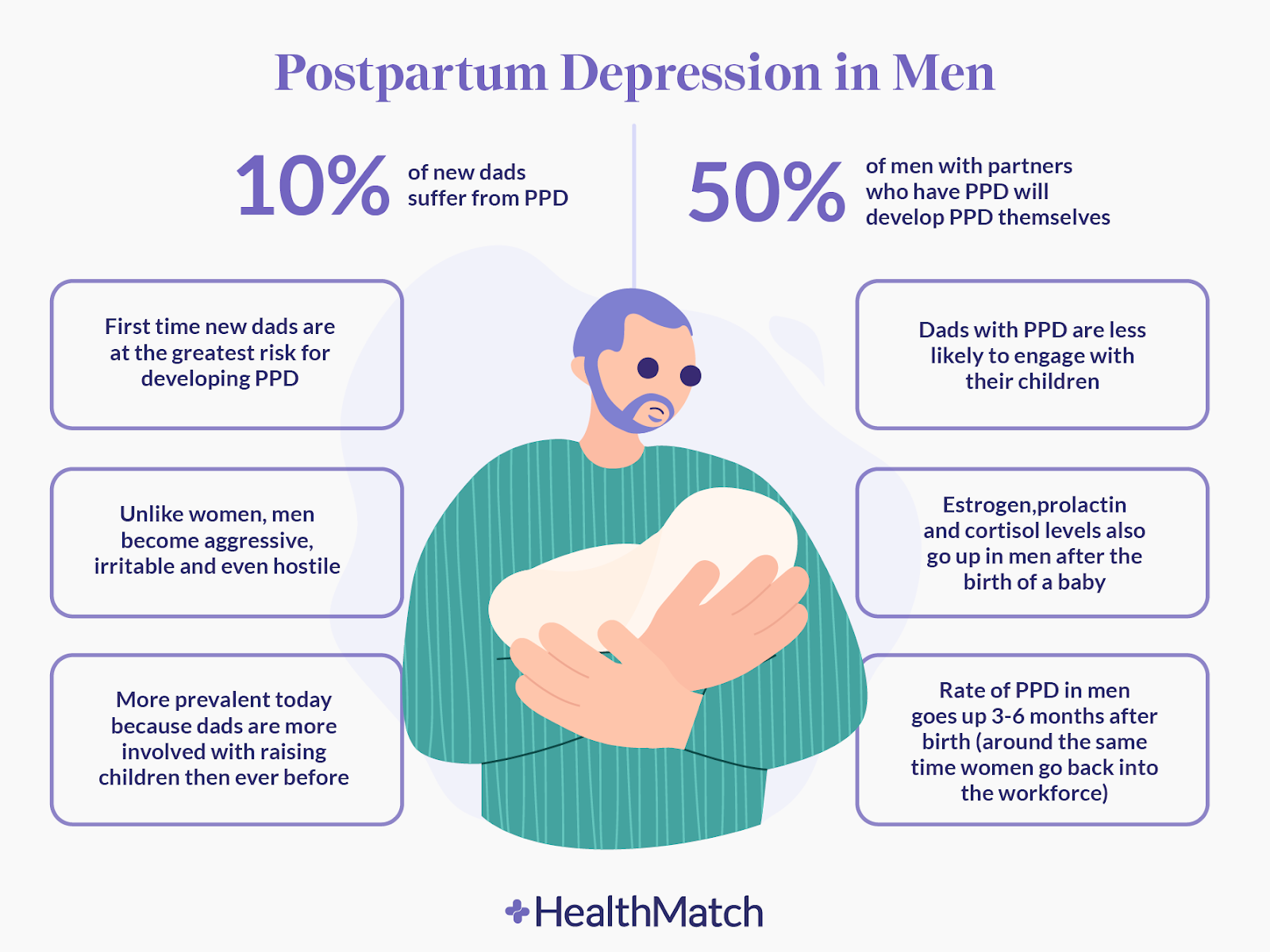

Postpartum Mental Health in Men

When a baby arrives, most eyes are on the mother’s recovery. But new fathers can struggle too. Studies suggest that around 8-10% dads experience postpartum depression, with symptoms most likely to appear between the third and sixth month after birth. And if a mother is also depressed, the father’s risk almost doubles.

Male postpartum depression doesn’t always look like “classic” sadness. Instead, dads may:

- Snap or get irritated easily

- Withdraw from family or friends

- Throw themselves into work, screens, or alcohol

- Struggle to connect with the baby

- Feel guilty, indecisive, or just emotionally “numb”

Because these signs don’t fit the stereotype of depression, they often fly under the radar.

The reasons are a combination of biological factors and life stress. Fathers go through hormonal shifts too — testosterone can dip, while prolactin and cortisol rise to support bonding. Add to that sleepless nights, money worries, or relationship strain, and even the most prepared dad can find himself overwhelmed. A history of depression, either in him or his partner, makes things even harder.

The good news: treatment works. Therapy (like CBT or couples counselling) helps many fathers get back on track. Medications such as SSRIs can be an option for moderate to severe cases. Beyond the clinic, simple changes — better sleep, shared parenting, supportive workplaces, even paid paternity leave — can make a big difference in dealing with “paternity blues”.

Beyond the Blues: Treatment and Awareness

Postpartum depression doesn’t go away with willpower alone — but it is highly treatable. Therapy is often the first step: cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT) help reframe thoughts and restore balance in daily life. For moderate or severe cases, medication — particularly SSRIs such as sertraline — remains the standard, while new options like brexanolone bring hope for faster relief.

Beyond medicine, recovery often hinges on support — from partners, families, peer groups, and even workplaces. Father-inclusive programs and policies, such as paid parental leave, can significantly lower risks and improve outcomes.

“The one thing I would tell new parents about the baby blues is to take care of yourself. Yes, you have a brand new priority in your baby, but you also need to prioritise self-care so that you can be the best for your baby,” — Meg, 28F, describing her recovery journey for States of Mind.

Awareness makes it easier for parents to recognise when something is wrong and reach out for help. The earlier support begins, the better the chances of full recovery for the whole family.

FAQ

- What are baby blues?

Baby blues are short-term emotional changes after birth — mood swings, crying spells, irritability, and anxiety — that affect many new mothers.

- When do baby blues start?

Most women experience symptoms between days 2 and 5 postpartum.

- How long do baby blues last?

They usually start around day 3 after birth and fade within 2 weeks.

- What are the symptoms of baby blues?

Typical signs include sudden crying, irritability, anxiety, poor sleep, and difficulty concentrating.

- Baby blues vs postpartum depression — how can you tell the difference?

Baby blues are mild and temporary; postpartum depression (PPD) is stronger, lasts weeks or months, and disrupts daily life.

- What causes postpartum depression?

It’s triggered by a mix of factors: hormonal shifts, genetic predisposition, history of depression or anxiety, and social stress like lack of support or financial strain.

- Can men have baby blues, too?

Yes. Around 1 in 10 fathers experience postpartum depression, often showing irritability or withdrawal rather than sadness.

- What is the most popular PPD treatment?

Therapy (CBT or IPT) and antidepressants like SSRIs are effective. Social and workplace support also improves the chances of recovery.