High-Functioning Anxiety: The Silent Struggle Behind Productivity

- High-functioning anxiety often hides behind productivity and perfectionism but leads to chronic stress and fatigue.

- It’s a sub-clinical anxiety pattern, not a DSM-5 diagnosis — real, just harder to detect.

- The same traits that fuel success can drive burnout and self-criticism.

- At work, anxiety often looks like overperformance and loss of work-life balance.

- Calm, not control, is the goal. CBT, mindfulness, and healthy boundaries can restore stability.

From the outside, it looks like momentum: the coworker who never misses a deadline, the friend who’s “fine,” the parent who keeps every plate spinning. Inside, it often feels different: racing thoughts, tight shoulders, and a humming dread that rest will make everything fall apart. Clinicians and writers describe this pattern as high-functioning anxiety — not a formal DSM-5 diagnosis, but a lived, sub-clinical form of worry that can masquerade as competence Psychologists frame it as the “fight” version of anxiety: instead of avoiding, people overperform. The result can look like success, until it quietly erodes sleep, relationships, and a sense of ease. Let’s map the signs, roots, and evidence-based ways to dial down the noise without dimming your drive.

What Is High-Functioning Anxiety?

At first glance, high-functioning anxiety doesn’t look like anxiety at all. It seems like composure: people who manage full schedules, meet deadlines, and appear perfectly in control. Beneath that calm, though, lies a steady undercurrent of worry, tension, and self-doubt. This hidden form of anxiety allows people to function (sometimes even excel) while quietly fighting symptoms that never fully switch off.

Clinicians often describe high-functioning anxiety as a sub-clinical anxiety disorder: real, but harder to detect. It doesn’t appear as a standalone condition, instead, it overlaps with traits of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). The difference lies in visibility. Someone with high-functioning anxiety may experience the same physical restlessness, muscle tension, or racing thoughts as others with GAD. Yet they continue to perform, often using structure and control as coping mechanisms.

Psychologist Dr. Adam Borland calls this the upgraded version of anxiety: “With high-functioning anxiety, there tends to be more of a fight response, where an individual pushes themself to work harder in order to combat the anxiety.”

That fight is often mistaken for drive. As Thriveworks explains, high-functioning anxiety can make you look calm and capable on the outside, but inside you’re in constant motion — driven not by passion, but by fear of what happens if you stop.

Culturally, it fits neatly into A-Player personality mold: ambitious, perfectionistic, relentlessly productive. Society rewards that behavior, making the distress behind it easier to miss. Over time, the pattern can blur the line between healthy ambition and hidden exhaustion, leaving many to wonder whether they’re thriving or simply coping well.

Causes and Risk Factors

Anxiety isn’t simply an emotion — it’s a biological, psychological, and cultural pattern. In those with high-functioning anxiety, this pattern often forms a paradox: the same traits that make someone organized, disciplined, and capable also sustain chronic tension beneath the surface.

Brain and body

Neuroimaging studies show that anxiety involves disrupted signaling between the amygdala (the brain’s alarm system) and the prefrontal cortex (responsible for regulation and control). When this pathway stays overactive, the body remains in a constant state of alert, even in safe situations. Elevated cortisol levels reinforce this “always on” response. A large-scale meta-analysis in Journal of Anxiety Disorders confirmed consistent amygdala–prefrontal dysconnectivity in people with anxiety disorders. Over time, this rewiring makes calm feel unnatural, stillness becomes something to fight, not embrace.

Inherited vulnerability

Anxiety often runs in families, suggesting a genetic component. Medical and physiological conditions such as thyroid disorders, arrhythmia, or hormonal imbalances can further heighten anxiety risk. According to Medical News Today, these medical factors interact with brain chemistry and life stress, creating a ground for sub-clinical anxiety to take root.

Personality traits

Many with high-functioning anxiety identify with traits like perfectionism, conscientiousness, introversion, or relentless self-evaluation. These qualities often drive success but can easily cross into rigidity. A recent study notes that perfectionistic individuals use control as an anxiety buffer, until control itself becomes exhausting. The fear of failure, even over small details, keeps the nervous system on high alert.

Family and childhood

The roots often begin in first years of life. Many adults with high-functioning anxiety grew up in families where emotional connection was conditional: where praise came for achievements, not authenticity. Clinical evidence shows that achievement-based worth and emotionally distant caregiving foster chronic self-doubt and overresponsibility. What starts as striving for approval becomes a lifelong habit of self-pressure.

Cultural reinforcement

Modern culture rewards exactly the behaviors anxiety thrives on: productivity, perfectionism, and self-sacrifice. From social media to corporate metrics, “doing more” is treated as virtue. As the Mayo Clinic notes, people with high-functioning anxiety often overwork, volunteer excessively, and “look for clues on how society defines success.” The result is burnout disguised as purpose — and a culture that mistakes exhaustion for excellence.

How High-Functioning Anxiety Differs From Other Types of Anxiety

High-functioning anxiety sits on the same spectrum as other anxiety disorders — generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), panic disorder, PTSD, but manifests differently. The shared physiological core remains the same: excessive worry, restlessness, muscle tension, and fatigue. The distinction lies in behavior and visibility.

People with high-functioning anxiety rarely appear anxious. Instead of avoiding stressors, they overengage: working harder, planning more, and holding themselves to impossible standards.

The Yerkes–Dodson law helps explain this pattern: a moderate level of anxiety can enhance performance, but sustained high levels lead to exhaustion and decline. For many, that edge between productivity and burnout becomes their baseline.

High-functioning anxiety can also overlap with traits of OCD — repetitive checking, overthinking, and control loops that momentarily ease worry but reinforce it long-term. The result is cognitive overload: constant mental rehearsal and self-monitoring mistaken for discipline.

Key Differences in Anxiety Types

- How it looks: Ordinary anxiety is easy to spot — panic, avoidance, overwhelm. High-functioning anxiety hides behind calm and control.

- How it reacts: One shuts down under stress; the other copes by working harder and doing more.

- What drives it: General anxiety fears danger. High-functioning anxiety fears imperfection or failure.

- Where it leads: The first limits action. The second leads to exhaustion and burnout.

- How it’s seen: One is treated with concern. The other is often mistaken for ambition.

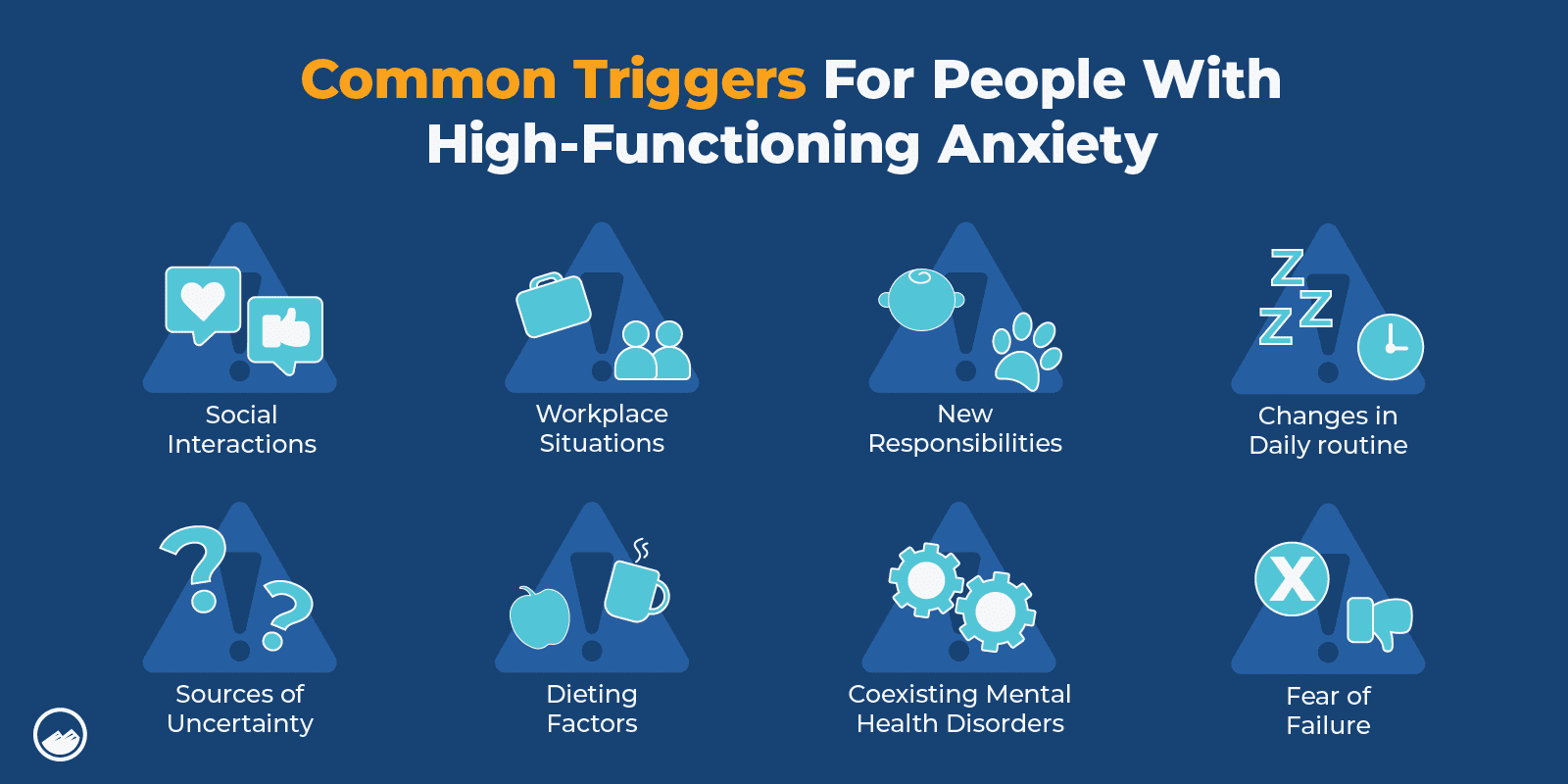

How It Shows Up in Daily Life: Signs and Symptoms

High-functioning anxiety rarely looks chaotic — it looks busy. On the surface, it’s deadlines met, plans made, and routines kept. Underneath, it’s excessive worry, tension, and the quiet fear that everything will fall apart if you stop moving.

Emotional and behavioral signs

People often describe living with a brain that won’t turn off. Overthinking every decision, replaying conversations, and expecting the worst become daily habits. Perfectionism and people-pleasing show up as self-protection: if you do everything right, maybe the anxiety will quiet down. But it never quite does.

Physical symptoms

The body keeps pace with the mind’s overdrive. Common symptoms include headaches, stomach distress, muscle tightness, “rubbery legs,” tingling in hands or feet, and chronic insomnia. People with high-functioning anxiety often push through these sensations instead of slowing down, mistaking discomfort for discipline.

Workplace patterns

At work, high-functioning anxiety can look like excellence: the colleague who always says yes, stays late, and delivers perfectly formatted presentations. Psychologist Irina Gorelik notes, “Performing well at work is a way to cover up how much you’re struggling internally.” Short-term praise reinforces the cycle; the more you achieve, the more rest feels undeserved.

Personal costs

In private, the cracks show: irritability, fatigue, withdrawal, or difficulty being present in relationships. Constant self-criticism eats at confidence, while the body starts to protest in subtler ways: tension, shallow breathing, burnout disguised as motivation.

The burnout loop

As Psychology Today puts it, high-functioning anxiety is the fuel that keeps the fire going when someone would otherwise burn out. Over time, that fire stops illuminating and starts consuming, leaving behind exhaustion disguised as success.

Strengths and Challenges: The Double-Edged Sword

High-functioning anxiety always hides behind the mask: what looks like competence from the outside can hide an exhausting inner dialogue. It’s the paradox of being both high-achieving and quietly overwhelmed.

Strengths that shine

Many traits tied to high-functioning anxiety are genuine assets, especially in fast-paced or high-responsibility environments:

- Discipline and reliability: people with high-functioning anxiety often deliver exceptional results and keep strict routines.

- Empathy: their sensitivity to others’ emotions can make them thoughtful friends, partners, and leaders.

- Attention to detail: focus and perfectionism help them anticipate problems before they arise.

- Drive and motivation: anxiety often becomes momentum, the force that turns fear into productivity.

Challenges beneath

The same traits that make high-functioning individuals dependable can also drain them:

- Chronic self-criticism and fear of failure that drive constant overworking.

- Restlessness and inability to relax, even after completing tasks.

- Exhaustion and emotional burnout from doing too much for too long.

- Shame and silence: many fear losing credibility by admitting they struggle, which reinforces the cycle of perfectionism.

The work paradox

At work, anxiety can look like excellence. Professionals with high-functioning anxiety often appear hyper-productive, overprepared, and endlessly available. But the drive to stay “on” can slowly erode focus, creativity, and satisfaction.

Research on occupational burnout shows that chronic stress and perfectionism predict emotional exhaustion and decreased cognitive flexibility. Over time, this can lead to “presenteeism” or “quiet quitting” — showing up physically but running on autopilot. The person who seems most dependable may secretly be the most depleted.

Many overachievers describe their anxiety as both an edge and a trap: it fuels performance, but it never lets them rest. In environments that reward speed and control, the anxious mind becomes a high-efficiency machine. However, the same focus and empathy that drive high-functioning individuals can thrive in calmer conditions — with rest, therapy, and support. Letting go of society-defined success and redefining it as balance, presence, and self-acceptance is what makes achievement really sustainable.

Treatment and Coping Strategies

Managing high-functioning anxiety means learning not to suppress anxiety. The goal is to build a nervous system that can rest as well as perform. Evidence-based therapies and lifestyle shifts are at the core of that process:

Therapy

Psychotherapy remains the first-line treatment. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has the strongest evidence base for anxiety disorders — a meta-analysis of 269 studies found it significantly reduces both anxiety and depression symptoms. CBT helps identify distorted thought loops (“If I’m not perfect, I’ll fail”) and replace them with balanced reasoning. Solution-Focused Brief Therapy (SFBT) can complement CBT by focusing on existing coping tools and small, achievable goals.

Medication

When symptoms persist, medication may be prescribed under medical supervision. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) such as sertraline, fluoxetine, or escitalopram are first-line pharmacological options for generalized anxiety disorder. Short-term use of buspirone or benzodiazepines can reduce acute anxiety but should be used cautiously due to risk of dependence. Medication works best when combined with ongoing psychotherapy and behavioral regulation.

Lifestyle regulation

Lifestyle choices directly influence anxiety physiology. Regular aerobic exercise reduces cortisol and increases endorphins — measurable effects observed in multiple randomized controlled trials. Proper sleep hygiene, balanced nutrition, and reduced caffeine or alcohol intake also stabilize mood and stress response.

Mindfulness and grounding

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) has strong empirical support for lowering anxiety and physiological arousal. Psychologists encourage self-acceptance rather than avoidance: “Instead of being afraid of anxious feelings, say: ‘I have anxiety, and that’s OK.’ My anxiety doesn’t make me a bad person — it’s just how my body and mind react, and I can deal with it.” Daily deep breathing and progressive muscle relaxation help deactivate the sympathetic “fight-or-flight” response and strengthen the parasympathetic “rest-and-digest” system.

Support systems

Social connection is one of the most reliable buffers against anxiety. Peer and family support reduces perceived stress and improves emotional regulation. Ultimately, recovery begins with redefining what “functioning” means. Calm is not laziness. Balance is not failure. And rest, for people who’ve spent years outrunning anxiety, is the most radical form of resilience.

Related reading

High-Functioning Anxiety vs Stigma

High-functioning anxiety challenges the idea of what struggle looks like. Many people assume that if you’re productive, organized, or successful, you can’t be suffering. It’s a misconception that keeps countless individuals from seeking help until burnout forces them to stop.

In recent years, a growing number of public figures have begun speaking about their own experiences, helping to dismantle that silence. Barbra Streisand has openly discussed the stage fright that sidelined her career for years before therapy helped her return to performing. MLB pitcher Zack Greinke took time away from professional baseball to address his anxiety and later became a vocal advocate for mental health in sports. The Atlantic’s Scott Stossel, author of “My Age of Anxiety”, has written candidly about living with panic and perfectionism — proof that vulnerability can coexist with professional excellence.

As psychotherapist Linda Hubbard from the Mayo Clinic puts it, “I believe that anxious people are awesome. They just need to believe in themselves, and develop tools to become more confident and self-accepting.” Destigmatizing high-functioning anxiety means replacing judgment with empathy at home, at work, and in culture at large. The new definition of strength is knowing when to reach out, rest, and redefine success in more humane terms.