Do Personality Tests Help Us Understand Ourselves — or Put Us in Boxes?

From the early days of psychology to the endless online quizzes, personality tests have always had a grip on us. They show up everywhere — in career coaching, team-building sessions, even dating profiles. And it’s not just for fun: about 80% of Fortune 500 companies use personality tests when hiring or developing staff.

We turn to this type of assessment because they promise something we’re all secretly craving — a sense of identity, a shortcut to belonging, and the comforting idea that someone can map our personalities with just a few clever questions. The catch? When the four-letter label from MBTI becomes louder than the person, it’s worth asking whether the test is helping us grow — or just teaching us to shrink.

The Science Behind Personality Tests

Psychologists have been debating for decades how best to capture personality. At the centre of this debate are two big camps: trait theory and type theory.

Trait theory — Science’s Favourite

The backbone of most academic research. Its most trusted tool is the Big 5 personality test, also called the Five Factor Model, which measures five broad traits on a spectrum: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (often abbreviated to OCEAN). Unlike fixed categories, these traits are continuous, meaning you can be more or less extroverted, more or less agreeable, and so on. Decades of cross-cultural studies show that the Big Five consistently predict patterns in behaviour, health, and even job performance.

Type theory — People’s Favourite

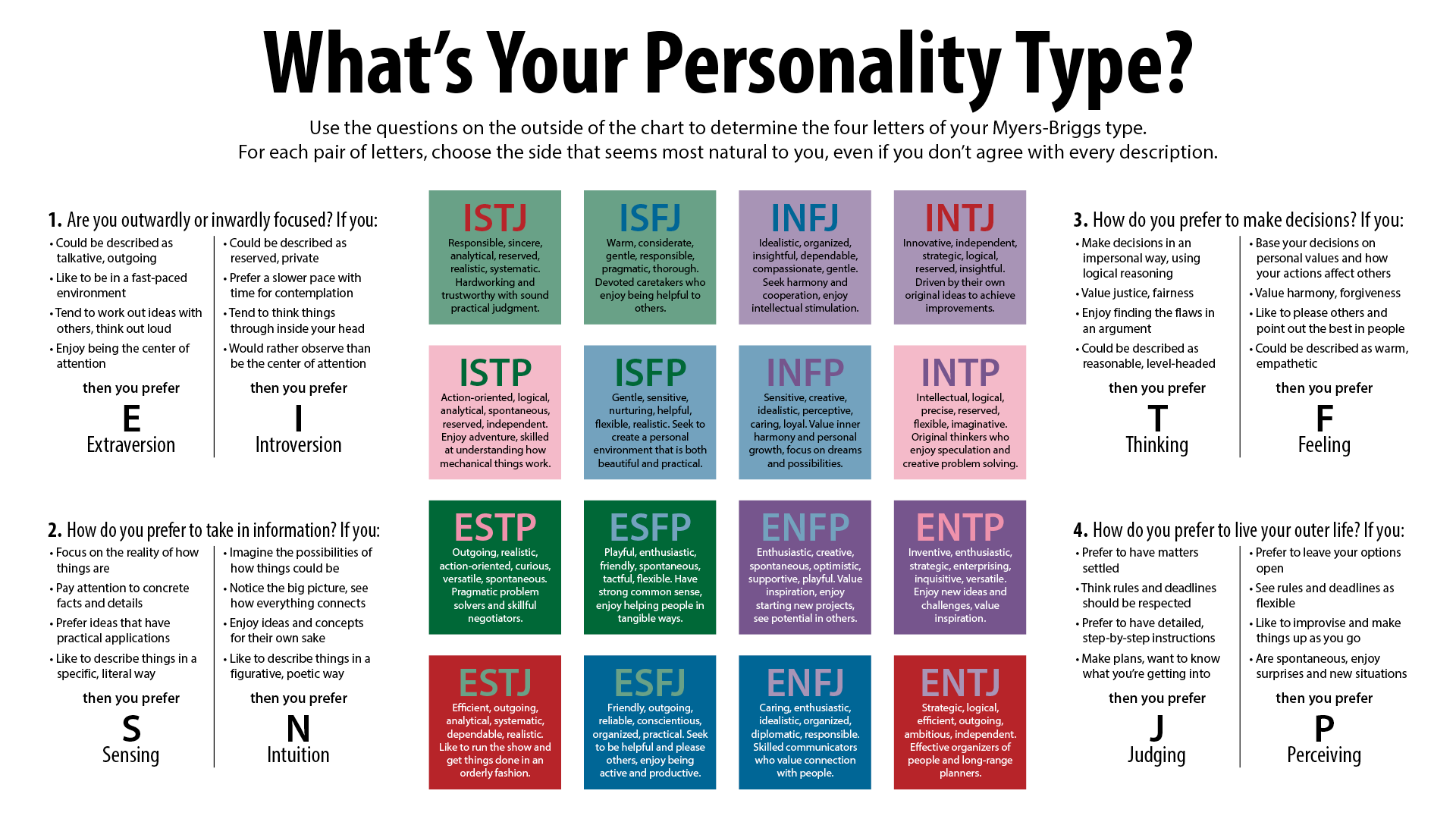

On the other hand, this one categorises people rather than placing them on a spectrum. A notable example is the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). It groups people into 16 personality types based on 4 dichotomies: Extraversion–Introversion, Sensing–Intuition, Thinking–Feeling, and Judging–Perceiving. The MBTI’s popularity is undeniable — it’s used in workplaces, coaching, and pop culture worldwide. The Myers-Briggs Foundation argues that the instrument has “decades of research” showing strong reliability and validity, with meta-analyses reporting compelling coefficients for most scales and recent studies confirming solid test–retest stability.

Still, critics are not convinced. Many academics point out that MBTI’s binary categories can oversimplify personality, and that results sometimes change when people retake the test (an issue called “Test-Retest Reliability”). By contrast, the Big Five captures nuance and tends to show stronger predictive power in research. This tension — categories versus spectrums — is at the heart of the scientific debate.

The Middle Ground

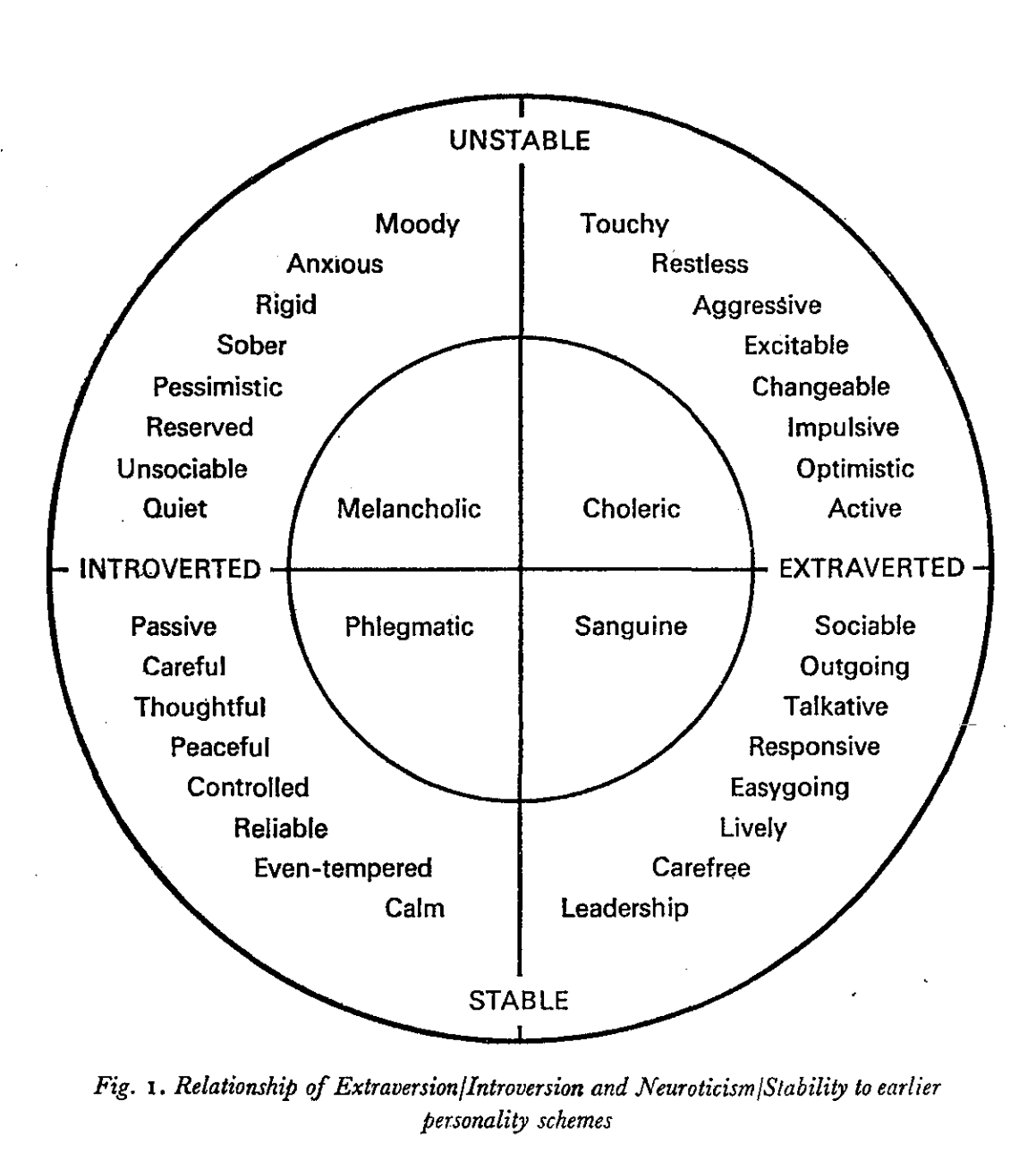

Some tools do manage to bridge the gap between science and practice. The Eysenck personality test, for example, is rooted in psychophysiology, linking traits like extraversion and neuroticism to measurable differences in brain activity. Because of this neurobiological grounding, psychologists often view it as a more rigorous model than entertainment-driven quizzes — and as an important stepping stone toward the Big Five.

6 Personality Tests Everyone Knows

Myers-Briggs Personality Test (MBTI)

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator is the one almost everyone has heard of. Developed during World War II by Katharine Cook Briggs and her daughter Isabel Briggs Myers, it classifies people into 16 types based on four dichotomies: Extraversion–Introversion, Sensing–Intuition, Thinking–Feeling, and Judging–Perceiving. In theory, MBTI reflects psychological preferences — how people gain energy, process information, make decisions, and structure their lives. The test became wildly popular in business, coaching, and even online dating because it is easy to explain and fun to use. Millions of people now identify themselves with a four-letter code as if it were part of their identity.

Proponents cite decades of research and meta-analyses, which report reliability coefficients in the 0.80 range for most scales, as well as recent studies confirming test–retest stability above this range in large international samples. Critics, however, argue that the MBTI oversimplifies personality into rigid boxes and does not predict behaviour as effectively as research-based models like the Big Five. People often get different results when they retake it, and the binary categories fail to capture the nuance of continuous traits. Still, its cultural staying power is undeniable.

Enneagram Personality Test

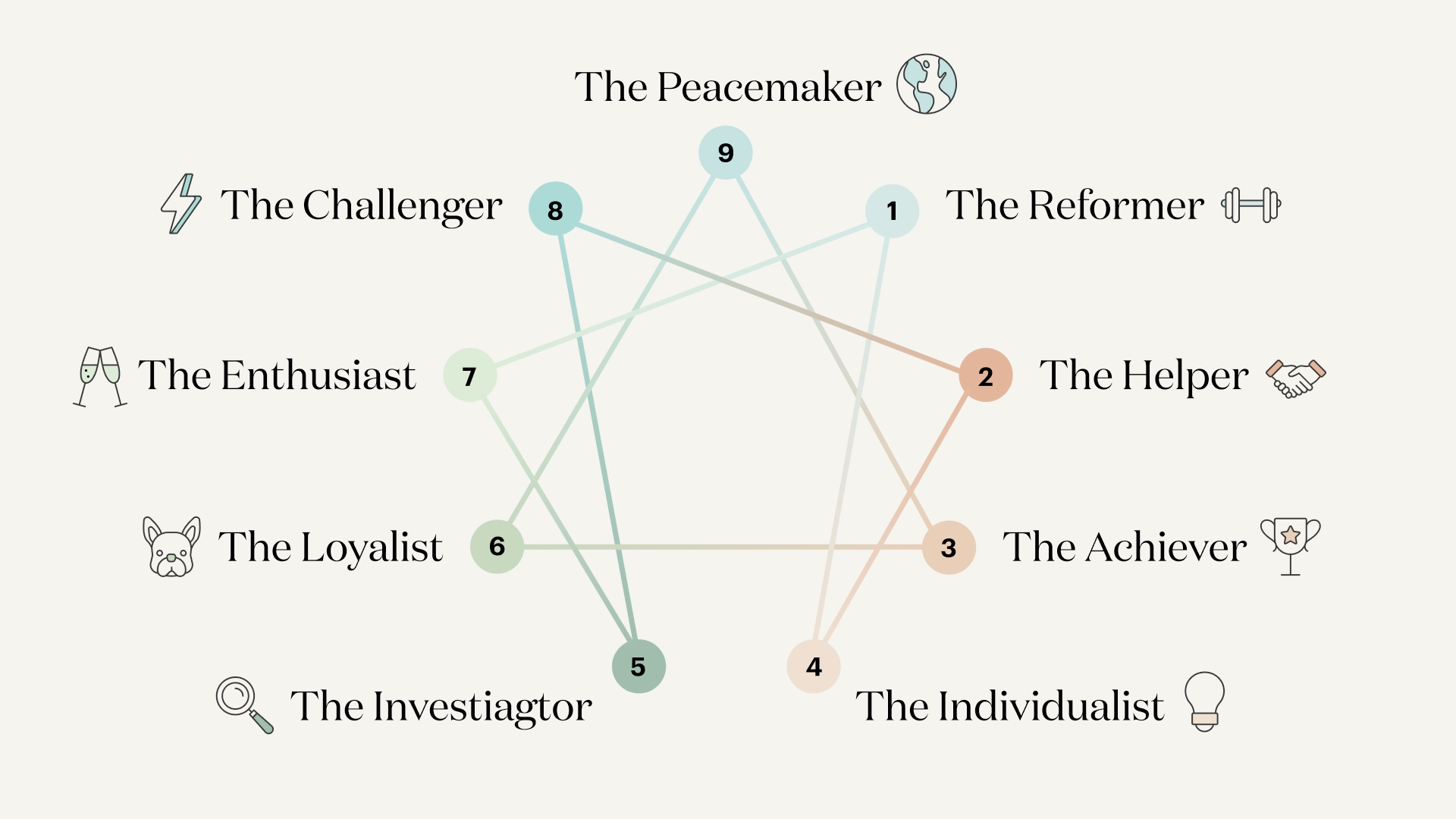

The Enneagram Test offers a very different lens. Instead of dichotomies, it describes 9 types, each defined by a core motivation and a corresponding fear. For example, Type Ones strive for integrity, Type Threes crave achievement, and Type Sevens seek joy and avoid pain. People love the Enneagram because it tells a story: not just who you are, but why you behave the way you do, and how you can grow.

Coaches and therapists often use it because it provides language for inner struggles, vulnerabilities, and strengths. Despite this popularity, scientific validation is thin. Studies suggest some overlap with Big Five traits, but factor analyses often fail to confirm the neat nine-type structure. Psychologists caution that its spiritual and mystical origins make it more of a narrative framework than a validated measurement tool.

DISC Personality Test

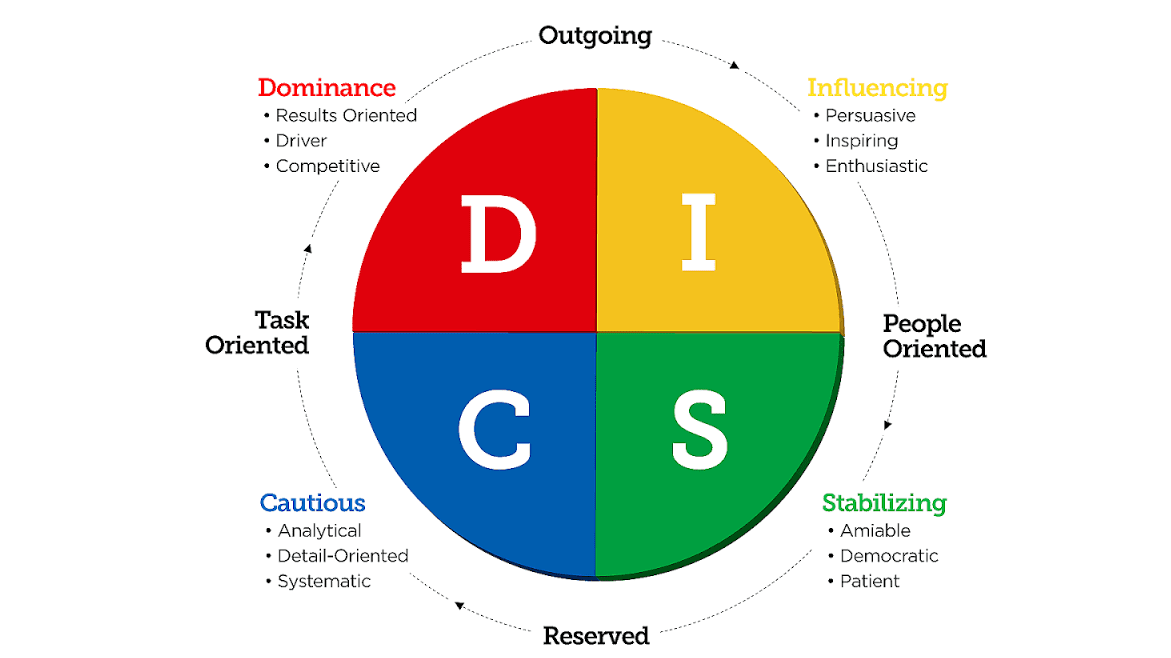

The DISC Test originated with William Moulton Marston in the 1920s and was later adapted into a workplace assessment tool. It divides people into 4 styles: Dominance, Influence, Steadiness, and Conscientiousness. Unlike the MBTI or the Enneagram, DISC focuses on observable behaviour, especially in professional settings, which explains its widespread use in leadership programs, recruitment, and team-building.

Managers appreciate it because it provides simple, actionable insights into how people communicate and collaborate. However, psychologists caution that DISC shares the same weaknesses as MBTI: limited predictive validity and a tendency to oversimplify individuals into categories that may reinforce stereotypes.

Eysenck Personality Test

The Eysenck Personality Test was developed in the 1960s by psychologist Hans Eysenck to measure three broad traits: Extraversion, Neuroticism, and later Psychoticism. Unlike popular test tools, it was rooted in psychophysiology — the study of how mental states are linked to bodily responses, such as brain activity and arousal.

This scientific grounding made it influential in shaping modern models, such as the Big Five. Critics, however, argue that the psychoticism scale is poorly defined and that the three-factor model misses some of the nuance captured by newer frameworks. Even so, the test remains a cornerstone in personality research and one of the most academically respected alternatives to more popular but less scientific assessments.

Colour Personality Test

The colour personality test takes simplification even further. Instead of letters or numbers, people are assigned a colour — often red, blue, green, or yellow — meant to capture their communication or working style. Its charm lies in its accessibility: it’s easy to remember and sparks conversation in classrooms and offices. Saying “I’m a yellow” is a playful shortcut that feels more engaging than citing a percentage of extraversion. But experts stress that it has little to no empirical foundation, merely showing that people can associate character traits with a certain colour. Ultimately, this risks reducing human complexity to something closer to a party trick than a scientific assessment.

Other Niche Tests

There are newer and niche versions of personality tests. The IDR personality test positions itself as a modernised, digital update of Theodore Millon’s personality type theory. Testing for the XNXP personality type test has gone viral on TikTok and Reddit. In practice, XNXP is not a new framework at all but simply a remix of the Myers-Briggs Test, focusing on one slice of its 16 personality types — those individuals who score highly on intuitive and perceiving scales (ENFP, ENTP, INFP, and INTP). This highlights how these personality types are curious and innovative. These newer tests reflect the same hunger for identity and self-categorisation that has kept personal quizzes alive for decades. Like most internet-native formats, they are designed more for engagement than scientific validity.

What Will Personality Tests of the Future Look Like?

For most of the 20th century, understanding personality meant filling out a questionnaire. But science is moving past checkboxes. A recent Frontiers in Psychology review shows how researchers are developing new, more dynamic ways of building an insights personality test that captures how people actually live and behave.

Body and behaviour

Studies suggest that physical traits, such as body shape and facial features, can be linked to Big Five personality traits, including extraversion and conscientiousness. Even gaming style has been tested: how quickly you unlock levels or whether you explore vs. optimise can correlate with the 5 Traits model. Eye-tracking experiments also demonstrate that unconscious responses to visual stimuli accurately predict traits.

Language analysis

The words people use on Facebook, Twitter, or LinkedIn can reveal their personality with as much precision as a survey. Algorithms trained on open-vocabulary language analysis or professional profile cues have been able to construct personality profiles that are closely aligned with traditional measures.

Digital footprints

The boldest advances come from AI and machine learning. Computer models analysing personal digital backgrounds — from “likes” to micro-expressions on YouTube — have outperformed friends and family in judging traits, showing stronger accuracy and predictive validity. This emerging field of computational personality analysis suggests that tomorrow’s tests might be passive, running in the background of our digital lives.

Integrated models

Finally, psychologists are experimenting with models that combine traits, goals, personal narratives, and biology. Frameworks like the socio-genomic model show how genes, environments, and lived experiences interact to shape personality traits over time. Instead of assigning a single score, these models aim to capture personality as a dynamic system.

All these methods point to a future where personality testing is less about static labels and more about living profiles — built from behaviour, language, and biology.

A Checklist for Using Personality Tests Wisely

Personality tests can be fun and thought-provoking, but they’re not verdicts carved in stone. Used wisely, they can be a tool for reflection. Here’s a checklist to keep in mind:

✔ Use them as mirrors, not cages. Let the results highlight patterns in how you think, feel, and act, but don’t mistake them for destiny. Psychologists stress that self-report tools are best seen as starting points for self-reflection rather than final labels.

✔ Distinguish entertainment and evidence. Buzzfeed-style quizzes or colour-based formats are playful, but they lack validation. Tools like the Big Five and Eysenck’s scales show more reliability and predictive power. Keep in mind that unvalidated online quizzes risk reinforcing stereotypes rather than offering real insights.

✔ Watch out for data risks. Online quizzes that appear to be harmless personality tests often request personal details that can be used for fraud or identity theft. The FTC warns that criminals can piece together quiz answers to reset accounts and steal sensitive information.

✔ Be open to change. Personality evolves with age and experience. Long-term studies indicate that lots of personal traits, such as conscientiousness, often increase in adulthood. It’s also natural if your test results shift from year to year — context, mood, and life circumstances can all shape how you answer.

✔ Stay curious. The best use of any online test is as a springboard for conversation and self-exploration, not as a final verdict.

The urge to classify personality is essential and ancient. Hippocrates’ 4 humours offered one of the earliest templates for linking bodily states to temperament, a lineage that runs through medieval medicine and into today’s personality types. What changes is not the impulse to categorise, but the tools we use. “Personality science” is moving beyond self-report questionnaires toward models that integrate digital behaviour and even biology. The challenge will be the same as it has been for millennia: to use these systems as lenses for self-understanding rather than cages that confine human complexity.