Introverts, Extroverts, Ambiverts, Otroverts: Mapping the Personality Spectrum

The internet loves a good personality label. From introverts who recharge alone to extroverts who thrive in a crowd, the language of “-verts” has become shorthand for how we see ourselves and others. But the truth is more complex — and new terms like ambivert and otrovert show just how much our cultural imagination is expanding.

A Brief History of Personality Typing

Personality typing didn’t begin as a corporate icebreaker. The concept dates back to Carl Jung in the early 1920s, who observed that some people seemed to turn inward for reflection. In contrast, others oriented themselves outward toward stimulation and social exchange. Carl Jung’s attempt to understand the psyche resulted in his concepts of archetypes that influence how people perceive the world, introversion and extraversion, which were part of a larger system of psychological “functions” that included thinking, feeling, sensing, and intuition. Jung resisted reducing people to simple types, but his work quickly took on a life of its own.

By the 1940s, mother-daughter duo Katharine Briggs and Isabel Briggs Myers transformed Jung’s ideas into a questionnaire designed to guide career choices during wartime. The result — the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) — packaged personality into 16 neat boxes. It was never meant as hard science, but its easy language and self-affirming feedback fueled its rise. Today, the MBTI is a billion-dollar industry, beloved by HR departments and Instagram accounts alike, despite persistent criticism about its scientific validity.

Meanwhile, academic psychology took a different route. Researchers refined trait theory, resulting in the development of the Big Five personality model. Here, extraversion is one of five dimensions: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (sometimes abbreviated to OCEAN), measured as a spectrum. This model remains the gold standard in personality research.

The tension between popular labels and scientific evidence continues. People crave identity markers that feel intuitive, while scientists remind us that human behaviour resists easy boxes. Personality typing sits at the intersection of those desires: a cultural tool for self-understanding, even if it sometimes drifts from empirical ground.

What Are Introverts and Extroverts?

The words introvert and extrovert get thrown around so casually that they almost feel like zodiac signs: shorthand for explaining why you skipped the party or, conversely, why you stayed at the party until 3 a.m. In reality, introverts are not necessarily shy, nor are extroverts automatically loud. An introvert may feel most alive after hours alone, immersed in thought or creative work, while an extrovert may find the same sense of renewal in a buzzing café or team brainstorming session.

These types describe something more fundamental than behaviour: how we manage and replenish our mental resources. Basically, it’s about our “settings”. Brain imaging studies show that extroverts often have stronger activation of reward centres, which may explain why social interaction feels more energising for them. Introverts, by contrast, tend to have more reactive nervous systems, making overstimulation draining rather than invigorating.

Beyond the Binary: Ambiverts, Omniverts, and Otroverts

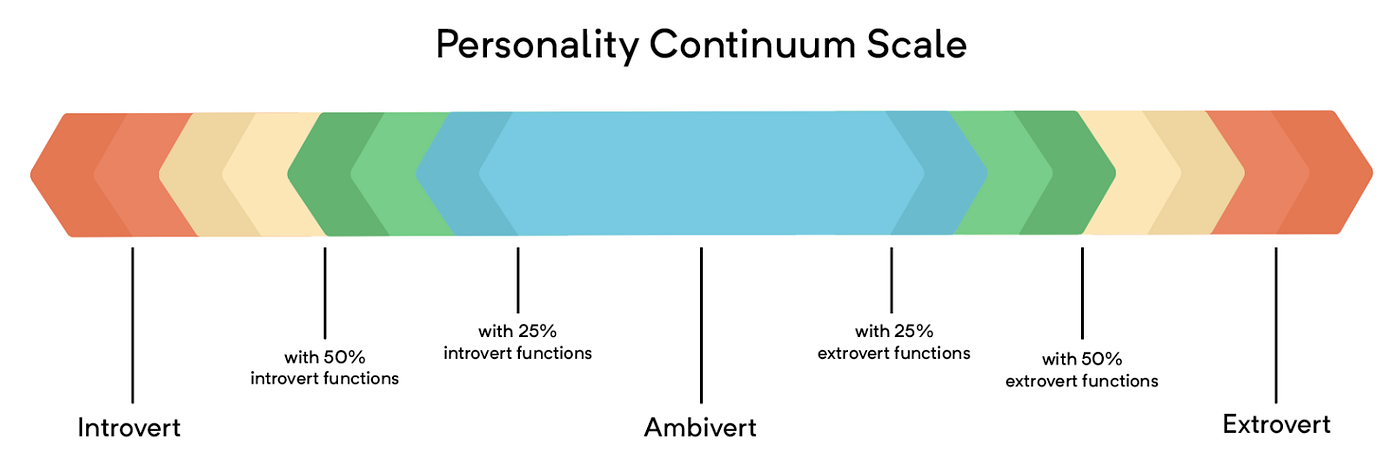

For much of the 20th century, psychology treated introversion and extraversion as a tidy opposition, a personality coin toss. You leaned inward or outward, with only passing acknowledgement that most people existed somewhere in between. But even Jung warned that “there is no such thing as a pure introvert or extrovert.”

Over time, research began to chip away at that binary as well. Studies in the 1970s and 1980s showed that introverts and extroverts differ not only in social habits but also in nervous system reactivity, dopamine pathways, and even brain structure. By the time the Big Five model took hold in the 1990s, extraversion had become less of a type and more of a measurable trait — one point on a spectrum rather than a fixed identity.

Yet science wasn’t the only force reshaping the conversation. Culture demanded a new vocabulary for the messy middle. The term “ambivert” found rare validation in research when Wharton psychologist Adam Grant linked it to advantages in sales and persuasion. Other, less formal labels — such as omnivert, centrovert, and otrovert — emerged from online and media discourse, capturing lived experiences that didn’t fit neatly into earlier models.

Psychiatrist Rami Kaminski explores the concept of otroversion in his book, The Gift of Not Belonging. He describes otroverts as people who live in a constant state of “outsider inside” — welcome in groups but never feeling they truly belong. Unlike introverts, who retreat into their inner world, otroverts remain hyper-attuned to others, often overwhelmed by the constant flux of social cues. They prefer one-on-one connections over group rituals, thrive when they have a clear role, and practice what Kaminski calls the art of the “Irish exit” — slipping quietly out of a social event without announcing their departure. Rather than a flaw to be corrected, he frames otroversion as a distinct cognitive style — a way of moving through the world that carries both burdens and unique strengths.

While psychologists may roll their eyes at the lack of rigour, these words reveal something essential: people want tools to name their fluidity, their shifts across context and time.

The Personality Spectrum at a Glance

If the old dichotomy was a line, today’s personality spectrum looks more like a constellation. It’s not about finding your single dot on a ruler, but about tracing patterns across contexts. Here’s how the major “-vert” identities play out.

- Introverts gravitate toward environments with low stimulation. They’re not anti-social; they simply conserve energy by focusing inward, preferring one-on-one conversations or creative pursuits over crowded events.

- Extroverts thrive in external stimulation. They draw energy from people, novelty, and shared experiences. Research has linked higher extraversion scores to increased dopamine activity, which may explain their appetite for social interaction.

- Ambiverts live in the middle, bending toward one side or the other depending on the situation. They often thrive in modern workplaces, where both collaboration and independent work are required.

- Omniverts are less predictable: they might dominate a social event one day and vanish into solitude the next. While not formally studied, the concept resonates with people who feel they live at both extremes.

- Centroverts are less formally studied, however, they are described to embody moderation, rarely pulled firmly to either pole. Their neutrality may sound unremarkable, but it reflects stability and ability to collaborate that’s undervalued in a culture obsessed with extremes.

- Otroverts — the cultural newcomer — don’t fit neatly on the introvert–extrovert axis at all. Their identity is relational, shaped by the presence and feedback of others. For them, the self isn’t fixed but emerges in the social fabric.

This spectrum isn’t definitive, but it reveals a shift: personality is not fixed but rather a fluid process. Evidence shows that people may mellow as they get older — and new findings suggest the pandemic itself may have reshaped personality, at least for a time.

Why Personality Labels Matter

Why does it feel so satisfying to say, “I’m an introvert,” or “I’m an ambivert”? Part of the answer lies in psychology itself: humans are meaning-making creatures. Labels give us a narrative framework, a way to explain why we decline an invitation, prefer email over phone calls, or thrive in fast-paced environments. They’re shorthand not just for who we are, but for how we want to be understood.

But there’s also a cultural hunger at play. In an era defined by self-optimisation and identity politics, personality labels function like micro-brands. They’re signals in the social marketplace — introvert memes, extrovert networking tips, ambivert career hacks. This doesn’t make them trivial. Research suggests that believing in a coherent identity, even if simplified, can reduce stress and help people regulate behaviour. It offers clarity in a world of overwhelming choice.

The Limits of Personality Typing

Personality tests promise clarity: a neat profile, a set of letters, a label that explains why you are the way you are. It’s no wonder they’ve flourished in workplaces, dating apps, and TikTok feeds. But psychologists have long warned that typing systems can be more seductive than scientific.

Labels can harden into stereotypes, flattening the complexity of lived experience. They can excuse behaviour (“I ghost because I’m an introvert”) or stigmatise differences (“Extroverts are shallow”). The scientific consensus suggests that the Big Five model provides a more nuanced and reliable framework: we are spectrums, not segments.

New personality terms aren’t likely to stop at ambiverts or otroverts. Tomorrow, Gen Z might crown the flexiverts — personalities who bend and stretch depending on the vibe of the room. Or maybe scrollverts, who reveal their true selves only online. The point is, new labels will keep bubbling up, half-serious and half-satirical. And that’s part of the fun: these inventions remind us that personality isn’t static, it’s a living story we keep rewriting together.

The real innovation lies in holding both truths: using labels as tools for self-reflection and connection, while acknowledging that personality is a dynamic entity, shaped as much by culture and context as by biology.