Reading Navigation

The Promise of Ketamine Therapy: A Hope for Treatment-Resistant Depression

Depression is one of the world’s most disabling illnesses, affecting more than 264 million people1 globally — severely limiting quality of life and work productivity. For most, antidepressants and psychotherapy bring relief. But up to 30% of patients2 do not respond to standard treatments like antidepressants — this condition is known as treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Patients often face long-lasting symptoms and frequent relapses despite repeated treatment attempts.

Against this bleak backdrop, ketamine has emerged as a new hope. Once known primarily as an anaesthetic — and later as the club drug “Special K” — it is now the subject of nearly 50 randomised clinical trials worldwide and growing clinical adoption in Europe and North America. Unlike conventional antidepressants, which may take weeks to work, ketamine can lift mood within hours. Clinics offering ketamine therapy are expanding rapidly, raising both optimism and questions about safety, long-term effects, and access.

What Is Treatment-Resistant Depression

Most people with depression eventually improve with standard treatments such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs, a type of antidepressant) or psychotherapy. But for a significant minority, these approaches fall short. Treatment-resistant depression, or simply TRD, is typically defined3 as a lack of meaningful improvement after trying at least two different antidepressants at adequate doses and duration.

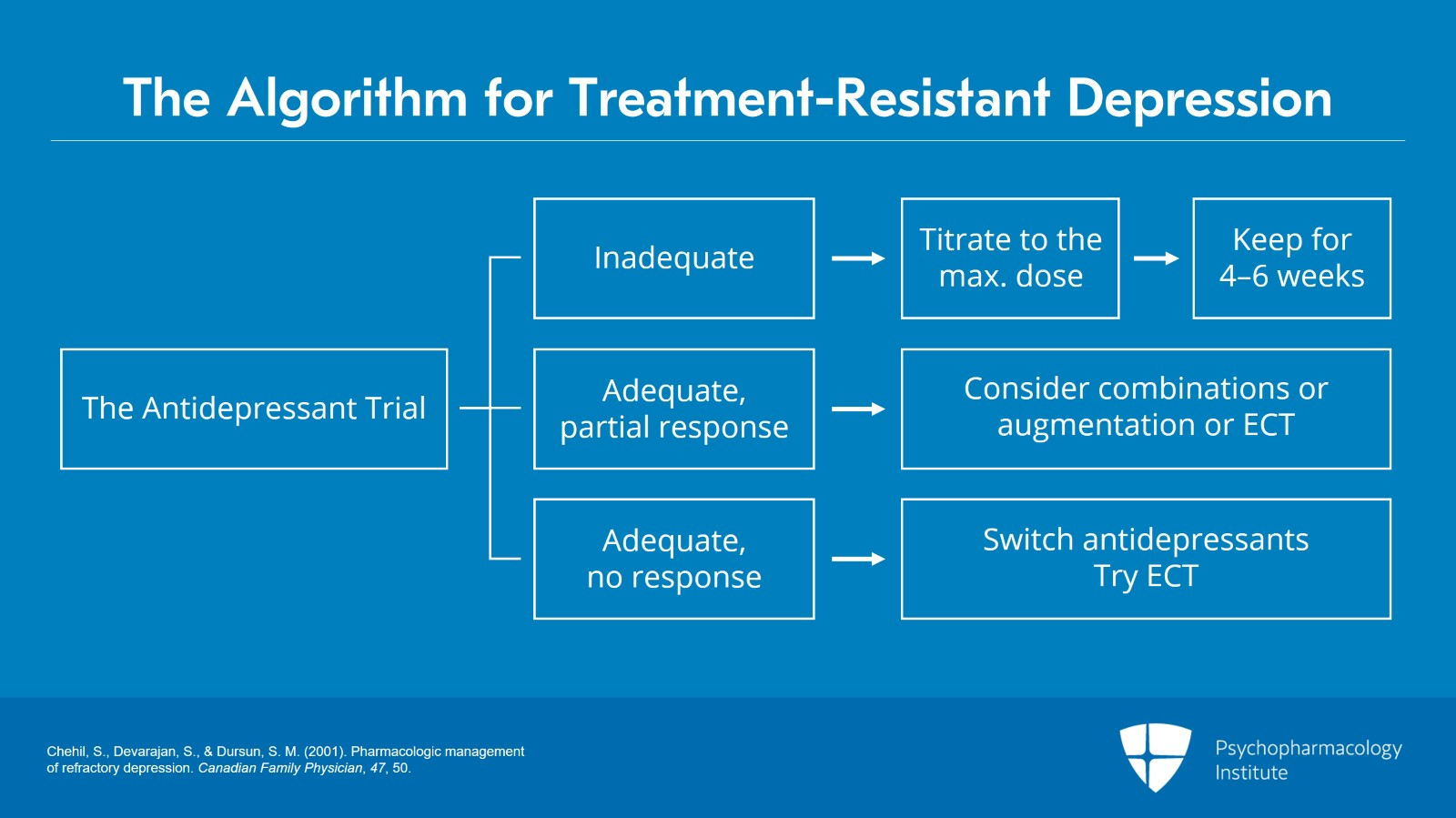

Before therapists label depression as treatment-resistant, patients typically progress through a structured sequence of treatment steps. First, a conventional antidepressant, such as Sertraline (Zoloft) or Fluoxetine (Prozac), is prescribed for at least 1 month. If it provides only partial or no relief, doctors usually try one of two approaches: switch to a different antidepressant or add a second medication to enhance the first. If the initial antidepressant at the standard dose does not provide adequate response, doctors may first titrate to the maximum tolerated dose.

If two different antidepressants fail to help, patients typically progress to more intensive treatments like electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or other advanced therapies.

TRD is more common than it might seem: nearly 30% of patients2 with major depressive disorder (MDD) fall into this category. These individuals often cycle through medications for months or years, experiencing only partial or temporary relief. The consequences extend beyond mood. People with TRD usually report2 a persistently low mood, a loss of interest or pleasure in daily activities, constant fatigue, disturbed sleep, changes in appetite, difficulties with concentration, and an ongoing sense of guilt or hopelessness. These symptoms tend to be more severe than in typical cases of depression, and they interfere deeply with work, relationships, and overall quality of life.

Another challenge is time. Traditional antidepressants usually require 4 to 12 weeks3 before their effects become noticeable, and even then, many patients do not reach remission. During this waiting period, symptoms may worsen, creating frustration and hopelessness. Because of this, researchers and clinicians have been searching for therapies3 that can work more quickly and more reliably, which is where ketamine entered the conversation.

Antidepressants VS Ketamine for Depression

The antidepressant potential of ketamine was first noticed4 in small clinical trials in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when patients who had failed conventional medications showed rapid mood improvements within hours of an infusion. Unlike standard antidepressants, which usually require weeks of continuous use to build up their effect, ketamine’s action is almost immediate and follows an entirely different biological pathway.

But how does ketamine differ from traditional therapy?

- Rapid onset of action. While antidepressants like SSRIs and SNRIs typically take 4–12 weeks to show benefits, ketamine can ease depressive symptoms within hours4 of administration.

- Different molecular targets. Most antidepressants work by altering monoamine levels (serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine). Ketamine instead modulates4 the glutamate system by blocking NMDA receptors and enhancing the activity of AMPA receptors. That means ketamine helps the brain form connections between nerve cells much faster than it usually does.

- Neuroplasticity and brain rewiring. Evidence from clinical studies shows5 that ketamine promotes new synaptic connections in mood-related regions, such as the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, helping sustain its antidepressant effect even after the drug is metabolised.

- Lasting effects. Even though ketamine leaves the body within hours, it activates processes like BDNF — a protein change that helps brain cells form new connections, and mTOR — a pathway that supports cell growth and repair. Together, these changes may explain why mood improvements can last for days or even weeks after treatment.

- Circuit-level changes. Neuroimaging research suggests6 that ketamine helps restore disrupted connectivity in networks regulating mood, such as between the prefrontal cortex and limbic regions of the brain. Standard antidepressants also affect these circuits, but typically more gradually and with different connectivity signatures.

- Response in TRD. Ketamine works in some patients who have failed multiple rounds of traditional antidepressants — meta-analyses report response rates around 50–70%.

In 2019, the FDA approved intranasal esketamine (Spravato) for treatment-resistant depression, marking the first new rapid-acting antidepressant pathway in decades. This approval not only validated ketamine’s antidepressant potential but also opened the door for broader clinical acceptance and further research into ketamine infusions, maintenance strategies, and next-generation glutamate-based therapies.

What the Research Reveals About Ketamine’s Impact

Over the past two decades, ketamine has moved to large randomised controlled trials. The data highlight its unusually rapid action and lasting benefits for patients with treatment-resistant depression. Here’s a summary of key findings from primary studies:

- Already in 1 hour1, the first measurable improvements in depression and suicidal thoughts appear.

- In 1–3 days, marked symptom reduction is reported7 in most patients.

- Nearly 64% of patients show8 a clinical response in 1 week.

- Repeated infusions help sustain9 remission for 2 to 4 weeks, with longitudinal studies showing extended remission up to 9-12 months (e.g., 79% at 9 months with maintenance and antidepressants).

- A meta-analysis of 79 studies (n ≈ 2,665) reveals response rates of ~45% and remission rates of ~30%.

- Monthly infusions have stabilised10 patients in Norwegian clinics, with more than 350 treated so far.

- Some trials have shown11 that ketamine is comparable to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), with fewer cognitive side effects.

- Reduction in suicidal ideation within one day and for up to one week.

In short, clinical research paints a consistent picture: for many patients who have exhausted standard options, ketamine therapy can deliver rapid relief and sustained improvement. Its ability to stabilise some patients over months places it at the centre of a shift in how depression is managed today.

Ketamine Treatment for Depression in Practice

A typical course of ketamine therapy often starts with an induction phase: 6 infusions or sessions over 2 to 3 weeks. If patients respond, they may proceed13 to maintenance treatment, where sessions are spaced out weekly or monthly to help sustain the benefits.

Ketamine therapy can take different forms, but the goal is always the same: to deliver the drug safely under medical supervision and track its effects on depression symptoms.

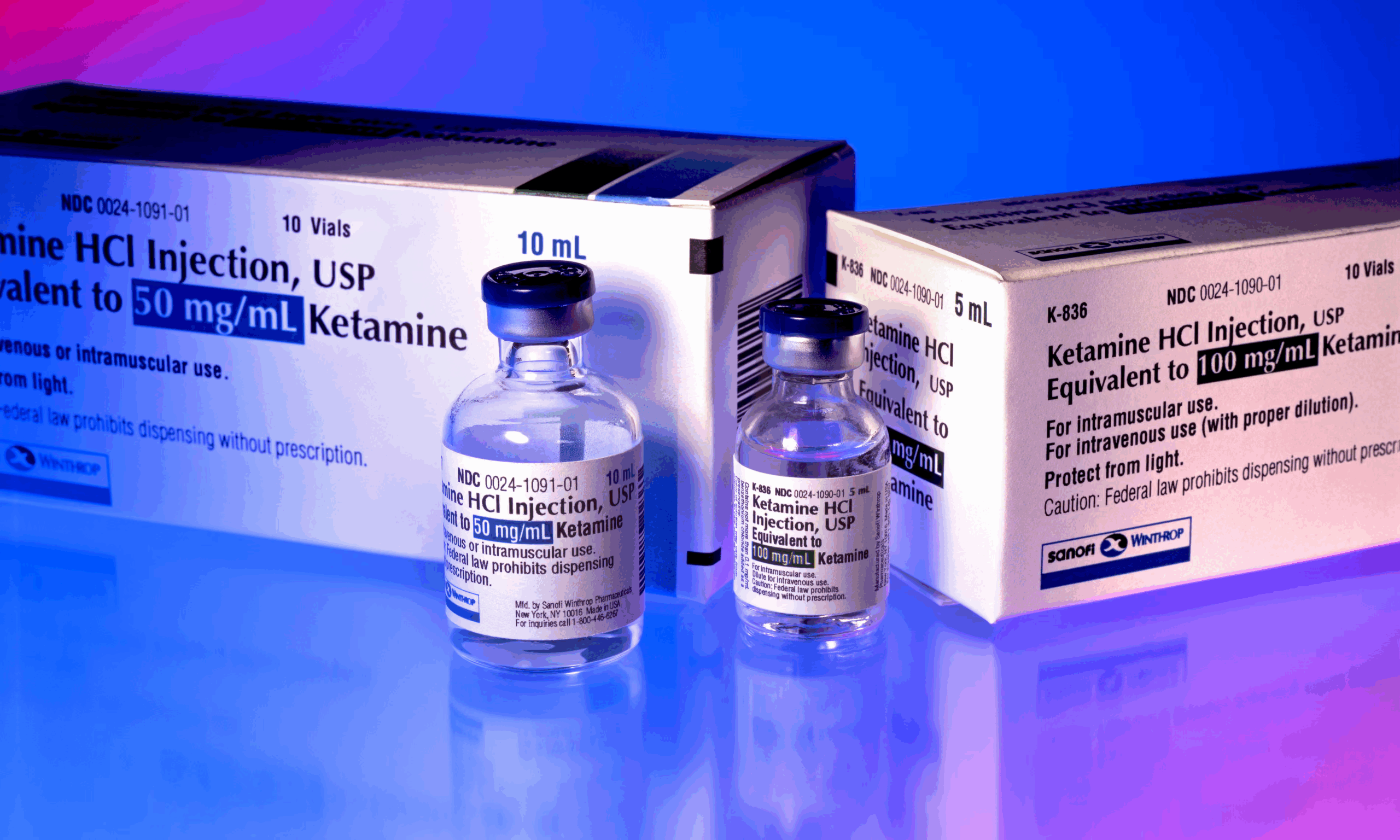

- Intravenous infusion (IV) is the most studied method. Patients receive ketamine through a slow drip, usually 0.5 mg/kg over 40 minutes, while sitting or lying in a comfortable clinical setting. Throughout a session, therapists monitor vital signs such as blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen levels. Many patients begin to notice changes in mood within an hour.

- Intranasal spray (esketamine) was recently approved for treatment-resistant depression. It’s taken not at home, but under supervision in a certified clinic: patients spray the substance themselves, then remain under observation for at least 2 hours while staff monitor for side effects such as dizziness or dissociation.

- Other routes — such as intramuscular injection, oral lozenges, or sublingual formulations — are used in some clinics, but research data on these options are limited. They tend to have3 less predictable absorption compared to IV or nasal spray.

The therapy environment is designed to be calm and supportive. Many clinics provide reclining chairs, eye masks, and music to reduce anxiety during dissociative effects. Because ketamine works best when combined with other treatments, it’s often paired with psychotherapy or ongoing antidepressant medication to strengthen long-term outcomes.

Beyond Ketamine: Comparing Therapy Options

Ketamine is not the only option for patients with treatment-resistant depression. To see its place in modern psychiatry, it’s worth comparing it with other advanced therapies:

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

ECT has long been considered the most effective treatment for severe, hospital-level depression. Large trials, such as the ELEKT-D study, show that ECT often achieves16 higher response rates than ketamine in inpatients, particularly when psychotic symptoms are present. At the same time, ketamine tends to preserve17 cognitive function better, as ECT is associated with memory impairment and other mental side effects. This makes ketamine a more tolerable option.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS)

TMS uses magnetic fields18 to stimulate mood-related brain regions. It is non-invasive, does not require anaesthesia, and avoids the dissociation linked to ketamine. The main limitation is that response rates are typically lower compared to ketamine or ECT. Researchers are now exploring18 whether pairing TMS with ketamine might extend the antidepressant effect.

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS)

This therapy involves surgically implanting a device that delivers mild electrical pulses to the vagus nerve in the neck. VNS is FDA-approved for chronic depression and has demonstrated19 improvements in long-term trials, though benefits often take months to appear. Long-term studies indicate20 that patients who respond can maintain their improvement for years, making VNS a durable yet invasive option. Compared to ketamine’s rapid onset, VNS is slow-acting but potentially more stabilising in the long run.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS)

DBS is still experimental for depression, requiring neurosurgical implantation of electrodes into targeted brain regions. Meta-analyses report21 response and remission rates ranging from ~50–60%, though results remain mixed. Recent high-quality trials, however, show that in carefully selected patients, DBS can produce long-lasting remission, with some studies reporting up to 70% remission22 within 6 months. In contrast, ketamine is non-surgical and fast-acting, though with less certainty about long-term outcomes.

Discover Your Path to Recovery From Depression

Each treatment has its own balance of effectiveness, invasiveness, cost, and side effects.

Ketamine has fundamentally changed what is possible for patients with TRD. Unlike traditional antidepressants that take weeks to work, ketamine delivers rapid relief within hours — offering hope to those who have exhausted standard options.

Beyond ketamine itself, this breakthrough has opened doors to next-generation compounds like arketamine and hydroxynorketamine, as well as to more personalised treatment strategies guided by biomarkers23 and brain imaging. For the millions struggling with TRD, ketamine represents a genuine turning point: proof that effective, rapid-acting treatment is achievable, and a beacon for the future of depression care.