Why We’re Tired All the Time? The Science of Chronic Fatigue

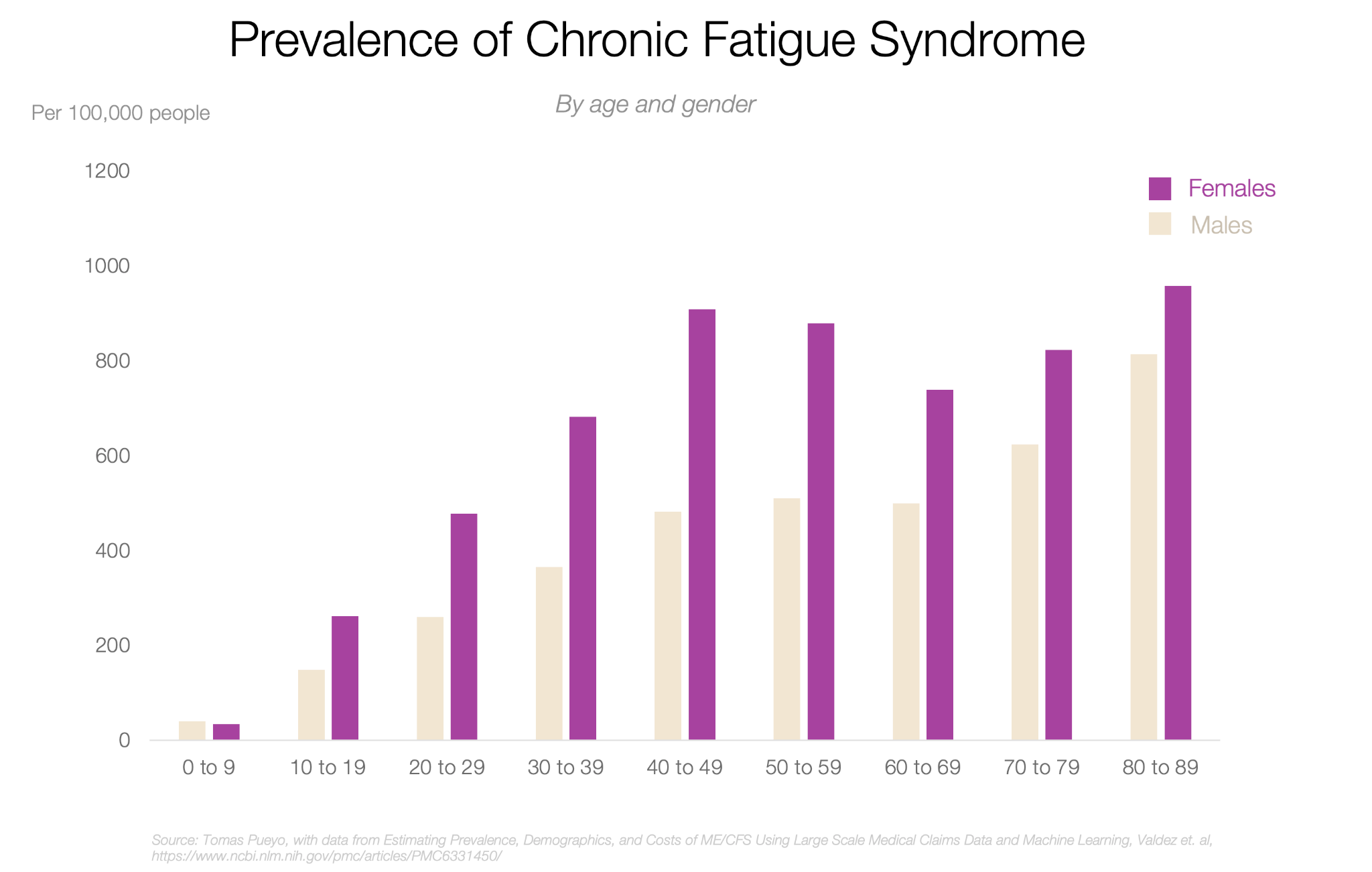

We live in an age where being tired all the time has become both a meme and a medical reality. Surveys suggest that up to 15% of adults worldwide experience chronic fatigue, with women affected more often than men.

For decades, this exhaustion was brushed off as psychological — physical symptoms caused or exacerbated by the mind. But new science is rewriting the story. From large-scale genetic studies identifying biological signals behind myalgic encephalomyelitis (also known as chronic fatigue syndrome, ME/CFS) to brain imaging that links fatigue with changes in the brainstem and immune system, researchers are showing that fatigue is not just in our heads. It’s a complex biological condition that affects millions, and understanding it may be the key to lifting one of modern life’s most invisible burdens. And if you’re not exhausted yet, let’s unpack the science of fatigue.

What Is Fatigue, Basically?

At its simplest, fatigue means more than just being “a bit tired.” While tiredness is a standard signal that the body needs rest, fatigue is a deeper, more persistent state where energy, focus, and motivation feel drained. Therapists describe it as both a physical and psychological condition, characterised by a mix of slowed reaction times, muscle weakness, and the overwhelming sensation that no amount of rest fully restores one’s energy.

The difference between ordinary tiredness and chronic fatigue is crucial. Short-term fatigue after a late night or an intense workout usually resolves with sleep and recovery. Chronic fatigue, by contrast, lasts for weeks or months and often has no apparent cause. It can be linked to infections, immune system changes, or long-term stress, and in severe cases, it develops into myalgic encephalomyelitis / chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

Fatigue symptoms can range from constant sleepiness and muscle heaviness to headaches, irritability, and memory lapses. Researchers stress that there is no single trigger — fatigue causes are multi-layered, from disrupted circadian rhythms to immune dysfunction or sustained emotional strain.

Common Types of Fatigue

Fatigue is not one-size-fits-all — it can be physical, mental, or a mix of both. Sometimes it appears in your muscles after exercise, and at other times, it manifests in your mind after hours of decision-making or caring for others.

Muscle fatigue

When muscles are pushed beyond their capacity — during exercise, illness, or even prolonged sitting — they lose the ability to generate force. It is muscle fatigue: the burning sensation in your legs after sprinting, or the weakness in your arms after lifting weights. It’s caused by biochemical changes inside muscle fibres, such as energy depletion and lactic acid build-up.

Decision fatigue

Our brains also tire. Every choice we make — from what to wear in the morning to how to handle a work crisis — consumes mental resources. Over time, this leads to decision fatigue, where making even simple decisions feels overwhelming. Judges, doctors, and managers are known to make poorer decisions late in the day because of this hidden cognitive drain.

Compassion fatigue

Emotional energy can also run dry. Nurses, therapists, and caregivers often describe compassion fatigue — a numbness that sets in after prolonged exposure to others’ suffering. Unlike ordinary stress, it is rooted in empathy: the cost of caring deeply, day after day.

Adrenal Fatigue — Myth or Not?

Some wellness practitioners use the term “adrenal fatigue” to describe constant fatigue, brain fog, and low energy supposedly caused by “burned-out” adrenal glands after chronic stress. However, mainstream medicine does not recognise adrenal fatigue as a real diagnosis — studies show that adrenal function usually remains normal in such patients. What people often label in this way may reflect stress-related disruptions in sleep and hormone levels.

The multidimensional nature of fatigue highlights why scientists are increasingly viewing it not as a single condition, but as a complex web of biological, psychological, and social processes. This broader view also helps explain why, in its most severe and persistent form, fatigue develops into chronic fatigue syndrome — a mental condition that goes far beyond ordinary tiredness.

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Explained

When fatigue persists week after week, it may signal more than just being “tired.” Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) is a distinct medical condition that affects millions worldwide. Yet despite its prevalence, it is still widely misunderstood — often minimised as laziness or “just stress.”

Symptoms and Diagnosis

The core features of ME/CFS go far beyond ordinary exhaustion. Patients report:

- Extreme fatigue that does not improve with rest.

- Post-exertional malaise (PEM) — a dramatic worsening of symptoms after even mild physical or mental effort.

- Cognitive dysfunction, often called “brain fog”, — affects memory, focus, and processing speed.

- Chronic pain, sleep disturbances, dizziness, and immune sensitivities.

There is no single test for chronic fatigue syndrome. Diagnosis remains a process of exclusion: doctors rule out other illnesses that might explain the symptoms. That’s why the difference between constant fatigue from stress and a medical syndrome like ME/CFS is critical — the latter involves specific disabling symptoms with biological causes.

From “Psychosomatic” to Biological Evidence

For decades, ME/CFS was dismissed as a psychosomatic disorder, often stigmatised as being “all in the head”. This stigma not only harmed patients but also delayed research funding and treatment options.

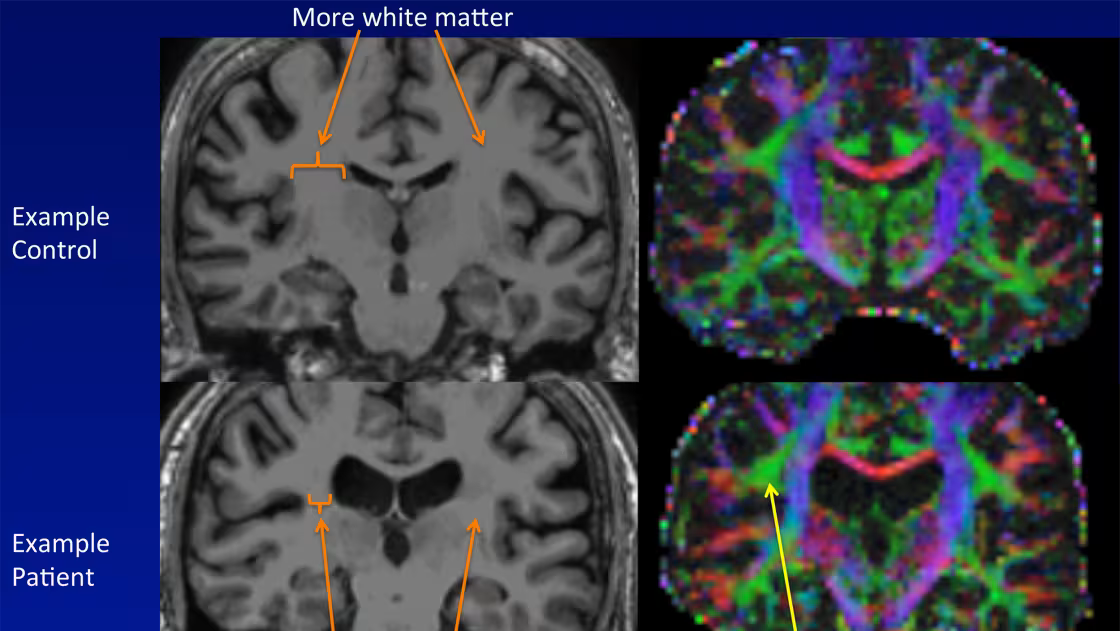

That narrative is now changing. New studies have identified immune system abnormalities, neuroinflammation, and metabolic dysfunctions in patients. Large-scale projects like the DecodeME genetic study are uncovering potential genetic links. Meanwhile, neuroimaging research shows measurable changes in brain connectivity and blood flow. Immune pathway disruptions and post-viral fatigue mechanisms also place ME/CFS in the same scientific conversation as Long COVID, which has drawn fresh attention — and urgency — to the condition in post-pandemic years.

The Biology of Exhaustion

Fatigue is not just “in the mind” — it emerges from a complex interplay between the brain, muscles, and immune system. Scientists distinguish between central fatigue, where the nervous system alters how signals are processed, and peripheral fatigue, which occurs when muscles themselves can no longer sustain force. This dual view helps explain why exhaustion can feel both physical and mental at once.

Brain and Nervous System

Central fatigue refers to the role of the brain and spinal cord in contributing to tiredness. Instead of muscles simply “running out of energy,” signals from the brain regulate how much effort we feel able to produce. Neuroimaging studies have demonstrated that fatigue is associated with altered activity in brainstem and cortical networks involved in attention and motivation. This is why mental effort — such as exams, long meetings, and endless decisions — can feel just as draining as physical exertion.

Immune System and Post-Viral Fatigue

Infections can trigger long-term exhaustion. Many people with chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) report their symptoms began after a viral illness, a pattern echoed in recent cases of Long COVID. Research suggests that immune dysfunction, chronic inflammation, and abnormal cytokine signalling (faulty immune messaging) may all contribute to sustained fatigue. Post-viral fatigue is a well-documented pathway: studies show that more than 50% of people with Long Covid also have chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

Genetic Clues

Large-scale genetic studies are beginning to unravel the molecular underpinnings of fatigue. The DecodeME genome-wide association study — the largest of its kind, with over 15,000 participants — identified 8 genetic signals linked to ME/CFS: genes involved in immune responses (e.g., OLFM4, ZNFX1) and pain processing (CA10). While these findings explain only part of the risk, they provide strong validation that ME/CFS is a biological condition.

Coping With Fatigue: Clinical Care + Practical Tips

Managing fatigue involves drawing a clear line between chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and ordinary tiredness. ME/CFS requires clinical management — pacing, symptom-oriented therapy, and ongoing research into immune and neurological pathways. Everyday fatigue, by contrast, can often be improved with practical lifestyle steps: better sleep hygiene, balanced activity, stress reduction, or nutritional adjustments.

CFS Clinical Approaches

CFS treatments focus on symptom management. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and pacing strategies have been used to help patients cope with daily limitations. The role of exercise therapy remains debated: while graded exercise therapy (GET) was once recommended, many patients report worsening symptoms, and recent guidelines advise caution.

Research into biological mechanisms is opening new doors. Studies suggest immune dysregulation and neurological changes may be targets for future treatments. Several drug candidates are in early-stage trials, but none have been approved by the FDA yet. Integrative approaches, including physiotherapy, pain management, and nutritional support, are often part of multidisciplinary care.

Daily Practical Checklist

For those experiencing everyday tiredness, practical steps can make a difference:

- Sleep hygiene: keep a consistent sleep schedule, reduce blue light exposure before bed, and prioritise restorative rest.

- Balanced activity: alternate periods of movement and rest, avoiding extremes of overexertion or complete inactivity.

- Nutrition: regular meals, hydration, and avoiding heavy late-night eating can stabilise energy levels.

- Micro-breaks: short pauses during mental work help reduce decision fatigue and improve focus.

- Stress reduction: mindfulness, breathing exercises, or yoga can lower perceived fatigue and improve resilience.

- Integrative care: techniques such as deep breathing or gentle physical therapy for deconditioning are increasingly studied.

Can We Ever Stop Being So Tired?

If fatigue has biological or genetic roots, does that mean it’s inevitable? Science tells a different story. While ME/CFS is deeply rooted in biology and still lacks a cure, research into genetics, immune dysfunction, and brain pathways is pushing the field forward. At the same time, the exhaustion so many of us feel is also a symptom of the times we live in: long workdays, decision overload, and the aftershocks of a pandemic. That doesn’t mean we’re doomed to stay tired. It means fatigue is both a medical condition and a cultural signal.

The hopeful horizon? With every study, we move closer to understanding the biology of exhaustion and finding ways to ease it. Fatigue doesn’t define us; it reminds us that we are human, and that care — personal, medical, and societal — can change the story.

FAQ

- Why am I tired all the time?

Feeling tired occasionally, whether physically or psychologically, is normal. But constant fatigue can signal deeper issues — from poor sleep and stress to conditions like anaemia or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

- How do I know if it’s just stress or chronic fatigue syndrome?

Stress-related tiredness usually improves with rest and lifestyle changes. CFS is different: extreme fatigue, brain fog, and chronic pain that persist for months.

- What are the first warning signs of chronic fatigue?

Early red flags include constant exhaustion that doesn’t improve with sleep, sensitivity to even mild exertion, and recurring aches or dizziness. If these symptoms last longer than six months, doctors may consider ME/CFS.

- Does COVID cause chronic fatigue?

Yes, in many cases. Studies show that over half of long COVID patients meet the criteria for ME/CFS, suggesting a strong link between viral infections and post-viral fatigue.

- Is there a test for chronic fatigue syndrome?

No single test exists — doctors diagnose ME/CFS by ruling out other conditions.

- What actually helps with everyday tiredness?

For most people, everyday fatigue improves with basics: regular sleep, balanced activity, hydration, nutrition, and short micro-breaks during work. Stress-reduction techniques, such as mindfulness, yoga, or breathing exercises, can also help recharge mental energy.