When Body Image Turns Toxic: Eating Disorders in a Digital World

- This article explores how social media–driven body ideals and wellness culture contribute to the rise of disordered eating patterns, including orthorexia and body dysmorphic disorder (BDD).

- By integrating contemporary research and lived experience reports, it offers a comprehensive view of how digital comparison culture, often proliferated by social media, can transform the perception of body image into a source of psychological distress.

Scroll through Instagram or TikTok today, and you’ll find endless filters, “body transformation” reels, and fitness challenges promising the perfect look. At the same time, demand for cosmetic surgery continues to climb worldwide. Against this backdrop, concerns about body image have become almost universal — but for some, they can tip into serious mental health struggles.

Research shows that 20–40% of women and 10–30% of men report dissatisfaction with their bodies, and up to 3% of adults live with body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) — a condition defined by obsessive worries over perceived flaws in appearance. Among people seeking cosmetic surgery, the rates may soar to 1 in 4. These numbers aren’t just about vanity; they reveal how deeply our relationship with body image shapes self-esteem, anxiety, depression, and eating disorders.

Understanding body image and BDD isn’t about explaining why people diet or chase aesthetic ideals. It’s about uncovering how cultural messages, media pressures, and personal experiences combine to affect mental health — sometimes with life-altering consequences.

What Is Body Image?

Body image is the mental picture we carry of our own body — how it looks, how it feels, and how much it seems to “fit” social ideals. It’s not only appearance but also our emotions: pride, shame, or neutrality toward the body. Everyday insecurities (disliking a photo angle, choosing what to wear best) are common and usually fleeting. A clinical disturbance begins when dissatisfaction dominates self-worth and disrupts daily life. That’s why body image difficulties are closely linked with higher levels of anxiety, depression, and disordered eating symptoms.

“I had always been underweight as a child, and then puberty came, bringing changes I wasn’t ready for. My mother told me to stop eating and to exercise more. Friends called me chubby. Strangers would comment on my look, calling me ugly. Bullying was everywhere, unrelenting, and it shaped the way I saw myself,”

recalls a Reddit user in her story for States of Mind.

Researchers highlight three layers of body image:

- Intrapersonal — the internal dialogue about one’s body and its role in self-esteem.

- Interpersonal — the influence of peers, family, and partners through comments, comparison, or criticism.

- Systemic — cultural and media forces that set shifting standards of beauty and strength.

It’s crucial to distinguish this concept from body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). Body image concerns can be intense but still flexible. In BDD, worries about perceived flaws become obsessive and fixed, often leading to compulsive behaviours and severe distress.

What Is Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD)?

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), in contrast, is a psychiatric condition where a person becomes excessively preoccupied with perceived flaws in their appearance — flaws that are either minor or invisible to others. Unlike ordinary insecurities, these concerns are persistent, overwhelming, and often life-disrupting.

Common Symptoms

People with BDD typically experience:

- Mirror checking or, conversely, avoiding mirrors altogether

- Constantly comparing yourself with others

- Camouflage behaviours, such as heavy makeup, hats, or clothing to hide the “defect”

- Skin-picking or grooming rituals aimed at fixing perceived imperfections

- Seeing many healthcare providers about your appearance

- Social withdrawal — avoidance of work, school, or social relationships

- Suicidal thoughts, feeling anxious, depressed, and ashamed

Causes and Comorbidity

The disorder arises from a mix of biology and environment. Twin studies suggest a heritability of approximately 40%, indicating a significant genetic component. Experiences of bullying, childhood trauma, or critical parenting increase vulnerability, while cultural ideals and media pressure amplify it.

BDD rarely appears alone. It often overlaps with other psychiatric conditions, including obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), major depression, and eating disorders. This overlap complicates diagnosis: patients may present with symptoms of anxiety, compulsions, or dieting behaviours, while the root problem — distorted perception of their own body — remains hidden.

When Body Image Drives Eating Disorders

Eating disorders (ED) are mental conditions where food, weight, and body shape take a central — and often destructive — role in daily life. The main ED types are:

- Anorexia nervosa — restricting food intake and pursuing extreme thinness, often at the cost of physical health.

- Bulimia nervosa — cycles of binge eating followed by compensatory behaviours like vomiting, laxatives, or excessive exercise.

- Binge eating disorder (BED) — repeated episodes of consuming large amounts of food with a sense of loss of control, usually without purging.

- Orthorexia — an obsessive focus on eating only “healthy foods.” While not officially recognised in the DSM-5, orthorexia can lead to rigid dietary rules and blur the line between wellness and disordered behaviour.

Reflecting on the origins of her eating disorder, a Reddit user describes restricting food as a way to reclaim control:

“I stopped eating because it was the only thing that felt real. It was the only thing I could claim for myself in a world that constantly let me down. I know it doesn’t fix anything, I know it isn’t real control, but it feels like the one thing I can hold onto.”

Across all diagnoses, body dissatisfaction is one of the strongest predictors of disordered eating. Studies consistently show that the more negatively a person evaluates their own body, the greater the risk of developing an eating disorder. Experts emphasise that the foundation of eating disorder treatment is nutritional management, usually paired with evidence-based psychotherapy to address the psychological aspects of the condition.

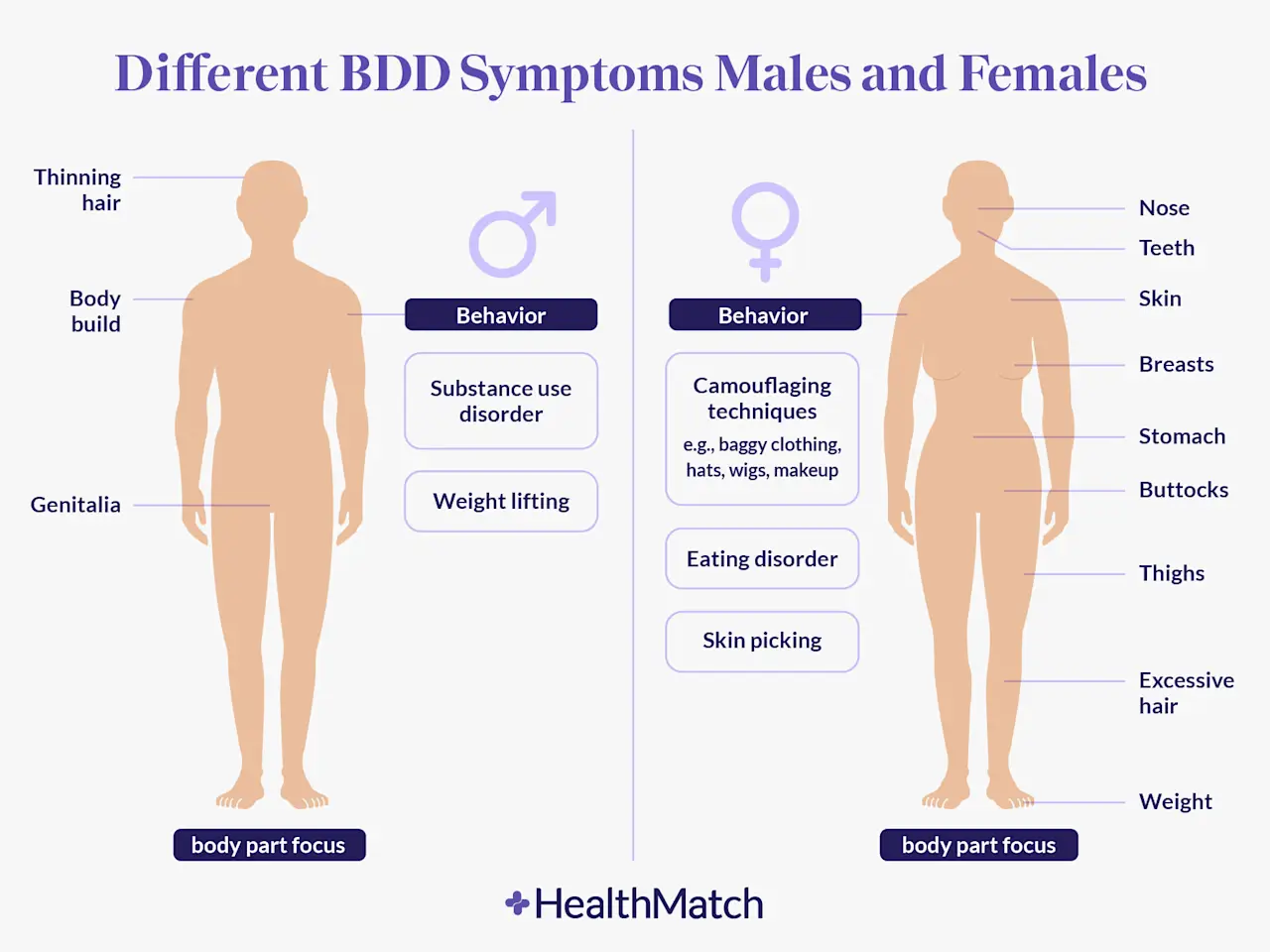

Gender Differences

Body image pressures don’t look the same for everyone. Men with eating disorders are often driven by a desire for muscularity and leanness, framing their behaviours as “fitness goals.” Compulsive exercise and high-protein dieting can mask symptoms and delay diagnosis. Women, on the other hand, face stronger cultural pressure to conform to thin or “slim-thick” ideals, where the body is expected to be both lean and curvy.

Social Media and Body Ideals

Cultivating a positive body image — valuing the body’s functionality and accepting diversity — can buffer against some of the harmful effects of dissatisfaction. Yet it cannot entirely shield people from the pressures that trigger eating disorder symptoms — especially in social media and cultural ideals.

Platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube flood users with filters, #fitspiration content, and curated images that distort what real bodies look like. Instead of showcasing diversity, they reinforce narrow ideals — the lean and muscular male body, or the skinny female figure. Research confirms that frequent exposure to appearance-driven content correlates with higher body dissatisfaction and more severe eating disorder symptoms.

Beyond appearance, they promote “clean eating” and restrictive diets as signs of discipline and self-worth. This constant stream can trigger and reinforce orthorexic behaviors, turning healthy habits into fixation.

Labels like “summer body”, “nike pro”, or “dad bod” reduce complex realities to stereotypes, fueling stigma and anxious comparison. For example, time spent on Instagram is directly linked with lower self-esteem and body satisfaction.

Viewing athletic or “fit” images reduces self-esteem in young adults, especially women. A meta-analysis of appearance-related social media content revealed stronger body comparison and dissatisfaction in pictures compared to neutral or diverse images. And while body-positive content can temporarily improve mood and acceptance, its protective effects remain modest.

For men, these influences often translate into compulsive exercise and restrictive “high-protein” regimens framed as health goals. For women, constant comparison to thin-ideal influencers can intensify cycles of dieting, bingeing, or purging. All Reddit users who shared their stories with States of Mind highlighted the massive influence of social media on their body image:

Female, 20:

“Social media played a HUGE role since all you see on there are these hourglass stick-thin bodies, and I just couldn’t handle it. I feel like now society’s standards are actually fueling my ED, even celebrities, who I liked, who I wouldn’t have called skinny back then, are now all losing weight. All my social media feeds would give me videos of what I consider «thinspo».”

Clover, 22, nonbinary:

“I’ve deleted Instagram. But a mild pattern of disordered eating QUICKLY turned into major self-hatred and anxiety — after seeing posts of plus-sized women doing various things, just literally chilling, and the comments being so incredibly vile and hateful!”

Anonymous user:

“Somehow, I found myself on eating disorder Twitter, scrolling through tips and tricks, learning ways to control my body that felt powerful, even if they were destructive.”

Beyond the digital world, cultural narratives also play a role. Fitness culture prizes control and discipline; the fashion and beauty industries promote unattainable aesthetics; and even casual peer talk — from school teasing to office banter — instils shame early on. Together, these forces turn body ideals into social expectations with direct consequences for mental health.

Body Image and Social Diversity

Body image concerns and the eating disorders they trigger are still widely perceived as a “female” problem, which means that men with EDs are often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed. Studies show they are more likely to be treated for depression or anxiety while the underlying eating disorder goes unnoticed. This diagnostic gap leaves many men without access to appropriate treatment.

Gender

Masculinity adds another layer of complexity. Instead of the thin ideal, many men internalise the “cult of muscles” — a drive for leanness, strength, and visibly toned physiques. Research indicates that muscle-oriented disordered behaviours (excessive protein intake, compulsive exercise, performance-enhancing substances) are particularly prevalent among men and often overlooked by diagnostic frameworks designed around thinness.

Sexuality

Within queer culture, body image pressure can be even sharper. Certain ideals — from the “twinkish” thin body to the muscular frame — are elevated as markers of desirability. Gay and bisexual men frequently report feeling excluded or “not queer enough” if their bodies don’t fit these fickle moulds. These community-specific expectations may intensify the risk of body dissatisfaction and even BDD.

Ethnicity & Migration

Understanding gender and sexuality in eating disorders also requires an intersectional lens that includes migration and ethnicity. A recent review of migrant populations found that acculturation stress, exposure to Western thinness ideals, and cultural identity conflicts all shape body image dissatisfaction and disordered eating. In some cases, relocation increases pressure toward thinness, while strong ties to ethnic identity can act as a buffer. Yet, most diagnostic tools are still built on Western norms, risking blind spots for diverse groups.

So, Why Does Body Image Make a Difference?

Body image is not about vanity — it is a core part of mental health. When dissatisfaction hardens into obsession, it can lead to body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) or eating disorders, both expressions of pathological fixation on the body.

Social media and cultural ideals intensify these risks, especially among young people. Yet awareness and anti-stigma efforts show that change is possible. Recognising body image as a public health issue brings hope for a future where self-worth is no longer tied to a mirror. On tough days when self-confidence sinks, Reddit user Clover suggests a simple grounding trick: “Say out loud, ‘it will be okay’,’ even if you don’t totally believe it. Take a walk with pleasant music. Nature and folk music really help me detoxify my negative self-talk and remember the bigger picture in life.”

FAQ

- What is body image?

Body image is the mental picture and feelings we have about our own body. It includes how we see ourselves, how others perceive us, and the cultural standards we compare ourselves to.

- How is body image different from body dysmorphic disorder?

Body image concerns are common and often flexible, while BDD is a psychiatric disorder marked by obsessive, fixed worries about appearance that cause severe distress and daily impairment.

- Do men experience body image issues, too?

Yes. Although eating disorders are often seen as a “female problem,” men also struggle. They are more likely to be underdiagnosed, and their concerns usually focus on muscularity and leanness rather than thinness.

- How does body image relate to eating disorders?

Negative body image is one of the strongest predictors of eating disorders like anorexia, bulimia, and binge eating disorder. Dissatisfaction with weight or shape often drives restrictive diets, binge–purge cycles, or compulsive exercise.

- What treatments exist for eating disorders and BDD?

The foundation of treatment is nutritional rehabilitation, combined with evidence-based therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). In severe cases, patients need medication and multidisciplinary care.

- How much do society and social media influence body image?

The impact is strong and well-documented. Constant exposure to cultural ideals and appearance-focused content on social media like TikTok or Snapchat increases comparison and raises the risk of eating disorder symptoms. Time spent on Instagram is directly linked with lower self-esteem and body satisfaction.