Reading Navigation

How Psychedelics Make Us Feel Connected — To Ourselves, Nature, and Each Other

For thousands of years, human beings have consumed psychedelic substances for pleasure, spiritual development, and wellbeing. Now, following decades of prohibition, they are gaining traction as innovative mental health treatments for conditions such as anxiety, depression, and addiction.

Research shows that psychedelics can break1 us out of rigid thought patterns and reveal new perspectives on ourselves and the world. But beyond the scientific data lies the lived psychedelic experience — and how this mind-altering voyage is changing people’s lives.

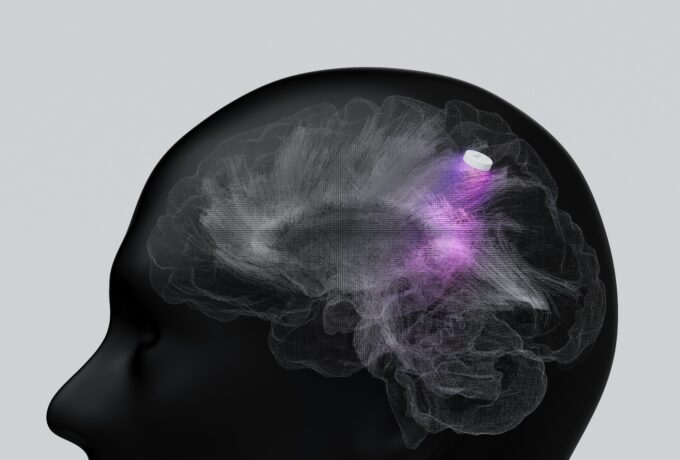

The Brain and Body On Psychedelics

Science now allows us to observe what is happening in the brain when we take a psychedelic substance, but what is it about the visceral phenomenological experience that makes us feel better?

Psychedelics work by eliciting effects on different networks and receptors in the brain, which impact the way we think and feel. For example, in a study looking at psilocybin for resistant depression, researchers found participants’ depressive symptoms improved following treatment.

One of the involved networks is the default mode network (DMN), which plays a role in self-reflection, daydreaming, and recalling the past, for example. Research shows that people with depression2 display increased or decreased activity in this network, and between the DMN and other networks in the brain. The study found that following psilocybin treatment, participants had a reduction in this hyperconnectivity.

Psychedelics seem to give us that sense of connection to other humans, to nature, and to life itself.

Translating this into the lived experience, the study participants described feelings of relief from rigid or negative thought patterns and a sense that their brain had been ‘reset’ and was able to break free of negative thought patterns.

Psychedelics also act on 5-HT2A receptors: serotonin receptors found in the brain which play a role in processes such as mood, emotion, and perception. Studies have shown that psychedelics help to induce primary process thinking — which are unconscious thought patterns — through activation of 5-HT2A receptors, creating more blissful and emotional states3.

These studies reveal how the impact of psychedelics on the brain translates into emotional feelings that improve our mood and wellbeing.

Nature and Community Connection

Many people who’ve had a psychedelic experience report feeling more connected to nature and of being one part of a larger whole.

In studies, these feelings have been linked to improved therapeutic outcomes. For example, research has shown that people who use psychedelics experienced increased nature connectedness4 up to two years following their use .

Interestingly, it revealed that this feeling of connection was positively correlated with ego-dissolution — the feeling that their sense of self or separateness from the rest of the world has “dissolved”.

Adam Ryde from the University of Oxford, who specialises in Clinical Neuroscience, has carried out research5 looking at the effects of psilocybin for depression. Ryde highlights the therapeutic nature of these feelings of ego dissolution, making people feel good by bringing them closer to nature.

“A big part of it is about feeling closer to our environment,” says Ryde. “And that isn’t just other people, but also plants, animals, and the natural world.

In a study of cancer patients treated with psilocybin6, 80% of participants demonstrated decreases in depressed mood and anxiety, and improvements in attitudes about life…

“I think what really matters is belonging. It’s so deep in us as humans to want to feel part of something bigger. Social psychology often talks about group mentality, and psychedelics seem to give us that sense of connection to other humans, to nature, and to life itself. You see yourself as part of a bigger cycle. That sense of belonging, I think, is what truly makes us feel good.”

Highlighting that modern society has become hyper-individualised and disconnected in the wake of social media, Ryde suggests that psychedelics can help people get back in touch with their sense of community, connection and belonging.

Research has found that this may be the case, with studies revealing the psychedelic experience increases feelings of social connectedness7 in participants.

“Our brains today look almost the same as they did thousands of years ago,” says Ryde.

“Physiologically, we haven’t changed much, but socially and culturally, we’ve changed a lot. What makes us happy and fulfilled, though, is the same as it always was — closeness to others, to nature, and to something bigger than ourselves.

“That’s also why psychedelics are gaining traction. They can quickly give people that sense of belonging. Meditation can do it too, but it takes more practice. I read a quote once: “Psychedelics show you, meditation teaches you.” I think that’s true.

“Both can lead to presence, connection and belonging, but psychedelics give people a glimpse much faster.”

The Mystical Experience

Psychedelics can also induce mystical experiences, where people may feel they have experienced the divine or ‘god’.

Along with ego-dissolution, nature connectedness and eliciting feelings of bliss, mystical revelations have also been linked to improved therapeutic outcomes. Such an experience has been described as involving transcendence of time and space, a sense of unity, deeply positive moods and ‘ineffability’.

Ryde highlights that the mystical experience can impact our perception of the world and our place in it. For this reason, these fresh perspectives can help with end-of-life anxiety, says Ryde.

For example, in a study of cancer patients treated with psilocybin, 80% of participants demonstrated decreases in depressed mood and anxiety6, and improvements in attitudes about life, the self and relationships.

The study noted that mystical-type experiences during treatment were strongly linked to improved outcomes, with participants reporting these experiences as spiritually significant, and that they improved life satisfaction and provided a greater sense of purpose.

“If you feel part of a larger energy or whole, something as frightening as death becomes less daunting,” says Ryde.

“All major religions, in their own way, talk about the same thing — that we’re part of something greater than ourselves,” explains Ryde. “Whether you call it God, Allah, Buddha, or simply energy, it’s that unifying idea of belonging.

“That’s the therapeutic part of psychedelics too. They loosen rigid, negative thought patterns and remind us we’re connected, we’re part of something more. That realisation itself can improve wellbeing.”

The Argument For Studying Pleasure

Research shows how these feelings of connectedness to nature and our community, or mystical revelations and ego-dissolution, can improve therapeutic outcomes. However, outside of mental health, people seek out psychedelics for pleasure and recreation.

So, is it worth understanding why people seek out their use for this purpose?

Ian Hamilton, honorary fellow in addiction at York University, believes that understanding why psychedelics make us feel good could inform how we use or regulate them. Hamilton highlights that while we have extensively studied the harms of drugs, the use of drugs for pleasure isn’t studied at all.

He argues that, as the majority of people who use drugs don’t develop addiction problems, studying pleasure might also help those who do develop problems.

“There’s a sizable group of people who use drugs regularly and remain functional, and never come into contact with the criminal justice system. Why don’t we know more about these people and their experiences?,” asks Hamilton.

“Studying pleasure could inform treatment by showing us when drug use tips from pleasure or feeling good, into harm, which is probably a very individual journey. There may be common triggers. For example, it could be that a life event such as a divorce or financial stress pushes someone along the pleasure–problem continuum.”

Hamilton suggests that if we knew why this happens, we could offer early intervention and advice, and learn which substances are more likely to create problems quickly, and which are less risky.

He suggests that acknowledging drug-induced pleasure could reduce stigma, inform drug policy, and normalise a more balanced view of drug use.

“Acknowledging pleasure might help us move away from the narrative that drugs are bad and bad people use them,” says Hamilton.

“Stigma takes time to shift, but it does shift. Policy is trickier. Pleasure has already been acknowledged in policies around cannabis.

Hamilton suggests there’s a strong case for recognising the pleasure side of drugs like cannabis or psychedelics.

“We’re stuck in a binary when it comes to drugs: it’s either all harm or all good. In reality, it’s more balanced. Alcohol is a good comparison, as most people drink without developing problems, but some do. That doesn’t mean we close every pub.”

Hamilton says that, looking ahead, regulation will be key if we are serious about acknowledging drug-related pleasure.

“Sensible regulation could reduce harm while allowing adults to make informed choices,” says Hamilton.

It’s becoming increasingly clear that psychedelics provide opportunities. To remind us of something both ancient and profoundly human: our need for connection, meaning, and joy. Whether through mystical insight, a renewed bond with nature, or simply a break from rigid thought patterns, these substances offer a glimpse into what makes us feel whole. The challenge now is how science, society, and policy can integrate this knowledge into safe, ethical, and accessible care.