Reading Navigation

Medical Cannabis Is Legal In the UK, But Patients Still Face Barriers

When Paul Matthews received his private medical cannabis prescription his quality of life changed dramatically. Living with fibromyalgia and two prolapsed discs, Paul was now in less pain and no longer needed opioids.

While medical cannabis has come a long way in the UK since its legalisation, there are still a number of barriers that patients face when accessing medical cannabis.

Paul, a representative of United Patients Alliance (UPA) which has been advocating for medical cannabis for patients since 2011, says that reduced costs, improved medicine variety and a need for a more patient-centred approach are vital for improving medical cannabis access.

Medical Cannabis in the UK: A Problem With Prices

Due to tight restrictions, patients can only access cannabis through the NHS for a select number of conditions, such as severe forms of epilepsy or multiple sclerosis.

This means that only a handful of people are receiving a cannabis prescription on the NHS, according to a Care Quality Commission (CQC) report.

The report says that it could not publish the data on the number of NHS cannabis prescriptions as “the number of items prescribed in the NHS is so small that this could potentially breach patient confidentiality.”

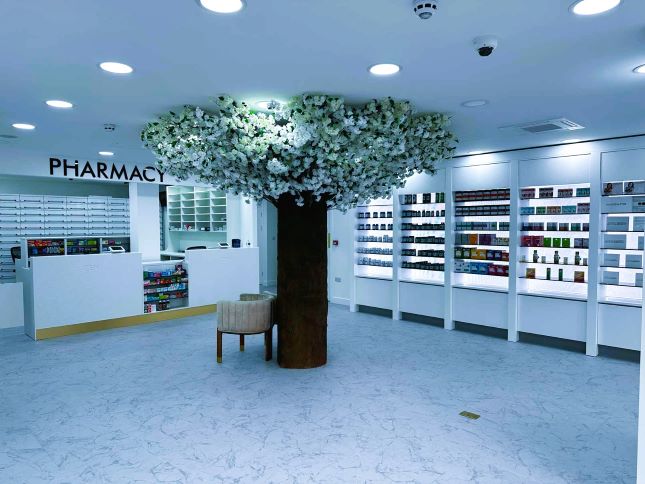

For the large majority of patients, the medicine is accessed through private clinics, meaning they must pay for consultations alongside their prescriptions.

“I know that it is amazing for me, but the affordability is difficult. It has always been a struggle, and cost is one of the issues that so many people are struggling with,” says Paul.

While costs have decreased since the start of legalisation, with clinics offering prices that rival the black market, Paul says that it is not just the consultations but the cost of the medicine itself.

“I feel the business model mirrors the illegal market,” says Paul.

“The cannabis is sold at the same prices as dealers and the same marketing strategies are used — high costs for certain strains. It’s not about helping patients. If it were, there would be affordable strains available for those who need them.

“We end up trawling through trying to find the cheapest strain, because that cost difference means meals to people like me.”

Medical cannabis patient and UPA representative Sarah Foxall, echoes this concern, noting that this is a driving factor behind patients’ continued use of the black market.

Sarah also notes that paying for the medicine impacts vulnerable patients whose conditions limit their ability to work.

“A lot of people living with chronic conditions are on low or no income because they can’t work, so the cost of consultations and prescriptions quickly becomes unmanageable,” says Sarah.

“That financial strain often pushes some patients back to the illegal market just to afford their medicine.”

Currently, clinics impose limits on the amount of medicine that can be prescribed each month, which can impact a patient’s quality of life.

Paul explains that the amount he needs to be able to live without pain means he has to choose between having a minimal amount and titrating the medicine, or having the amount that he needs “which I can’t really get”.

“This is why we need to push for people to be able to get it on the NHS or for it to be legalised,” says Paul.

Sarah adds that although the price of legal medicinal flowers has come down over the last six years, products are often cheaper on the black market.

“Especially if you’re buying in larger quantities. Legal prices stay fixed regardless of how much you buy, and high-quality products tend to be much more expensive legally than illegally,” says Sarah.

Problems With Medical Cannabis Quality in the UK

Patients are reporting problems with the quality as well as the variety of cannabis medicine available to them.

Despite the UK producing up to 109.5 tonnes of cannabis per year according to a 2024 United Nations report, the majority of cannabis received by patients in the UK is imported from countries such as Canada, Australia and Spain.

This means that when medicine reaches a patient, THC content has often reduced due to its time in storage and transit. There have also been reports of mouldy products, which can pose significant health risks.

Paul notes: “The medicine can be stored too long in sealed plastic bags rather than proper humidity containers, and there have been reports of mouldy products. It is not encouraging for people to move to the legal market.”

They said they couldn’t recommend it because they didn’t know enough … but he saw my recovery and was genuinely impressed.

Both Sarah and Paul note that improving the variety of options available, such as oils, creams, and gummies and patches, could improve patient accessibility. “The range of consumption methods is tiny,” Paul says.

“Doctors often resist recommending smoking or vaping as a treatment, but if they could prescribe a gummy or oil, it would be a more accessible and acceptable option.”

Sarah says the solution is long-term NHS access that treats medical cannabis like any other prescribed medication, suggesting that increasing the number of access or subsidy schemes could help support low-income patients.

Lack of Awareness on Benefits of Medical Cannabis

When Sarah had to undergo several major reconstructive surgeries on her legs, she was prescribed strong pain medication including morphine, fentanyl, and oxycodone, but Sarah ended up addicted to morphine.

“I was addicted to morphine twice, both times through hospital treatment, and I received no support to come off it,” says Sarah.

“I had to research and taper myself, with help from my support network. It was awful. The system leaves patients in a vulnerable position.”

Having already had experience of trying cannabis, Sarah noticed how effective the plant was for her pain.

“My GP didn’t really want to talk about it,” says Sarah. “They said they couldn’t recommend it because they didn’t know enough. My surgeon at the specialist hospital was more open-minded, he couldn’t officially endorse it, but he saw my recovery and was genuinely impressed.”

That cost difference means meals to people like me.

Sarah explains that she stopped taking all prescribed painkillers and switched to cannabis products, making a faster recovery than expected.

To tackle the issue of awareness, Paul and Sarah believe that there needs to be further training among medical professionals, who are hesitant to prescribe a medicine they know little about.

“Stigma is still a big issue. Many doctors don’t have any training in cannabis-based medicine or the endocannabinoid system, so they lack confidence in prescribing it,” says Sarah.

“Most people still think of cannabis purely as a recreational drug. We need medical professionals and public figures to help change that narrative.”

Improving Medical Cannabis Research

Currently, there’s a limited amount of clinical trial evidence for medical cannabis and only three licensed cannabis-based medicines in the UK: Epidyolex, Sativex, and Nabilone. However, none of these are broadly licensed for chronic pain, the condition affecting the majority of patients seeking access.

All other cannabis medicines are prescribed unlicensed, and can only be prescribed by doctors registered on the General Medical Council’s Specialist Register.

In addition to improved education on cannabis for medical professionals, there needs to be more recognition of the evidence that already exists on the benefits of medical cannabis, says Sarah.

While the UK ran a real-world evidence trial, Project T211, on the safety and efficacy of medical cannabis from 2020 to 2024, advocating for NHS funding of medical cannabis treatments, the UK has yet to fund any cannabis clinical trials or further prescriptions.

Cannabis has transformed my quality of life. There’s no comparison with traditional medications. Without it, I’d be unable to talk.

“Regulators and guideline bodies need to see real-world data from patients. People dismiss us as “stoners”, but thousands have documented real, measurable benefits,” Sarah says.

Adding to accessibility barriers, cannabis is not a first-line treatment, meaning patients must try up to two other treatment options before being referred for cannabis.

Paul wants to see this change so that cannabis could be a first-line option for pain patients.

“It is safer than most painkillers and works on different receptors. In severe cases, it can work well alongside opioids. Everyone should be able to use what gets them through the night,” says Paul.

“We are all self-monitoring, patients should be trusted to report their own adverse effects and manage their care collaboratively. People want to help build real evidence.”

To move forward, Paul and Sarah say patient involvement is key to improving accessibility and improving patient quality of life.

“Cannabis has transformed my quality of life,” says Paul.

“There’s no comparison with traditional medications. Without it, I’d be unable to talk. With it, I can communicate freely. The twitches and twinges from fibro are mitigated by the relaxation it provides. Opioids leave me tense and affect my speech, my hands claw up.

“Cannabis allows me to live with a level of comfort that nothing else offers.”