Reading Navigation

BPD vs NPD: The Fine Line Between Borderline and Narcissistic Patterns

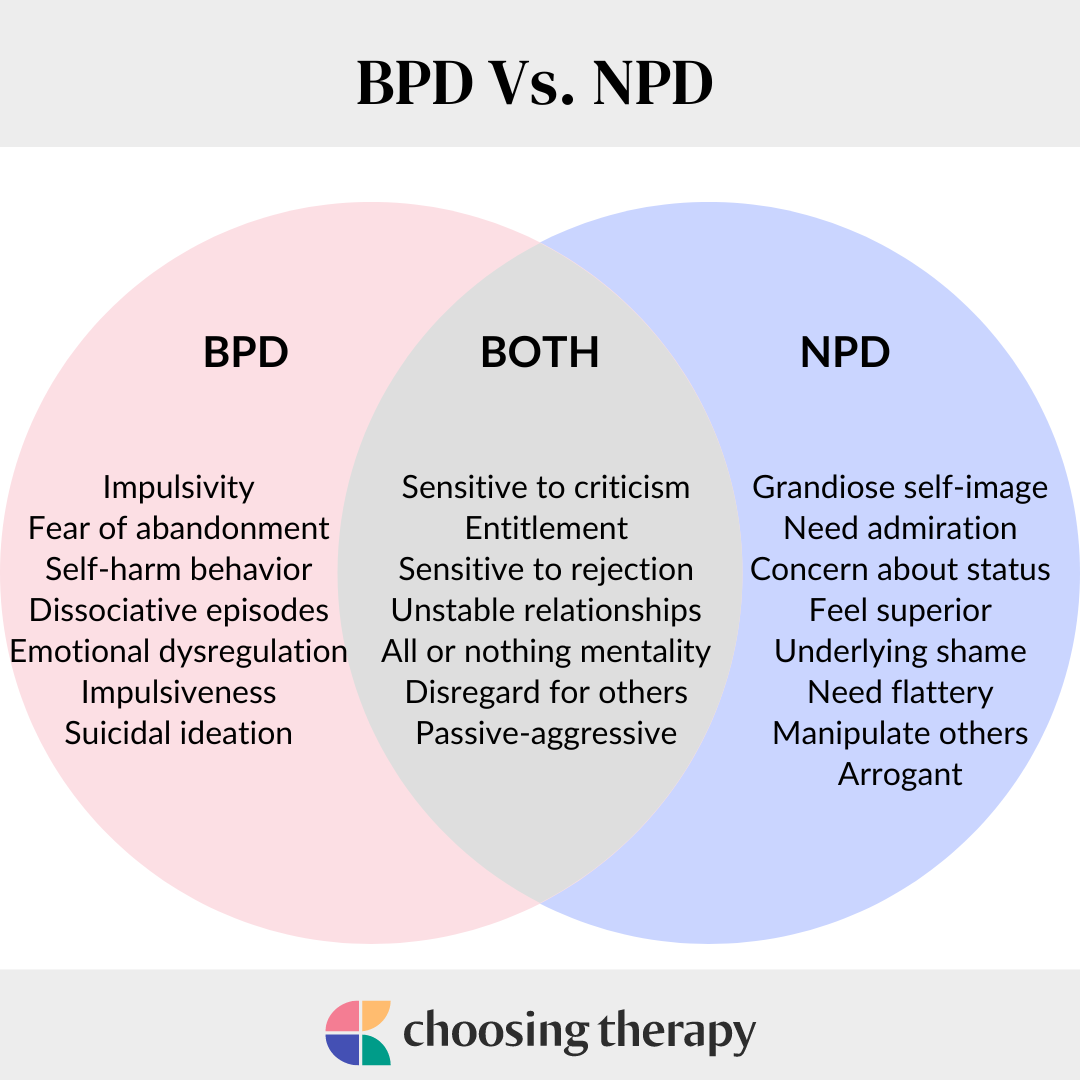

Estimates as high as 37% of people1 with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) also meet criteria for Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) — a striking overlap that often leads to misdiagnosis. Both belong to the same Cluster B group of emotional and dramatic disorders, marked by mood swings, impulsivity, and unstable relationships. A lot of people sometimes confuse them or mistake rapid emotional shifts for bipolar disorder, where mood changes are biological rather than relational. So, how can we distinguish between emotional chaos born of fear and that born of ego?

What Are Personality Disorders? The Cluster B Context

According to DSM-5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, a personality disorder is anenduring pattern2 of inner experience and behaviour that deviates markedly from cultural expectations. It’s inflexible and pervasive, and leads to distress or impairment in functioning. These patterns are typically ego-syntonic, meaning the behaviours and perceptions feel natural or justified to the individual. This distinguishes them from conditions like anxiety or depression, which are ego-dystonic. However, BPD can also be ego-dystonic, though generally it’s ego-syntonic.

Within this diagnostic framework, Cluster B personality disorders comprise the “dramatic, emotional, and erratic” group: Borderline Personality Disorder3 (BPD), Narcissistic Personality Disorder4 (NPD), Antisocial Personality Disorder5 (ASPD), and Histrionic Personality Disorder6(HPD). Individuals in this cluster often display7 emotional dysregulation, impulsivity, and unstable interpersonal relationships, though their emotional motivations differ.

- In BPD, the driving fear is rejection or abandonment.

- In NPD, the fear centres on inadequacy or loss of status.

- In HPD, the core anxiety is being unseen or ignored.

- In ASPD, the threat lies in losing dominance or control.

Emerging evidence suggests that these conditions share overlapping neurobiological pathways. 2022 Research in Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy8 proposes that personality pathology (particularly NPD) may stem from dysregulation in the positive valence system9, the brain’s network for processing motivation and reward. When this system is impaired, emotional validation or achievement may trigger exaggerated reward responses, potentially reinforcing maladaptive cycles of impulsivity, emotional extremes, and self-defeating interpersonal behaviour.

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD): Fear of Abandonment

Borderline Personality Disorder is a Cluster B condition defined by10 instability in mood, self-image, and relationships, along with impulsivity and a persistent fear of abandonment.

- Intense, rapidly shifting emotions

- Unstable or fragmented self-image

- Impulsive or self-destructive behaviours (e.g., substance use, risky spending, other reckless and irresponsible activities)

- Extreme fear of rejection or being left alone

- “Splitting” — seeing others as all good or all bad

- Cycles of idealisation and devaluation in relationships

- Chronic feelings of emptiness or boredom

- Outbursts of anger or despair that feel uncontrollable

- Impulses to self-harm

- Additionally, episodes or abnormal perceptions, including brief paranoid or dissociative experiences (usually stress-related and temporary)

These symptoms are often linked to attachment trauma12 and inconsistent caregiving. Children who experience caregivers as unpredictable or invalidating may grow up hypervigilant to signs of abandonment, equating closeness with danger.

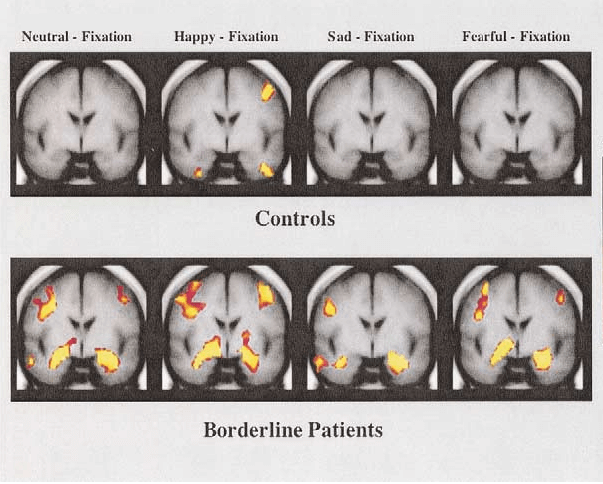

Some neurological research shows that people with BPD have a hyperreactive amygdala, the brain’s emotional alarm centre, and reduced regulation from the prefrontal cortex, which manages impulse control and reasoning. This imbalance explains why even minor relational stressors can trigger overwhelming emotional responses. At its core, BPD reflects a nervous system conditioned by uncertainty, a constant tug-of-war between longing and fear:I crave connection but expect rejection.

Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD): Fear of Vulnerability

Narcissistic Personality Disorder is defined by13 a pervasive pattern of grandiosity, need for admiration, and lack of empathy, beginning in early adulthood and present across contexts. Individuals with NPD often appear confident and self-assured but rely heavily on external validation to sustain their self-esteem. Beneath the facade of superiority lies deep insecurity and a fragile sense of self-worth.

- Inflated self-importance or exaggeration of achievements

- Fantasies of power, success, or ideal love

- A constant need for praise and attention

- Sensitivity to criticism or perceived failure

- Exploitative or manipulative behaviour

- Emotional detachment and lack of empathy

- Arrogant or entitled attitude

- Believing they are special and unique

- Sense of superiority or emotional disconnect from others

- Belief that everyone is envious of them

Two main subtypes of NPD are often described as14:

- Overt (grandiose) narcissism, marked by dominance, charm, and confidence, with open displays of superiority.

- Covert (vulnerable) narcissism, marked by hypersensitivity, defensiveness, and shame — a quieter form of grandiosity built on fear of inadequacy.

Early experiences often shape this defensive structure. NPD tends to develop in children who receive conditional love, where approval depends on performance or achievement, or in those who experience emotional neglect, criticism, or overvaluation without genuine affection. At the same time, permissive parenting (i.e., lenient, affectionate, non-conditional love) has been also associated with development of grandiose narcissism.

Neuroscientific findings support this pattern. Studies show increased activity in the ventral striatum15, the brain’s reward centre, during moments of ego reinforcement — and a sharp decline when that reinforcement is threatened. This dynamic creates hypersensitivity to both validation and criticism.

In essence, NPD is less about arrogance than protection, a way to control exposure and avoid the pain of inadequacy. The emotional core can be summed up simply: I fear exposure, so I perform perfection.

Overlaps, Comorbidity, and Diagnostic Confusion

Clinical studies show that Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) and Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) often co-occur, with overlapping symptoms1 such as impulsivity, unstable self-image, and reactive mood swings, making clear differentiation difficult.

This contributes to diagnostic overshadowing: cases where emotional chaos typical of BPD is mistaken for narcissistic entitlement, or when the controlled detachment of NPD conceals underlying instability. Similarly, bipolar hypomania, marked by confidence surges and elevated self-esteem, is sometimes difficult to distinguish8 from narcissistic grandiosity.

The core distinction lies in duration and context. Trait-based (part of one’s personality) grandiosity — stable, ego-syntonic, and interpersonal, typical for NPD. State-based (temporary shift) grandiosity — episodic, mood-driven, and reactive and often ego-dystonic, determines borderline disorders.

According to studies, narcissism is best understood dimensionally8 — part of a continuum of affective instability. The link lies in dysregulation of the neural circuit that processes reward, validation, and motivation, explaining why these conditions often overlap yet remain distinct in origin and treatment.

Shared Ground: Emotional Dysregulation

Both BPD and NPD show a core feature of emotional dysregulation16 — sudden, disproportionate mood or behaviour shifts often described as “switching”. Neuroimaging studies reveal a shared pattern17: an overactive amygdala (emotional alarm) and weakened prefrontal regulation (impulse control), which explains why even minor stressors can provoke intense reactions.

In BPD, switching follows perceived rejection or abandonment, leading to splitting — viewing others as “all good” or “all bad”. In NPD, it follows ego threat, criticism, or loss of admiration, triggering narcissistic rage or collapse. Unlike bipolar disorder, where mood shifts are episodic and biochemical, these fluctuations are relationally triggered8: reactions to rejection or loss of validation rather than shifts in brain chemistry.

Common Roots: Attachment and Development

Both BPD and NPD emerge from disruptions in early attachment, often linked to how love was given or earned. These disorders represent two distinct strategies for surviving emotionally unreliable environments.

Attachment Pathways

Research shows that BPD is often associated with disorganised and ambivalent attachment12 styles, where caregivers are both a source of comfort and fear or anxiety. This creates early hypervigilance to abandonment and a nervous system wired for emotional alarm. By contrast, the entitlement aspect of NPD was associated with dismissive attachment18. At the same time, grandiose NPD is most closely associated with preoccupied attachment styles.

Developmental Mechanisms

Chronic emotional invalidation is thought to shape the brain’s stress–reward circuitry. Scientists propose that early attachment failures alter the positive valence system19, the network regulating motivation and reward. When validation becomes unpredictable, the system oscillates between seeking and defending. This leads to a constant need for reassurance in BPD, and evolves into dismissiveness of criticism to protect one’s ego in NPD, reinforcing superiority and emotional distance.

The Middle Ground — Borderline-Narcissistic Personality Disorder

Some individuals develop what clinicians call “borderline narcissism” — a vulnerable narcissistic subtype that blends self-doubt with a craving for admiration. These individuals often swing between self-loathing and grandiosity, showing both borderline reactivity and narcissistic defence. This hybrid pattern may explain why comorbidity between BPD and NPD1 has been estimated to be as high as 37% in some clinical samples.

BPD vs NPD: Key Differences

Although Borderline Personality Disorder and Narcissistic Personality Disorder often appear similar on the surface (volatile emotions, unstable relationships, and a hunger for validation), their internal worlds have key differences.

People with BPD are driven by the terror of abandonment. They crave closeness and reassurance yet fear rejection so deeply that they often sabotage the very connection they seek. Emotional expression is raw and visible: crying, panic, rage, or self-blame when love feels uncertain. Their pain is directed inward: “I’m the problem.”

People with NPD, on the other hand, are driven by the terror of inadequacy/exposure13. They protect themselves from this fear through control, superiority, and emotional distance. While the borderline person pleads not to be left, the narcissistic person demands to be admired. Emotion is hidden behind detachment, arrogance, or charm. Their pain is projected outward: “You’re the problem.”

Relationships also take opposite forms. For someone with BPD, love can feel like a desperate pursuit: constant reassurance, intense highs and lows, and a fear of losing the “favourite person.” For someone with NPD, love can be more like a controlled performance20: admiration must flow one way, and vulnerability is avoided at all costs.

Psychologically, BPD tends to be unstable but self-aware (ego-dystonic); those affected often recognise their pain and seek help despite emotional chaos. NPD, in contrast, is stable but resistant to insight; the protective grandiosity that shields the ego also blocks self-reflection (ego-syntonic). As therapist Elvis Rosales explains, “BPD is more rooted in an internal battle with one’s emotions and fear of abandonment, while NPD tends to revolve around maintaining a superior self-image at the expense of others.”

At the neurobiological level, these opposing emotional strategies may share the same root. Studies propose that both disorders, NPD21 and BPD22, may be associated with oscillations between grandiosity and vulnerability, potentially driven by dysregulation in the brain’s positive valence system. In BPD, this dysregulation may manifest as desperate emotional surges and fear of loss; in NPD, as fragile superiority that collapses under criticism.

The Human Cost: Relationships and “Favourite Person”

Both disorders generate cycles of idealisation and devaluation, oscillating between dependency and domination, affection and withdrawal. These patterns are often mistaken for passion but are rooted in dysregulation.

In BPD, attachment often centres around a single “favourite person”: someone who becomes the emotional anchor23 and the perceived key to safety. The relationship swings from adoration to panic at any sign of distance. Partners describe the experience as facing unpredictable surges of affection, anger, and despair. Emotional “switching”, rapid shifts between love and rejection, is often triggered by perceived abandonment or invalidation.

In NPD, relationships revolve around control, admiration, and emotional distance. Early stages may include love-bombing — intense flattery and attention designed to secure attachment, followed by withdrawal or contempt once the partner’s admiration fades. This dynamic, often described as narcissistic abuse, stems from the narcissist’s need to regulate24 fragile self-worth through dominance and validation.

The contrast is stark: BPD whispers, “Don’t leave me,” while NPD orders, “Don’t challenge me.” This difference is reflected in the empathy paradox. Research notes that people with BPD tend to have high affective but low cognitive empathy: they feel emotions deeply but misinterpret motives. Those with NPD, conversely, show25 high cognitive but low affective empathy: they understand others intellectually but remain emotionally detached.

The result is emotional misalignment: the borderline partner absorbs and amplifies emotion, while the narcissistic partner analyses and controls it. One fears losing connection; the other fears losing control.

Treatment Plans: From Reactivity to Regulation

Recovery from Borderline Personality Disorder and Narcissistic Personality Disorder begins with regulation26 — helping the nervous system shift from survival mode to safety. Insight differences complicate treatment: BPD is usually ego-dystonic (the person feels their distress), while NPD is often ego-syntonic (defences feel natural, even justified). Yet, both respond best when therapy targets the underlying instability and maladaptive coping patterns.

Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT)

Originally developed by Marsha Linehan in 1993, DBT remains27 the most evidence-based treatment for BPD. It teaches four key skill sets — emotion regulation, distress tolerance, mindfulness, and interpersonal effectiveness. Clinical studies show28 significant reductions in self-harm, impulsivity, and emotional volatility after one year of consistent practice.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

For NPD, CBT targets distorted self-beliefs, especially patterns of entitlement, perfectionism, and black-and-white thinking. It focuses on identifying automatic thoughts that fuel grandiosity or shame and replacing them with realistic, compassionate self-assessments. CBT also fosters empathy and self-reflection24, making it one of the most adaptable frameworks for NPD treatment, though research is still developing.

Mentalization-Based Therapy (MBT)

Developed by Peter Fonagy in 198929, MBT enhances30 the ability to “mentalize” — to understand one’s own and others’ mental states accurately. For BPD, this reduces impulsivity and paranoia by helping patients interpret others’ actions as complex rather than hostile. In NPD, MBT cultivates empathy and reduces defensive misinterpretation of criticism, making it effective for individuals with high emotional reactivity or interpersonal conflict.

Transference-Focused Psychotherapy (TFP)

Created by Otto Kernberg and John Clarkin, TFP is especially useful for patients with intense relationship instability or identity diffusion. By examining how emotions and power dynamics play out within the therapist–patient relationship, TFP helps integrate31 splintered self-images — the alternating idealized and devalued states common in both BPD and NPD.

Somatic and EMDR Therapies

Body-based and trauma-focused modalities like Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) and somatic experiencing help patients process unresolved trauma32 that fuels hyperarousal, dissociation, or emotional detachment. Though primarily used for trauma, it can support individuals with BPD or NPD when unresolved trauma underlies their emotional dysregulation. For BPD, these techniques calm physiological reactivity; for NPD, they address suppressed vulnerability and improve embodied self-awareness.

Medication and Its Role

There are no FDA-approved medications specifically for either BPD or NPD. However, psychiatrists may prescribe13 medication to treat co-occurring symptoms such as anxiety, depression, or impulsivity. SSRIs can address depressive symptoms and anxiety, while low-dose antipsychotics or mood stabilizers may reduce aggression or impulsivity. Medication should be seen as adjunctive, not curative.

Family and Group Support

Group therapy improves emotion regulation and reduces relapse by fostering shared accountability. Family therapy helps loved ones understand the cycle of emotional reactivity and detachment, easing tension and improving communication. Peer communities and online support groups also provide validation and reduce isolation.

Prognosis and Success Factors

Long-term outcomes for BPD are encouraging: many individuals experience remission of core symptoms after several years of consistent therapy, particularly DBT or MBT. NPD tends to improve more slowly, with progress depending heavily on insight, motivation, and sustained therapeutic alliance. For people with NPD, treatment is more challenging33 due to defensiveness and limited self-awareness, but meaningful change is possible with commitment and trust-building.

Factors associated with a better prognosis include early intervention, therapist consistency, and willingness to accept feedback. For both disorders, self-reflection, mindfulness, and emotional regulation can predict long-term stability and healthier relationships.

Holistic and Emerging Approaches

Integrative programs increasingly combine psychotherapy with mindfulness, yoga, meditation, and lifestyle regulation. These practices strengthen emotional resilience, improve interoceptive awareness, and complement traditional treatment by targeting the body’s stress response.

Explore Trusted Clinics and Retreats For Every State of Mind

Seeing the Person Beneath the Pattern

Suppose psychiatry continues to move away from fixed diagnostic categories. In that case, the boundary between BPD and NPD may increasingly be viewed as a continuum of emotional regulation styles rather than two distinct disorders. The DSM-5 Alternative Model already points toward this shift, describing personality pathology as a gradient of maladaptive traits and regulation patterns.

Emerging neuroscientific research supports this dimensional view. Some studies suggest that grandiosity and emotional collapse may not be opposites, but potentially alternating responses34 within the same emotional circuitry. Therapeutic models are evolving accordingly. 35In 1989, psychoanalyst Peter Fonagy introduced29 mentalization-based therapy, emphasising reflective awareness of mental states. Before that, psychologist Marsha Linehan developed Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), which framed recovery for BPD around emotional regulation and distress tolerance. Together, these frameworks highlight how disorders once seen as fixed traits are better understood as learned regulation strategies.

This shift echoes neuroscientist Thomas Insel’s argument that mental disorders are not static “brain diseases,” but circuit-level dysfunctions that can be reshaped through therapy and environment. Future psychiatry will likely move toward treating how the brain regulates emotion.