Reading Navigation

How Pop Culture Defines Autism Stereotypes: From “Rain Man” to “As We See It”

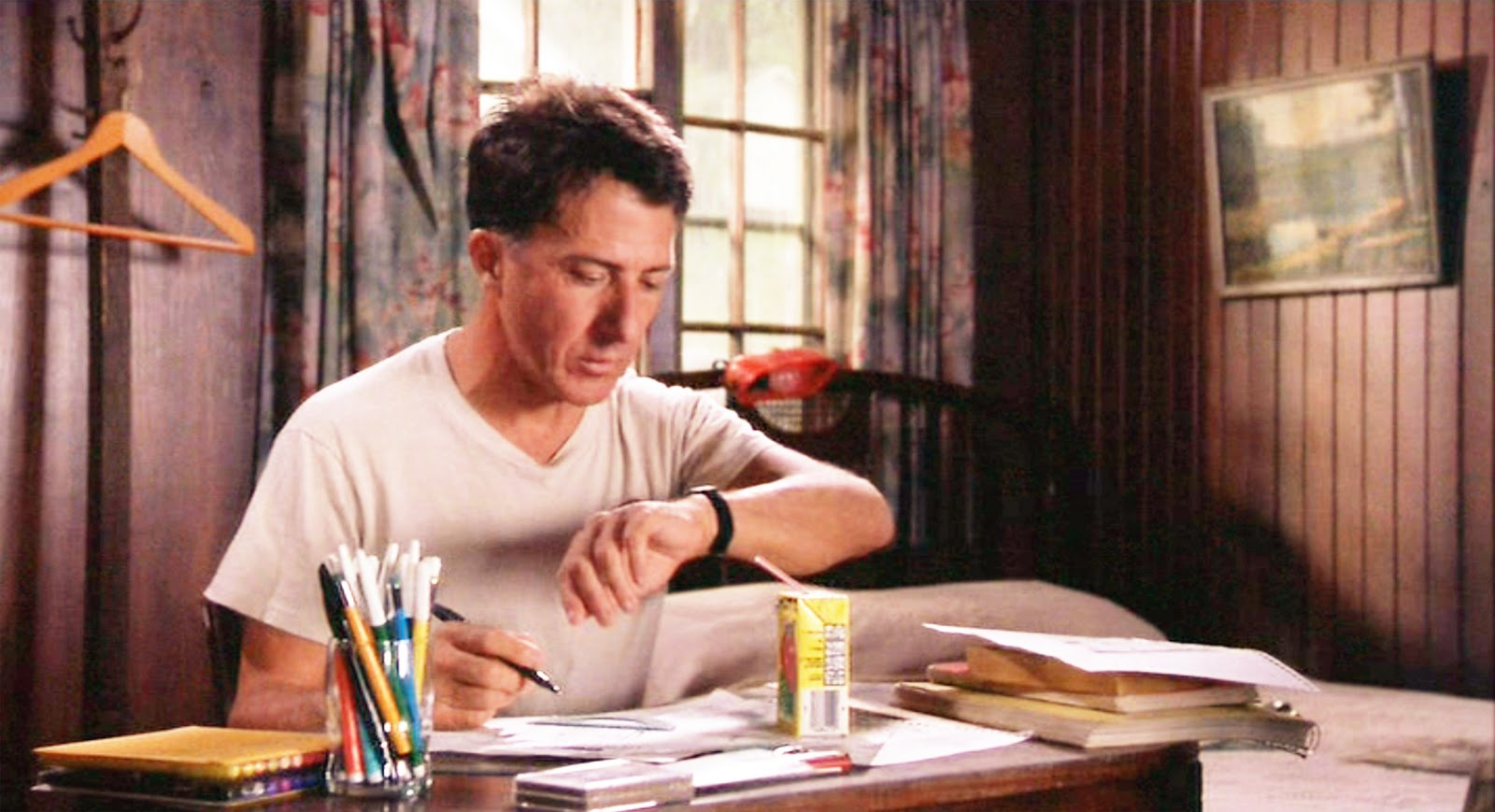

When people think of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), their first image often comes from pop culture rather than medicine: Dustin Hoffman’s Rain Man, Sheldon Cooper in The Big Bang Theory, or Sam in Atypical. These characters shaped1 how millions imagine autism symptoms — repetitive habits, social awkwardness, unusual sensory reactions, or even “savant” genius.

But real autism is broader than fiction. ASD is a spectrum: people can be verbal or nonverbal, logical or creative, independent or needing daily support. Pop culture, however, rarely shows this diversity — instead, it repeats stereotypes that oversimplify autistic traits and fuel stigma. But what if the stories we binge-watch don’t just entertain us, but quietly rewrite how society sees autism itself?

How Autism First Appeared on Screen

For many viewers, the modern story of autism in pop culture begins with Rain Man (1988), where Dustin Hoffman’s Raymond Babbitt is presented as an autistic savant2. This portrayal helped raise awareness of the condition, becoming hugely influential, yet it cemented a narrow public image of autism as a rare genius paired with social difficulty. The film’s cultural reach was enormous, and its “savant” framing has echoed across later portrayals.

Across the 1990s and early 2000s, that template hardened. Popular characters read by audiences as “autistic-coded” (brilliant yet socially awkward) kept linking autism with exceptional intellect while giving little space to everyday variability. A systematic review1 of fictional media finds that portrayals frequently lean on a small set of recognisable traits and extremes rather than breadth and nuance.

By the 2000s and 2010s, autism had become a familiar theme in both sitcoms and medical dramas. Atypical on Netflix put a high-schooler on the spectrum at the centre of a family dramedy. At the same time, The Good Doctor built a hit around an autistic surgeon with savant skills — another globally visible iteration of the “brilliant but different” archetype. Critics have noted that such shows tend to emphasise the verbal, higher-skilled end of the spectrum and can leave more complex realities off-screen. Analyses in media and reviews in academic journals highlight how visibility often came without diversity.

Some pop characters are written as openly autistic — like Shaun in The Good Doctor. Others (for example, Sheldon in The Big Bang Theory or Abed in Community) are “coded” — never labelled on-screen but are widely read by audiences as showing autistic traits. The first approach boosts visibility; the second broadens who people see as possibly autistic — yet either one can drift into cliché.

Beyond the Quirky Genius: Autism in Modern Culture

In recent years, mainstream culture has begun to explore autism with greater diversity and authenticity. Netflix’s Atypical (2017-2021) followed Sam Gardner, a teenager on the spectrum, as he navigated independence, dating, and family dynamics. Early seasons were criticised for relying on stereotypes, but later episodes worked with autistic consultants, demonstrating how collaboration can transform a series into a more accurate representation.

Global productions have pushed the conversation further. Extraordinary Attorney Woo (2022), a South Korean drama that became a Netflix sensation, portrays Woo Young-woo, an autistic lawyer balancing professional challenges with personal growth. The series was praised for its warmth and relatability, though experts noted it still centres on the high-functioning end of the spectrum.

Amazon Prime’s As We See It (2022) brought a new level of authenticity by casting three autistic actors — Sue Ann Pien, Rick Glassman, and Albert Rutecki — as autistic housemates. The writing team also included autistic consultants, which gave space for more realistic depictions of sensory overload, social struggles, work challenges, and even internalised ableism. Viewers highlighted how refreshing it was to see an autistic woman of colour on screen, especially in storylines about dating and sexuality — areas where autistic people are too often stereotyped as childlike or desexualised.

Authenticity has also grown in the way stories are created. In the Heartbreak High reboot (2022), a character named Quinni — played by autistic actor and activist Chloë Hayden — is written with her lived experience in mind. Storylines about “masking” and the sting of being told “you don’t look autistic” reveal everyday realities rarely shown in earlier portrayals.

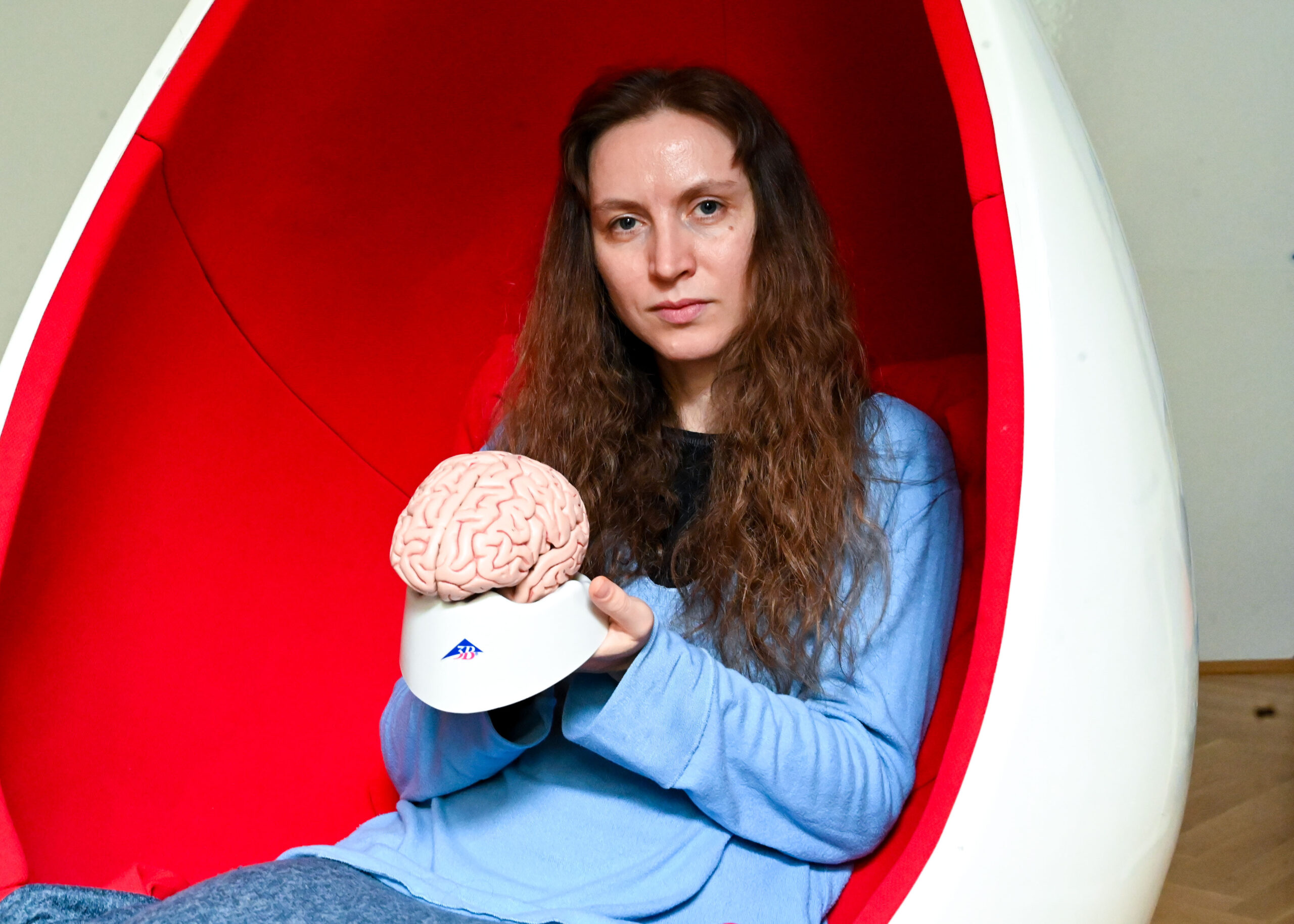

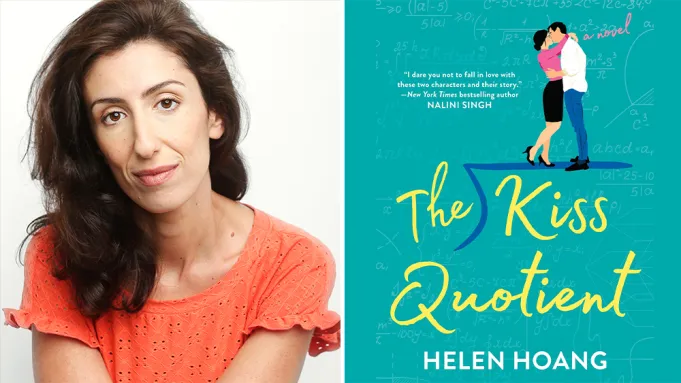

Beyond television, autistic voices are also reshaping mainstream publishing. Authors are no longer confined to memoirs or niche non-fiction — they are writing bestselling romance, mystery, and young adult fiction, and their characters reflect lived experience.

Helen Hoang’s The Kiss Quotient introduced a neurodiverse heroine into a spicy romantic novel — genre that rarely acknowledges autism. At the same time, Brandy Schillace’s The Dead Come to Stay places an autistic protagonist at the heart of a modern mystery. These stories matter not only for representation but for reach: they land on bestseller lists, spark fan communities, and challenge readers to imagine autistic life as multifaceted, adventurous, and sometimes messy.

However, the autistic community has mixed feelings about these books. Some readers note, “The Kiss Quotient” shows an authentic portrayal of an adult neurodivergent woman navigating romance, helping them finally see themselves in a story. On the other hand, some criticise it for still having a high-functioning focus and outdated Asperger’s framing (though it was intended to contrast stereotypes).

Autism Stereotypes Pop Culture Just Won’t Let Go

Even as autism gains more visibility, pop culture still circles a handful of clichés. These myths shape how audiences think, how doctors diagnose, and even how autistic people see themselves. Reviews of fictional media show1 that stereotypes are far more common than nuanced depictions.

1. All autistic people are geniuses

It suggests that every autistic person has extraordinary skills in math, memory, music, or other areas. In reality, savant abilities are rare — researchers estimate3 they occur in only a small fraction of people on the spectrum. Studies show that 59% of people with ASD have average or higher IQ, and the other half accordingly may need extra support and a better understanding from the neurotypical people.

2. Autistic people don’t feel emotions

On screen, autistic characters are often portrayed as robotic or emotionally flat. Yet studies show4 autistic people feel empathy and deep emotions just as much as neurotypical people. However, they may express them differently or struggle to decode social cues. This myth can be especially harmful, leading others to dismiss autistic people as “uncaring.”

3. Autism is a male condition

Most fictional autistic characters are white boys or men. It reinforces the false idea that autism is primarily male5. Though ASD is 3 times6 more common among boys than among girls, in reality, women and non-binary people are often underdiagnosed because their traits can present differently.

4. Autistic people can’t form relationships

Films and shows often isolate autistic characters, implying they are incapable of romance or friendship. In reality, autistic individuals date, marry, have families, and form strong friendships. When “Heartbreak High” introduced Quinni, a teenage autistic girl exploring relationships, it challenged the infantilization that autistic people often face.

5. Autistic people fear or reject touch

Sensory sensitivities7 are real, but not universal. While some autistic people dislike certain textures or physical contact, others seek out touch and enjoy intimacy. Media portrayals that treat “no touch ever” as a defining trait erase the diversity of sensory experiences on the spectrum.

6. Autism prevails in children

News reports and TV dramas often focus on autistic children, like Max Braverman from “Parenthood” — usually with worried parents or teachers. Adults with autism8 are rarely visible in the media, even though autism is a lifelong condition. It fuels the misconception that people “grow out of it,” and leaves adult needs underrepresented.

7. Autistic people are dangerous or uncontrollable

Though rare in fiction, some portrayals frame autistic people as unpredictable or even violent. Research9 consistently shows the opposite: autistic people are far more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators. This stereotype can feed fear and discrimination.

8. All autistic people act nearly the same

Pop culture often recycles identical traits: monotone speech, an obsession with routines, eccentric habits, and awkward body language. While these traits exist, they don’t define the entire spectrum. Autism varies enormously in expression, and reducing it to one “type” denies that diversity.

Break Free From Stereotypes About Your Mental Health

Hashtags and Headlines: Autism in Social Media

In pop culture, autism is often still framed within specific scripts and storylines — and it’s essential. Meanwhile, content platforms like YouTube and TikTok give autistic creators direct space to share their realities, challenging stereotypes and broadening representation.

On YouTube, “educational” videos about autism dominate search results, but research shows that the comments under them skew negative, with scepticism and stigma outweighing support. TikTok has amplified autistic voices through hashtags like #ActuallyAutistic, where creators share personal experiences of masking, sensory overload, or dating. At the same time, studies warn that much of the autism content on TikTok is of mixed quality — engaging but often oversimplified or romanticised.

Despite these risks, content platforms provide autistic creators with unprecedented space to tell their own stories, thereby broadening representation and challenging stereotypes. Influencers such as Paige Layle, with millions of TikTok followers, use humour and honesty to normalise everyday autistic life. On Reddit and in blogs, communities like r/AutisticPride highlight not only challenges but also pride in neurodivergence, creating a counter-narrative to the deficit-focused framing that still dominates mainstream headlines.

In the age of hashtags and headlines, the story of autism is no longer confined to Hollywood scripts. It unfolds daily in viral videos — spaces where stereotypes can also spread fast, but where authentic autistic voices are finally being heard.

Toward Real Representation

The key to honest representation lies in diversity — of characters on screen and of creators behind the camera. From children’s shows to global campaigns, more projects are giving space to people with ASD. Sesame Street introduced Julia, a Muppet developed with autistic consultants to reflect everyday experiences like sensory sensitivity and friendship. PBS Kids launched Carl the Collector, a series featuring two autistic lead characters, helping children see themselves — or their peers — on screen.

Media and brand campaigns also challenge the old narratives. The UK charity “Ambitious about Autism” ran “Me, My Autism & I” in collaboration with Vanish. It’s raising awareness about how autistic girls are often overlooked in diagnosis and pushing back against the stereotype that autism is only male. The campaign focuses on the vital role clothing can play in helping autistic people feel supported. For 75% of autistic people, keeping the look, smell and feel of clothes the same is important.

For broad audiences, the takeaway is clear: dive into stories that feature autistic consultants and actors, look for characters that reflect the diversity of the autism spectrum, and question portrayals that reduce autism to a single “quirky” trope. Real progress is no longer a distant goal — it’s unfolding in real time. The words like “autism” or “Asperger’s” no longer call up just “Rain Man” or Elon Musk, but a growing mosaic of stories. New portrayals chip away at the old clichés and make space for a spectrum — varied and complex as the people they represent.

*Featured image: "As We See It" Series Cover, 2022. Source: Amazon Prime Video