Neurodivergence and the Brain: How Minds Differ — and Thrive

Up to one in five people are considered neurodivergent — their brains perceive, process, and respond to the world in ways that differ from what’s usually defined as “typical.” However, the actual number may be significantly higher, as many individuals never seek or receive a formal diagnosis.

What began as a term used by sociologist Judy Singer in the late 1990s to describe the diversity of human brains has now entered workplaces, classrooms, and social media bios. The rise of neurodivergence isn’t just about medical recognition — it’s part of a larger cultural shift in how we understand difference itself.

Instead of asking what’s wrong, society is beginning to ask what’s unique — and what that means for how we live, learn, and connect.

What Is Neurodivergence?

Neurodivergence refers to the natural differences in how people think, feel, learn, and interact with the world. The term describes variations in brain function and behaviour that fall outside what society defines as “typical” — not as disorders, but as forms of diversity. In other words, it’s a way to recognise that no two minds are wired in exactly the same way.

Someone who is neurodivergent might experience attention differently — finding it hard to concentrate on uninteresting tasks but entering a deep state of hyperfocus on topics they are passionate about. Another person might process language visually rather than verbally, or feel overwhelmed by bright lights and background noise. Others might move or communicate in ways that challenge social expectations, like needing time to respond, pacing while thinking, or avoiding eye contact.

Neurodivergence reminds us that there is no single correct way for a brain to work — only many ways of being human.

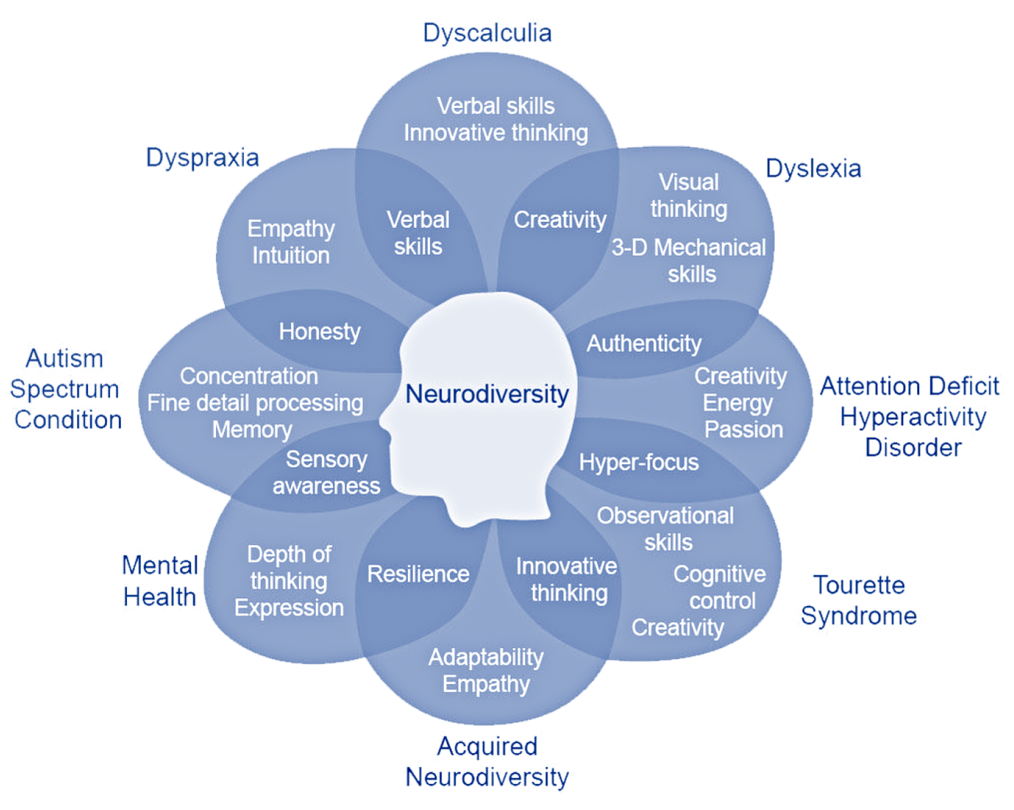

A core tenet of neurodivergence is accepting that these differences are not flaws or signs of something “wrong.” They’re part of the spectrum of how human brains operate — shaped by genetics, environment, and experience. Neurodivergence encompasses a wide range of cognitive and sensory styles, including ADHD, autism, dyslexia, dyspraxia, social anxiety, and more.

Rather than viewing these traits through a medical or deficit lens, the concept encourages a broader, more compassionate view of human variety — one that sees difference as design. Research published in Frontiers in Psychology supports this shift, showing that many adults who identify as neurodivergent describe it as a more accurate way to understand themselves.

Who Is Neurodivergent? Rethinking “Normal”

The concept of neurodiversity was first introduced in the late 1990s by Australian sociologist Judy Singer, who sought to provide people with a language to describe neurological differences without labelling them as deficits. Singer’s idea was simple but revolutionary: just as biodiversity makes ecosystems resilient, neurodiversity makes humanity adaptable.

What began as a concept within the autism rights movement quickly grew into a broader conversation that now includes ADHD, OCD, Tourette Syndrome, dyslexia, dyscalculia, dyspraxia and other forms of cognitive variation. Over the past two decades, the neurodiversity movement has shifted from advocating for acceptance to demanding systemic inclusion — in education, healthcare, and the workplace. It argues that the problem doesn’t lie within neurodivergent people, but in the environments that fail to accommodate different ways of thinking.

As psychologists note, neurodiversity is “more than just a new perspective on the brain” — it challenges the very idea of what counts as normal. Instead of trying to fit everyone into the same cognitive mould, the goal is to design systems flexible enough to support many styles of learning, perceiving, and creating.

The next phase of this evolution, described by Hari Srinivasan as Neurodiversity 2.0, goes even further. It bridges science and lived experience, calling for collaboration between researchers, clinicians, and neurodivergent individuals themselves. The author frames it as a scientific and social necessity — a way to build environments where all brains can participate fully.

The Many Forms of Neurodivergence

Neurodivergence is an umbrella term describing multiple ways of processing, learning, and experiencing the world. Each form reflects distinct cognitive and sensory patterns, yet the boundaries between them are fluid. Many people experience co-occurring traits across several categories — for example, ADHD alongside anxiety, or autism with dyslexia. Here are some of the most recognised forms of neurodivergence:

ADHD (Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder)

ADHD is associated with differences in dopamine pathways and executive function — the mental skills responsible for focus, organisation, and impulse control. Rather than an attention deficit, people with ADHD often describe it as attention variability: difficulty focusing on uninteresting tasks but the ability to hyperfocus on things that spark curiosity.

Autism Spectrum Disorder

Autism spectrum disorder encompasses a wide range of experiences that influence sensory perception, communication, and social interaction. Autistic individuals may be highly sensitive to sound or light, prefer routine, or process language literally — but also often demonstrate strong pattern recognition, deep focus, and creative problem-solving.

Dyslexia, Dyspraxia, and Dyscalculia

These learning and coordination differences affect reading, writing, spatial reasoning, and movement. Dyslexia alters how the brain processes language, dyspraxia impacts motor coordination and planning, and dyscalculia influences the ability to understand numbers and mathematical relationships. With supportive tools — like visual learning aids or adaptive technologies — these differences can become alternative strengths.

OCD (Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder)

OCD involves repetitive thoughts (obsessions) and behaviours (compulsions) that are used to reduce anxiety or regain a sense of control. While traditionally categorised as a mental health disorder, some researchers and neurodivergent advocates view OCD as part of the neurodiversity spectrum — a distinct cognitive style linked to heightened awareness, perfectionism, and pattern-seeking.

Anxiety

Anxiety is often experienced alongside ADHD, autism, or OCD — not necessarily as a separate disorder, but as part of the neurodivergent experience of heightened sensitivity and awareness. Chronic stress from navigating a neurotypical world can intensify anxiety, especially in environments that demand constant masking or overstimulation.

The concept of neurodivergence and related conditions. Source: Johns Hopkins University

Diversity of Signs and Symptoms

Because the term covers a broad spectrum, there is no single checklist that defines it. Still, clinical sources and recent peer-reviewed studies outline several common patterns shared across neurodivergent populations:

- Sensory sensitivity — heightened or reduced sensitivity to light, sound, textures, smells, or movement. Everyday environments, such as open offices or bright classrooms, can easily trigger sensory overload. This aligns with findings on sensory reactivity in autism and ADHD.

- Intense focus or difficulty shifting attention — some people struggle to maintain attention on routine tasks but can enter deep states of hyperfocus when something captures their interest. Attention variability is a well-documented feature of autism and related conditions.

- Differences in emotional regulation — stronger emotional responses, difficulty recovering from stress, or needing time alone after social interaction. Research shows that co-occurring identities (such as gender expression and sexuality) can amplify emotional strain in neurodivergent individuals.

- Nonlinear thinking and creativity — a tendency to think “outside of the box”, making intuitive leaps, thinking visually or associatively, and connecting ideas in unconventional ways. Neurodiversity studies describe this as a hallmark of cognitive richness and divergent problem-solving.

- Challenges with time, planning, or social cues — difficulties with executive function (planning, time estimation, task switching) and interpreting implicit social signals. These traits are frequently observed across ADHD and autism research.

- Feeling “out of sync” in group settings — many neurodivergent people describe a lifelong sense of being slightly out of rhythm with the world around them, despite functioning successfully in it. It echoes qualitative findings from lived-experience research on identity and masking.

It’s essential to remember that not everyone experiences these traits in the same way: some find their differences empowering, others find them exhausting. Many experience both at once. Neurodivergence exists not as a fixed identity but as a continuum of human experience.

Neurodivergent Tests and How to Use Them

Online tests can help identify thinking or behavioural patterns, but they are not diagnostic tools. A diagnosis requires a comprehensive assessment by a trained clinical professional — interviews, developmental history, and behavioural observation. Here are the most commonly used and evidence-based screening instruments:

- AQ (Autism Spectrum Quotient) — measures autistic traits in adults.

- RAADS-R (Ritvo Autism Asperger Diagnostic Scale – Revised) — detects autism in adults, especially those undiagnosed in childhood.

- ASRS (Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale) — WHO screening tool for adult ADHD.

- DIVA-5 (Diagnostic Interview for ADHD in Adults) — structured interview used in clinical ADHD assessment.

- SDQ (Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire) — screens emotional symptoms, hyperactivity, and social behaviour.

Many people also self-identify as neurodivergent based on lived experience. Research shows that self-recognition can support acceptance and well-being even without a formal diagnosis.

The Neurodiversity Movement: From Awareness to Inclusion

The neurodiversity movement emerged in the late 1990s from within online disability communities led by autistic and ADHD self-advocates who rejected the idea of being “patients” in need of fixing. They reframed their conditions as natural variations of human cognition — differences that deserve respect, accessibility, and representation.

Over the next two decades, the movement expanded from small online forums into an international network connecting education, science, and policy. Its mission evolved from awareness to inclusion — challenging institutions to adapt to different ways of thinking and learning, rather than forcing people to conform to narrow norms.

Today, the movement is presented by a diverse ecosystem of organisations working toward systemic change:

- Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN) — founded in 2006 by Ari Ne’eman and colleagues, ASAN campaigns for representation in legislation, healthcare, and education, operating under the motto “Nothing about us without us.”

- Neurodiversity in Business (NiB) — a UK-based nonprofit that partners with over 200 employers, including Microsoft, BBC, and JPMorgan, to promote neuro-inclusive hiring, management, and workplace culture.

- Understood.org — a U.S. platform providing research-backed resources for families, educators, and adults with ADHD, dyslexia, and other learning differences.

- Neurodiversity Hub — an Australian initiative connecting universities and employers to support neurodivergent students transitioning into professional environments.

- RE-STAR — a participatory research model, where young people with ADHD and autism collaborate as co-researchers, shaping study design and data interpretation.

Across these initiatives, the movement pursues several shared goals:

- Policy reform: embedding neurodiversity principles into education, the workplace, and accessibility legislation.

- Workplace inclusion: implementing flexible schedules, quiet spaces, and transparent communication.

- Inclusive research: adopting models where neurodivergent people lead or co-author studies.

- Public awareness: dismantling stereotypes and amplifying lived experience in media and culture.

- Equity in healthcare: ensuring identity-affirming, interdisciplinary, and trauma-informed care.

According to the Neurodiversity 2.0 framework, which bridges science and advocacy, the next stage is practical equity — moving from token awareness to systemic integration. The goal is interdependence: communities designed for collective care and mutual support. The reason is simple: When we listen to lived experience, we create systems where every mind has space to thrive.