Reading Navigation

The Neuroscience of Integration: How Our Brains Can Create Lasting Change

The human brain has an incredible ability to adapt itself by breaking old habits and ideas to form new ones. Our brains are made up of billions of neurons, and we learn behaviors by creating pathways between them. When we have a habit — like smoking — we repeat the action so often that these neural pathways are strengthened, making them automatic behaviors that are difficult to break.

Despite this, we can change our habits by disrupting old neural pathways and creating new ones. Yet in order to make these changes last, integrating new habits into our lives is crucial.

We take a closer look at the science and speak to the experts exploring how we can change our brains.

Rewire Your Brain With Better Habits

Memory consolidation is the process by which newly learned information becomes stabilized and stored for long-term use in the brain; and over repeated practice it can support the formation of new habits. For example, if someone attempts to quit smoking by drinking green tea instead of having a cigarette, each time they repeat this new behaviour it strengthens a new neural pathway, contributing to lasting change.

Similarly, memory re-consolidation is the process of updating old memories or habits in a new light, such as changing a behavioural response to a past trauma.

These processes are particularly important for issues such as addiction — which research shows can “hijack” memory and learning to form maladaptive associations1 between certain cues (imagine wanting a cigarette after a meal).

Research suggests that memory re-consolidation could offer a way of ‘rewiring’ these memories and associations to reduce relapse risk.

Memory reconsolidation is the brain’s process of updating or modifying old memories when they’re reactivated. During this brief window, emotional or traumatic memories can be modified—making it a key mechanism behind lasting change in therapies like EMDR, somatic work, and psychedelic-assisted healing.

Professor of Behavioural Neuroscience at the University of Cambridge, Amy Milton, has been studying memory re-consolidation in her lab, investigating re-consolidation-based approaches for the treatment of mental health disorders such as PTSD and drug addiction.

Professor Milton says that memory re-consolidation is widely considered to have evolved to allow memories to update.

“Contrary to what we might think, memory is often more useful for predicting the future, such as how we should behave in a similar situation going forward, than reminiscing about the past,” explains Professor Milton.

While integration practices such as therapy, journaling, or meditation aim to reinforce new insights or habits — consistency is key, as habits take time to form.

“In order to make good predictions, we need to be able to update memories in light of new information.

“However, we also need to be careful not to update memories when this would not be helpful. Therefore, there is a delicate balance between our prior expectations, the current sensory evidence we are receiving, and whether we update an old memory, or form a new one.

“For example, you wouldn’t want learning words in a new language to overwrite your learning of the same words in your native language — instead, you need to form a separate memory that you can use in a different situation.”

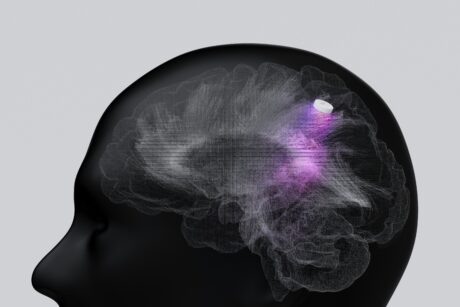

Brain Plasticity and Psychedelic Medicines

Recently, research into psychedelic medicines suggests that these compounds can enhance neuroplasticity. Studies have found that, during and following a psychedelic experience, there is a “window” of time2 in which this brain plasticity is increased, enabling old thought patterns to be disrupted and new ones to be more easily formed.

Neuroplasticity is the brain’s ability to rewire itself, forming new neural connections and replacing old ones. It’s how we break habits, form new behaviors, and recover from trauma. This neural flexibility is the foundation for learning and healing. Studies show that psychedelics and other therapies can increase neuroplasticity.

Given this feature of the compounds, they are now being researched for their potential as treatments for addiction, such as for gambling and smoking addiction, as well as for the treatment of mental health conditions such as PTSD and anxiety.

Associate professor of neuroscience at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Dr. Dustin Hines focuses his research on understanding brain function. In particular, his work seeks to understand how other cells influence memory consolidation and the integration of new experiences, as opposed to focusing on neurons alone.

Hines has also been researching psychedelics — where he has found that these treatments generate specific patterns of brain activity linked to behavioural changes.

“Our research was the first to demonstrate brain signatures of psychedelic therapeutic effects and specifically identified two characteristic slow EEG waveforms,” explains Hines.

“Integration is vital in order to understand the experience and create lasting change from the insights or changes made following the experience.

“Uncovering these waveforms gave us a powerful window into how psychedelics modulate brain circuits — they momentarily shift network dynamics in a highly predictable, signature-specific way that goes beyond subjective experience.

“Because these patterns are tightly time-locked to behavioural shifts, they suggest a rhythmic, orchestrated state in which brain circuits become particularly plastic.

“By mapping these signatures across phases, we gained much deeper insight into the mechanisms of psychedelics and not just what changes, but when and how those changes align with behaviour.

Find Support to Match Your Needs

Integration To Help With Lasting Change

Research suggests that the ability of psychedelics to induce this state of brain plasticity may contribute to its effects in the treatment of depression3, anxiety, and addiction2.

What might be key to this process is integration4 — both before and after a psychedelic experience. This can include tools and techniques such as psychotherapy, meditation, journaling or connecting with nature, for example.

Critically, this can be implemented during the window of plasticity where new neuronal connections can be formed.

For example, studies have shown that psychedelic medicines that are delivered in conjunction with psychotherapy have improved clinical outcomes, in particular for mental health conditions and addiction5. Some research has suggested6 that traumatic memories can also resurface during a psychedelic experience.

“In terms of integration from a psychedelic perspective, when old memories are potentially being re-assessed and updated during a psychedelic experience, it is tempting to speculate that re-consolidation might be involved,” says Milton.

“We are very interested in the hypothesis that psychedelics may affect prior expectations, and allow re-consolidation to occur under circumstances where it might perhaps not happen otherwise.

While integration practices such as therapy, journaling, or meditation aim to reinforce new insights or habits, Milton emphasises that to establish a habit, consistency is key, as habits take time to form.

“Often people find that ‘habit stacking’ is effective — using a behaviour that you already do to be the prompt for a new, wanted habit. This uses fundamental learning processes that require very little attention to maintain once the association has been made,” says Milton.

“From a memory perspective, ensuring that change endures could happen either through updating of old memories, or learning of new ones that inhibit the old ones.

Integration means helping people hold onto insights they’ve gained, or make sense of confusing or distressing content. I often think of psychedelic experiences like dreams, but in a conscious state.

For more insight into the potential of integration, we spoke with lead therapist on the COMPASS Pathway’s Phase 3 study7 investigating psilocybin for the treatment of mood disorders, Simon Critchley, who says that integration is crucial following a psychedelic experience.

“Integration is vital in order to understand the experience and create lasting change from the insights or changes made following the experience,” says Critchley.

“Some things that come up can be confusing or distressing, or people might have past traumas that re-emerge. Being able to offer support to work through those experiences is really valuable.

“There are risks — especially if someone is unprepared, in the wrong environment or in the wrong mental state. Some end up chasing repeated experiences to “fix” a difficult one, which can lead to further destabilisation.

Critchley says that preparation is equally important.

“Before someone goes into a psychedelic experience or treatment, they need to know what to expect, how to prepare, and how to handle anxiety — because it almost always comes up,” says Critchley.

“Teaching support strategies helps people get through it in the safest and most meaningful way.

“Afterwards, integration means helping people hold onto insights they’ve gained, or make sense of confusing or distressing content. I often think of psychedelic experiences like dreams, but in a conscious state — some elements fade over time, including the positive feelings, unless people actively integrate them into daily life.

“There’s a window of neuroplasticity afterwards when the brain is forming new pathways. For those to stick, people have to keep using them, otherwise they’re pruned away. Integration helps maintain and embed those new pathways so they don’t disappear, which reduces the risk of falling back into old depressive or anxious thought patterns.

While forming new habits and thoughts is one aspect, Critchley highlights that somatic feelings and emotions experienced on psychedelics can fade over time unless people find ways to reconnect with them.

“Many want to hold onto those feelings of resilience, positivity or coping, but that takes practice,” says Critchley.

“Integration supports that, whether through conversation, journaling, meditation, creative expression or connecting with nature.

“It’s not just about the drug’s neurological effect, it’s about embedding new behaviors and self-care practices.”