What If ADHD Is an Evolutionary Trait — and It’s Time We Treat It Differently?

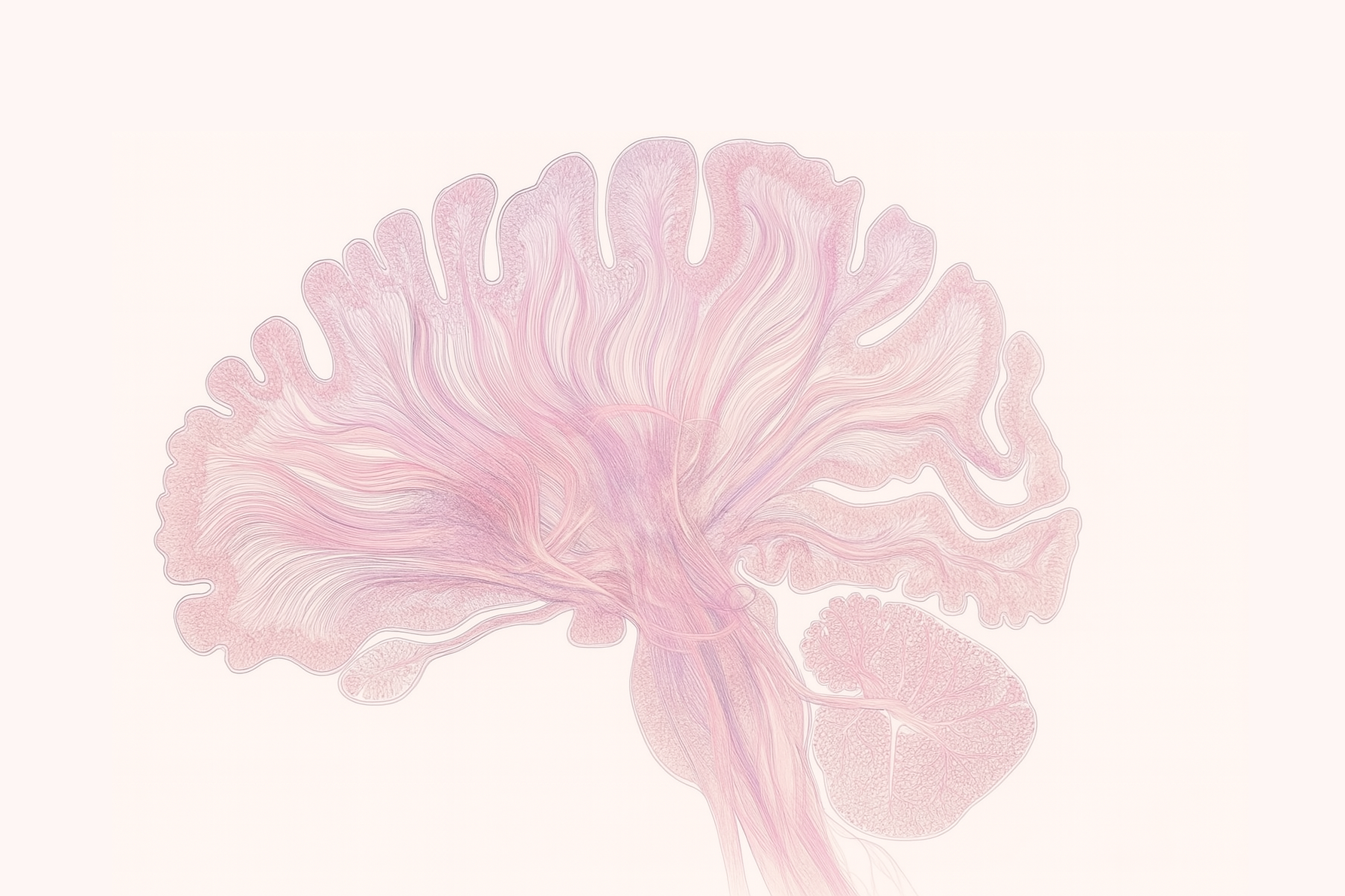

For decades, ADHD has been diagnosed and treated as a deficit of attention, executive function, and self-regulation. But a growing body of research suggests this framing may miss the point — or at least one of them. What if, rather than being broken, the ADHD brain is simply out of sync with the modern world?

Exploration Over Deficit

Human behavior is fundamentally shaped by a constant tension between exploiting known resources and exploring new possibilities. This dilemma, well-studied in biology and ecology, describes how living organisms decide when to stay with a resource that is gradually depleting and when to abandon it in search of something better.

In humans, the nomadic, exploration-oriented lifestyles have been associated with genetic mutations implicated in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), raising the possibility that this condition could have impacted foraging decisions in the general population.

Researchers from the Department of Neuroscience at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, set out to test this hypothesis. In a large study involving 457 adults, they combined self-reported ADHD symptom scores with an online “berry-picking” game that simulated foraging decisions — asking participants to decide when to leave a depleting resource patch, with varying travel times to new ones.

Everyone in the study stayed longer in one place when it took more time to reach a new one. But people with more ADHD-like traits left sooner — and surprisingly, they ended up earning more rewards. Their choices matched what scientists call “optimal foraging”, meaning they made smarter, more efficient decisions about when to move on. Similar patterns have been found in nomadic groups linked to ADHD-related genes, and brain research suggests this behavior may be tied to how their attention and decision-making systems work.

These findings suggest that ADHD brains aren’t necessarily “flawed” by nature, they’re just better suited for exploring and moving on, rather than staying focused on one thing. But modern schools and workplaces expect something different, the authors argue, and this clash may be what causes the struggle.

This view doesn’t deny the struggles ADHD brings. Rather, it situates them in context. When rapid idea generation, environmental sensitivity, or hyperfocus occur in a system that rewards prolonged attention to unengaging tasks or rigid scheduling, those same traits quickly become liabilities.

Understanding ADHD as a form of evolutionary mismatch opens new possibilities for treatment approaches that support rather than suppress these traits. It encourages the development of interventions tailored to enhance cognitive flexibility and emotional regulation, helping individuals harness their intrinsic strengths without being overwhelmed by anxiety, impulsivity, or executive dysfunction.

But what does this mean for treatment?

This shift in perspective has practical consequences. It opens the door to treatments that support, rather than suppress, the ADHD brain. Traditional stimulant medications like methylphenidate and amphetamines enforce sustained attention by increasing dopamine availability in the prefrontal cortex. For many, they’re effective. But they also come with side effects and don’t work for everyone.

In recent years, ketamine has entered the psychiatric landscape as a radically different kind of intervention. Though not approved for ADHD, and not recommended as a first-line treatment, it has shown rapid efficacy for treatment-resistant depression, anxiety, and PTSD. Now, early anecdotal reports and emerging neuroscience are beginning to explore ketamine’s potential relevance for ADHD.

Unlike stimulants, ketamine does not artificially enhance focus. Instead, it appears to restore cognitive flexibility, modulate emotional reactivity, and recalibrate dysfunctional brain network activity — specifically, the default mode network (DMN), which is often hyperactive in both depression and ADHD.

Research published in Molecular Psychiatry has shown that ketamine rapidly enhances neuroplasticity by increasing glutamate transmission and promoting the growth of new synaptic connections. This could be especially relevant for people with ADHD who struggle not only with attention but also with emotional regulation, task inertia, and working memory — issues linked to inefficient connectivity between prefrontal and limbic brain regions.

One possible mechanism involves the TPH2 gene, which regulates serotonin synthesis in the brain. Altered TPH2 expression has been implicated in impulsivity and behavioral disinhibition — both core traits of ADHD. Ketamine’s impact on serotonergic systems, alongside its well-documented glutamatergic effects, may help recalibrate these imbalances. While studies on TPH2 and ketamine remain limited, the connection opens intriguing avenues for further research into personalized, mechanism-based treatments.

Take the case of James, a creative director in New York who struggled for years with a blend of ADHD-like symptoms and mood instability. Stimulants made him irritable and erratic. It wasn’t until he received a different diagnosis — a rare bipolar variant — and began ketamine nasal spray treatment, that things shifted. Within weeks, James reported improved emotional regulation, clearer thinking, and a dramatic reduction in anxiety. Though not a typical ADHD case, his story underscores the possibility that ketamine may address overlapping symptom domains or ADHD comorbidities in ways traditional medications don’t.

Still, it’s important to approach this territory with scientific caution. Ketamine therapy is not an approved treatment for ADHD, and existing evidence is preliminary at best. Systematic reviews have not found any strong data supporting ketamine’s efficacy in ADHD, and clinicians generally agree it should not replace first-line therapies. Controlled trials are urgently needed to determine if observed benefits are reproducible, significant, and safe over time.

Yet even in the absence of robust ADHD-specific data, ketamine’s broader effects (reducing rumination, improving mood, quieting inner chaos) may offer secondary benefits for people whose attention problems are compounded by trauma, rejection sensitivity, or chronic anxiety.

Viewed through this lens, ketamine therapy isn’t a cure, nor a stimulant substitute. It may instead serve as a circuit-breaker — a way to calm the noise long enough for the ADHD brain to access its native strengths: improvisation, associative thinking, creative risk-taking.

Ultimately, reframing ADHD as a mismatch rather than a malfunction invites more nuanced, compassionate treatment models that honor neurodiversity while addressing real suffering. Whether ketamine becomes part of that toolkit remains to be seen. But as science continues to unpack the brain’s complexity, it’s clear that supporting ADHD isn’t just about improving focus. It’s about restoring harmony to a system that was never broken, just built for a different world.