Reading Navigation

Is It Love or Anxious-Avoidant Attachment? Understanding the Pattern

- Anxious-avoidant attachment combines fears of rejection and engulfment, leading to conflicted patterns of closeness and withdrawal.

- This attachment style appears as mixed signals: seeking intimacy yet pulling away once it feels too close.

- Attachment style in adults is flexible. Secure relationships can gradually transform anxious and avoidant patterns into trust and stability.

- Therapy approaches like EFT and Attachment-Based CBT can reduce insecurity and improve emotional regulation within 6-12 months.

- Healing starts with consistent small actions that teach the brain and body that closeness is safe and predictable.

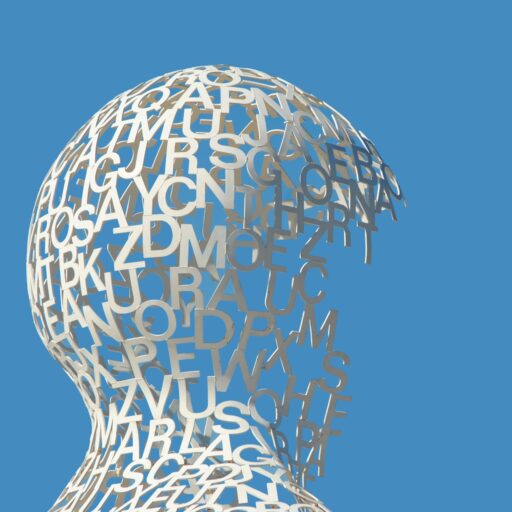

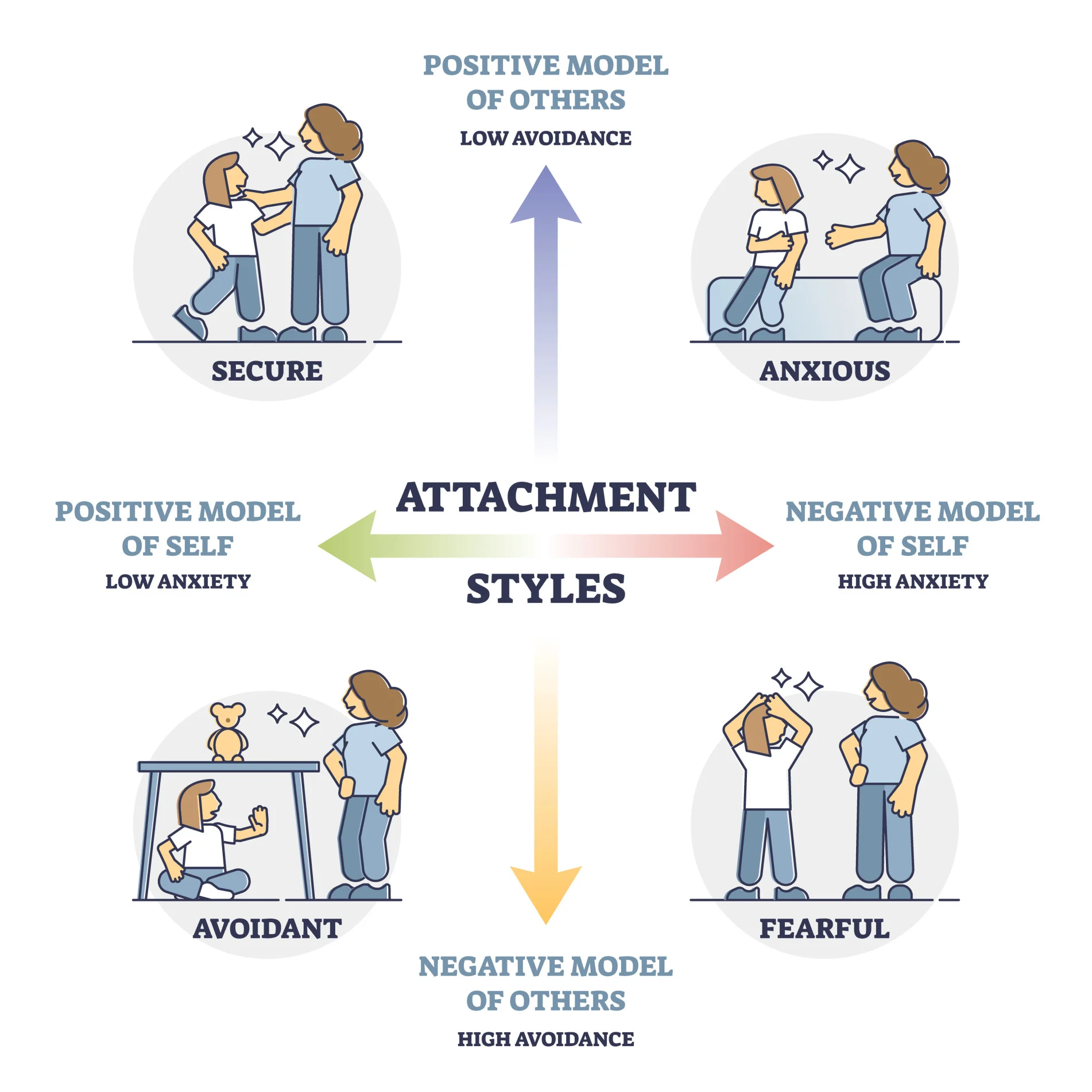

Attachment theory is a concept describing how we relate to closeness, safety1, and emotional connection. These patterns usually fall into 4 broad styles: secure, anxious, avoidant, and anxious-avoidant (also called fearful-avoidant or disorganised). In secure attachment, intimacy feels steady and safe, and people can rely on others. In insecure attachment styles, on the contrary, closeness is charged with fear — of abandonment, of control, or both.

When closeness feels magnetic and terrifying at the same time, you may be looking at anxious-avoidant attachment2 — a pattern where people crave intimacy, then shut down the moment it arrives, longing for love while fearing dependence. This style blends attachment anxiety and avoidance into one paradoxical style.

It often creates a cycle3 of pursuit and withdrawal, emotional volatility, and burnout — not only in romance, but across friendships and work relationships too. It can stem from inconsistent caregiving, emotional unavailability, or early unpredictability that taught the nervous system to both seek and fear closeness: anxious and avoidant meaning behind the pattern.

The good news is that attachment isn’t fixed. Recent studies show that these emotional models can shift4 with therapy, consistent secure experiences, and mindful awareness. Even moment-to-moment tracking confirms that attachment fluctuates dynamically and can stabilise through healing. So, what does anxious-avoidant attachment look like in adults, how it develops, and which evidence-based therapies can help rebuild connection?

What Is Attachment Theory?

It was first developed by British psychiatrist John Bowlby and psychologist Mary Ainsworth in the mid-20th century to explain how early caregiving shapes emotional development and adult relationships. Their research showed that the quality of a child’s bond with a caregiver creates an internal working model — a subconscious template for how love, trust, and safety operate throughout life.

There are 4 main styles of attachment:

- Secure attachment

- Anxious (Preoccupied) attachment

- Avoidant (Dismissive) attachment

- Disorganised (Anxious-Avoidant or Fearful-Avoidant) attachment

In secure families, where parents are emotionally available and responsive, children often learn that closeness is safe. They are more likely to develop secure attachment, characterised by confidence, emotional regulation, and comfort with intimacy. At the same time, new meta-analyses suggest these links are not deterministic5: attachment patterns are shaped by multiple factors, and childhood experiences may not fully predict adult attachment styles.

— If caregivers are emotionally distant, critical, or encourage premature independence, the result is often avoidant attachment — a pattern of emotional withdrawal and self-reliance.

— When care is inconsistent, some children develop anxious attachment6, marked by hypervigilance, fear of abandonment, and a constant need for reassurance.

— When caregiving is unpredictable or traumatic, alternating between affection and rejection, the child may develop anxious-avoidant attachment2. This style combines the anxiety of wanting closeness with the avoidance of fearing it, creating confusion and internal conflict that often persists into adulthood.

In adulthood, attachment styles are closely linked to mental health. A 2022 meta-analysis shows that higher levels of attachment anxiety and avoidance are reliably associated1 with greater depression, anxiety, loneliness, and emotional distress, and with lower life satisfaction and self-esteem. These associations remain significant across age and gender.

At the same time, attachment patterns are not fixed traits. Longitudinal studies confirm that adult attachment can shift over time4, particularly through consistent experiences of emotional safety, supportive relationships, and therapy.

What Is the Anxious-Avoidant Attachment Style?

The anxious-avoidant attachment style, sometimes called fearful-avoidant or disorganised attachment, describes people who crave closeness yet feel unsafe when it happens. It’s one of the most conflicted insecure attachment patterns: a constant tension between the need for connection and the urge to pull away. Though sometimes called an anxious avoidant attachment disorder, it’s not a clinical diagnosis but a learned pattern.

In adulthood, it often appears as anxious-avoidant behaviour7: sending mixed signals, seeking closeness but retreating when things feel too intense. These individuals might seem independent, but beneath that independence lies fear of vulnerability. They oscillate between two inner messages: “I need love to feel safe” and “Getting too close will hurt me.”

Compared with other styles, anxious individuals fear abandonment, avoidant ones fear loss of autonomy, while anxious-avoidant people fear both rejection and engulfment. This inner conflict often leads to unstable8, emotionally charged relationships that repeat the same push–pull cycle.

Though sometimes called an anxious avoidant attachment disorder, it’s not a clinical diagnosis but a learned pattern. Research shows it can be changed4 through therapy, secure relationships, and gradual exposure to emotional safety.

Signs and Traits of Anxious-Avoidant Attachment

People with an anxious-avoidant attachment style often live in two opposing states: longing for deep connection while fearing dependence. This internal conflict fuels instability, mistrust, and exhaustion for both themselves and their partners.

Common anxious-avoidant attachment signs and traits include7:

- Strong need for connection but fear of dependence. Closeness feels comforting and threatening at once.

- Mixed signals. They reach out, then pull away when intimacy deepens.

- Emotional volatility: quick shifts between affection and withdrawal. Highs and lows mistaken for passion.

- Difficulty expressing vulnerability. Emotions are intellectualised or dismissed as “not important.”

- Self-protective independence. Appearing confident or detached while quietly craving reassurance.

- Conflict avoidance or protest behaviours. Silent treatment, overthinking, or testing loyalty when feeling insecure.

- Low emotional safety. Relationships often feel uncertain, unstable, or “too much.”

- Doubting their own worthiness of love and consistent care.

How It Differs from Other Insecure Styles

- Anxious individuals fear rejection and seek reassurance, often overcommunicating or clinging to the relationship.

- Avoidant individuals fear being controlled or losing independence, so they distance themselves when emotions rise.

- Anxious-avoidant individuals carry both fears: they want closeness yet retreat the moment they feel engulfed or exposed.

During conflict, anxious partners push for immediate repair, while avoidant partners shut down. The anxious-avoidant person does both: pursuing when ignored, withdrawing when met with emotion. This back-and-forth8 is what makes the anxious-avoidant attachment style so confusing. Growth begins when both patterns are recognised: anxious tendencies need self-soothing and patience, while avoidant defences need vulnerability and presence.

How Does Anxious-Avoidant Attachment Develop?

The anxious-avoidant attachment style often (but not always) develops through early environments that mix care with rejection. Research links it to 3 main factors:

- Inconsistent caregiving

Warmth alternates with withdrawal, teaching the child that closeness is unpredictable. - Emotional neglect or unresponsiveness

Caregivers discourage emotional expression or expect early independence. The child learns self-reliance and suppresses needs. - Trauma or unpredictability

Exposure to conflict, loss, or inconsistent support links love with distress and fear.

Over time, the nervous system may oscillate9 between hyperactivation (anxious response) and deactivation (avoidant defence), producing the push-pull dynamic seen in adulthood. Neurobiological research10 suggests this pattern reflects altered stress regulation rather than a single marker. Cortisol interacts with learning and threat-detection systems in the brain, shaping how closeness is interpreted over time. Insecure attachment has been linked not simply to elevated cortisol, but to abnormal cortisol responses10, alongside difficulties in emotional regulation and heightened sensitivity to distance or withdrawal from intimacy.

The Anxious-Avoidant Relationship Dynamic

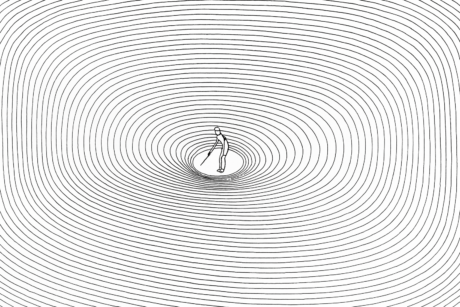

In relationships, the anxious-avoidant attachment dynamic often plays out as a repeated emotional chase: one person reaches out while the other retreats. It feels magnetic, driven by fear on both sides rather than trust or safety.

The Push-Pull Cycle

- The anxious partner seeks closeness and reassurance. When texts go unanswered or affection fades, their fear of abandonment activates. They may overcommunicate, analyse every silence, or apologise just to restore contact.

- The avoidant partner, overwhelmed by emotional intensity, withdraws to regain a sense of control. They might say they “need space,” avoid serious conversations, or become distant after intimacy.

- The more one pursues, the more the other retreats, reinforcing the chase-retreat cycle typical of the anxious-avoidant attachment style.

How It Looks in Real Life

- Partner A starts feeling anxious when their partner doesn’t respond for a few hours. He sends several messages, hoping to reconnect. Partner B, who feels pressured, delays replying — not out of cruelty, but because emotional intensity feels suffocating. Both end up hurt: A feels rejected, B feels invaded.

- After a romantic weekend, an avoidant partner might suddenly pull back, skipping plans or avoiding calls. His anxious partner senses the distance and tries harder: planning surprises, asking “Are you mad at me?”, or demanding reassurance. What began as affection turns into a cycle of pursuit and withdrawal that neither fully understands.

The outcome is predictable: short bursts of warmth followed by cold distance. Both experience emotional exhaustion and growing mistrust. Despite the pain, many stay in this dynamic because it feels familiar. In childhood, love often came mixed with rejection — so unpredictability now feels like proof of depth. This emotional confusion can even mimic connection: elevated cortisol and dopamine levels during conflict temporarily feel11 like intimacy.

Common Relationship Challenges

Relationships marked by an anxious-avoidant attachment style often run on a mentioned push-pull loop that drains trust and energy. Typically, these relationships struggle12 with:

- Constant tension. Anxious partners pursue reassurance while avoidant partners withdraw, reinforcing a push-pull cycle.

- Emotional exhaustion and burnout. High-intensity highs and lows, limited trust, and low perceived support produce chronic strain and fatigue.

- Poor communication and unresolved conflict. Patterns of defensiveness, stonewalling, and shutdown prevent resolution and keep issues recycling.

- Trauma bonding and co-dependency. The roller-coaster intensity is misread as closeness; codependency and protest behaviours keep partners stuck in the anxious-avoidant trap.

Red Flags When the Relationship Becomes Unhealthy

- Same conflicts repeating despite effort or therapy. Dyadic data show anxious+avoidant pairings reliably predict12 lower trust, satisfaction, and stability — a sign that the pattern itself is the problem.

- One partner is doing all the emotional work. Anxious partners overfunction, while avoidant partners underfunction — a chronic imbalance12 of regulation and repair.

- Feelings of worthlessness, fear, or emotional numbness. Insecure attachment correlates6 with lower psychological well-being; avoidant defences often present as emotional blunting, while anxious partners report elevated distress.

- Loss of autonomy or safety. Avoidant partners experience closeness as engulfment; anxious partners feel trapped by uncertainty — both markers of a relationship eroding3.

Therapeutic Approaches and Growth

Healing from an anxious–avoidant attachment style involves retraining the nervous system to experience closeness as safe. Therapy offers a corrective emotional experience: a consistent, attuned connection that rewires the old belief that intimacy equals danger. Modern attachment-based therapies blend4 neuroscience, emotional processing, and relational safety to rebuild secure patterns of connection.

Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT)

Developed by Dr. Sue Johnson, EFT is one of the most well-researched and evidence-backed approaches for treating attachment-related distress13 in relationships. It is particularly effective for couples caught in anxious-avoidant dynamics: rather than focusing on surface arguments, it targets the waves of pursuit and withdrawal dynamics. The goal is to transform reactive patterns into emotional accessibility.

Therapists slow interactions, label emotional triggers, and help each partner express vulnerability instead of protest. Studies show EFT success rates above 70%14 in improving trust, emotional security, and relationship satisfaction. For many couples with insecure attachment patterns, EFT is considered a first-line treatment.

Attachment-Based Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (AB-CBT)

This approach combines15 CBT’s structured methods with attachment theory. It helps individuals recognise how early beliefs (“I’ll be abandoned,” “I don’t need anyone”, etc.) drive current reactions. AB-CBT helps to replace maladaptive attachment schemas with more flexible ones.

It works through thought-emotion mapping, journaling, and behavioural experiments — such as gradually tolerating vulnerability, practising healthy boundaries, or delaying avoidance impulses.

Clients develop cognitive and emotional tools to engage safely in relationships without overdependence or emotional shutdown.

Internal Family Systems (IFS)

While IFS is best supported by evidence in the treatment of trauma, PTSD, and depression, it can be used as an adjunct approach for attachment-related difficulties. By helping clients identify and relate differently to their internal reactions, IFS may support greater emotional regulation and internal safety — capacities closely linked to more secure attachment patterns. In general, IFS approaches the mind as a system of inner “parts,” guided by a core compassionate Self. In anxious-avoidant attachment, these protective parts often manage closeness through opposing strategies — one amplifying anxiety, the other pulling away to maintain safety.

Building Secure Attachment Through Therapy

Across modalities, effective therapy shares three mechanisms:

- Awareness: recognising patterns of protest or withdrawal before they escalate.

- Safety: experiencing consistent, nonjudgmental attunement from a therapist, which reconditions fear responses.

- Practice of new behaviours: self-soothing, honest communication, and tolerating closeness without panic.

Long-term studies confirm that with regular therapy, individuals with anxious-avoidant attachment traits show measurable increases16 in emotional regulation, trust, and relationship satisfaction within 6 to 12 months. Ultimately, therapy teaches that independence and intimacy are not opposites; both can coexist within a secure attachment.

Can Attachment Styles Change? Breaking the Cycle

Attachment styles are not fixed; they are adaptive emotional strategies that can change throughout life. Research in adult attachment and therapy outcomes shows that with consistent emotional safety, self-awareness, and secure relationships, the brain forms new pathways for regulation and trust, and the person is more likely to create16 a secure attachment.

Rewiring the Pattern

Neurobiological studies indicate that repeated secure interactions reduce17 amygdala reactivity and strengthen prefrontal regulation of emotional responses. In practice, that means the nervous system can unlearn the old threat association that fuels anxious-avoidant behaviour.

Tips for the Anxious Partner

- Pause before reacting. Slowing emotional responses lowers cortisol and helps reframe perceived rejection.

- Voice needs to be calm. Secure communication reduces conflict escalation and strengthens emotional attunement.

- Keep your own anchor. Maintaining self-directed coping strategies (journaling, friendships, mindfulness) fosters self-trust and reduces codependency.

Tips for the Avoidant Partner

- Ask for space openly. Transparent communication prevents triggering a partner’s fear of abandonment.

- Stay present through tension. Even a brief verbal acknowledgement during conflict lowers defensive withdrawal and promotes empathy.

- Show reassurance. Consistent gestures, like small check-ins, physical touch, and eye contact, retrain the brain to link intimacy with safety.

Steps Toward Building Secure Attachment

Research shows that attachment patterns can shift when safety and consistency are practised repeatedly. Meta-analyses of attachment-based therapies confirm that within several months16, clients show measurable improvements in emotional regulation, relationship satisfaction, and self-efficacy. Here is a list of small, steady changes that recalibrate emotional responses:

1. Recognise triggers early

Identifying emotional or bodily signs of distress (e.g., tension, urge to withdraw) helps interrupt6 automatic anxious or avoidant reactions before they spiral out of control.

2. Set adaptive emotional boundaries

Balanced limits reduce reactivity: anxious types learn containment, while avoidant types practice controlled openness.

3. Communicate directly

Open and concise expression of needs lowers stress markers12 and builds trust over time.

4. Create a predictable connection

Small daily rituals, such as check-ins, routines, and affirmations, can lower attachment anxiety3.

5. Reinforce secure habits

Reflecting on progress and seeking empathic feedback strengthens4 self-regulation and attachment coherence.

Secure attachment grows from repetition — steady, predictable acts that teach the body and brain that closeness is safe, calm, and real.