Reading Navigation

I Wasn’t Sick, But I Wasn’t Well: A Mental Health Story

Everyone has a story. A prologue. A journey. But where do our stories begin? Is there a specific moment? A decisive and identifiable fork in the road? Or do our paths wind and weave, behind and beyond any easy attempts at classification?

For the sake of this story, and in the hope of marking and memorializing my own path, I’ll begin on the evening of an everyday Tuesday, sitting alone in my apartment, breath still heavy and tears freshly fallen, saying out loud and to myself…

OK, I think I need to do something about this.

***

About what, exactly? Hard to say. Not because it’s so complex, but rather that it feels so common.

I was raised in a middle-income (sometimes lower-middle-income) family in suburban Montreal. Divorce happened very young. There are faded memories, tinted in tension, colored with fear.

Life went on. A single mother with two young kids. A loving father far away. Not quite abandoned, yet not quite fully nurtured.

Money was tight. Conditions were fine but not ideal. Harsh realities were observed. Worries absorbed.

As the eldest child, I learned too early to accept and suppress and rationalize and cope. To consider others ahead of myself. To comfort my little sister. To try and make this life I was living into something I could live with.

Things weren’t bad. I was loved. Supported. Blessed in many ways.

But life accumulates.

You’re given pieces of other people’s burdens. Other people’s neglect. You develop habits. Not all of them are good. Childhood becomes adolescence becomes adulthood and examples you were shown become thoughts you now default to.

Life accumulates.

It begins to bulge. To weigh down on you and your attempts to live simply. You get divorced. You witness your mother die too young and its horrific unfairness breaks something inside you. You begin to worry about money. You forget to file your taxes and get hit with late fees.

Life accumulates.

And despite things being fine — more than fine, blessings innumerate — you find yourself sitting on your couch in your lovely apartment about to break down and ugly-cry.

Was it anxiety? Probably. Low-level and not thaaat bad. But there. Always there. And finally it spilled over the edges.

The negative thoughts that normally linger around our emotional peripheries had begun to take up too much space — and I was tired of it. I had given my worries too much permission, too much access. I’d become someone whose default was no longer joy; and this made me something worse than sad. Disappointed. Exhausted. Sitting there on my couch I finally spilled wide open and what came out, what was expelled, was neither laugh nor cry but a pleading dressed as release.

I know, so dramatic. But that’s what happened.

A few days later, I visited my sister.

The family was living through a tough moment. My little sister, a mother of two young children, had been diagnosed with breast cancer. She was about to begin chemotherapy and I’d flown back from wherever I was to be there and do what I could to help out.

A few weeks earlier, I’d accompanied her to an appointment — at the same hospital, on the same floor, in almost the same room —- where we’d sat with our mother as she moved through the final steps of her life.

It was an absurdly difficult time and the last thing I wanted to do was add to her burden. But we were best friends. And I’d reached the limit of pretending I could deal with it on my own. I needed to tell someone and of course it had to be her.

I’m not doing that well.

It’s reached a point that’s a bit concerning.

She was lying in bed and I was sitting at the edge. I took a moment to look at her, letting the weight of my declaration establish its presence in the air. Then I curled up and snuggled near her lap, like we did with our mother in her big wooden-framed bed when we were kids.

And so I told her. Of course I downplayed it, and excused it, and colored it in all my coping mechanisms. But I did take that first step and said it out loud. And saying it out loud to another person somehow makes it real. It’s been placed on the record and that makes it tougher to ignore and avoid.

I could get you an appointment with Dr. Cohen (our enigmatic family doctor).

My sister had been on anti-anxiety meds for several years. The mix of inherited Jewish neurosis and the passing of our mother, sprinkled with some postpartum issues had led her to an SSRI prescription. It was far from a perfect solution, but it helped.

I hesitated.

You’re too proud to go on meds? She said in her world-famous sharp tongue.

Perhaps, subconsciously. But that wasn’t what gave me pause. I just didn’t want to default to the pharmaceutical model as a first option.

Maybe I should try some other, more natural, things first, and leave that as a last resort.

She shrugged. OK, fine. Like what?

In one of our human ironies, the perspectives that offer us insight are usually only visible in hindsight.

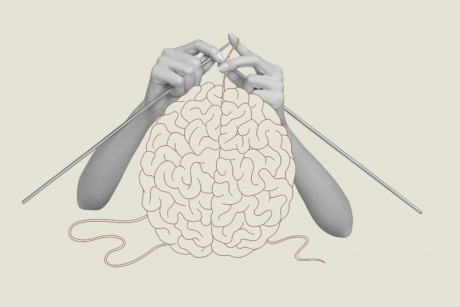

We need to repeat the mistake or behavior enough times to create an identifiable issue — one that we can name and blame and try to correct. The problem is that by the time we’re able to give it a name, it’s already been hardwired into our foundations. It’s made itself a nice little home in our heads, which makes it that much harder to fix, to un-learn.

And that’s how I’ve come to see my mental health “journey”. As a process of un-learning, and re-learning. I’ve realized, in a sort of self-diagnosis, that I’d engrained some bad habits of thought which had turned into fixed defaults of my mind.

That winter I started taking the first steps. I got dressed and walked through the cold and the snow and went to hot yoga class 5 times a week. I’d been doing yoga for years but this was the first time I did it intentionally, with a purpose. I took this thing that I knew was good for me, that always made me more grounded and less in my head — and added it to my routine. Gave it more space. In my life. In my day to day. In my beautiful, mad mind.

Re-learning. Replacing bad habits with better ones.

“Neurons that fire together, wire together”, a fun neuroscience aphorism. Our brains are pattern-recognizing and habit-learning machines, taking data — from the world, from what we feed it — and turning them into things we default to.

What had I been feeding my mind all these years? What is anxiety if not the repeating of a negative, anxious thought?

And so I continued. Bit by bit. Day by day. Year by year. Yoga, by now a mild cliché, is still a wonderful gateway into today’s world of nouveau-spirituality. Suddenly you’re listening to your breath. Noticing a quieting of your mind. Suddenly you’re sitting cross-legged by the yoga studio front desk drinking hot chai and hearing about the conscious festival happening this summer. Suddenly you’re in the Costa Rican jungle eye-gazing with a stranger. Suddenly you’re ecstatic dancing dead sober. Meditating in an open-air temple with 300 fellow seekers. Suddenly those moments of noticing — of hearing the silence — suddenly they’re happening more often, lasting a bit longer.

But it’s not suddenly. It takes years. It takes persistence. And sometimes you get lazy and get off track and have to get back into those better habits once again.

But each time it happens a bit quicker. Because your brain is a habit-learning machine and you’ve been feeding it some better habits. It remembers. You remember. Those moments of quiet and calm. Those brief glimpses into a present experience free of the noise.

A few years ago I hit another rough spot. I’d already been to India and spent a week at a Buddhist ashram, waking up at 5 a.m. and sitting in meditation. I’d already logged hundreds of hours on Sam Harris’ meditation app. But life happens. It accumulates. The decades of bad habits of mind are still there and they are stubborn.

This was years ago, before microdosing psychedelics was on the cover of every magazine. But I’d heard of it, had dabbled in it recreationally. And so I started to learn. My girlfriend bought me a jar of psilocybin mushrooms for Christmas and I made my own microdoses, measuring them by hand from instructions found on Reddit. Adorable.

And what I discovered was a wonderful ally in mental health and a useful tool in my work of re-learning. And an opening to a new chapter in my life and career.

There’s a quote from Micheal Pollan on psychedelics’ effect on the mind. It goes something like this: Imagine your brain as a snow-covered hill and your thoughts as sleds, carving paths down the mountain. The more a thought repeats, the deeper the tracks become. Eventually, you’re always taking those same paths. Psychedelics are like fresh snowfall. Smoothing out the grooves, allowing the mind to create new pathways and travel in new directions.

I won’t get into the neuro-mechanics of it, but psychedelics can help quiet parts of the brain where some of our most neurotic and ego-based thoughts live. And they increase “neuroplasticity” — the ability of the brain to form new neural connections. To learn. New neurons firing together and wiring together.

When people ask me about microdosing and psychedelics, I sometimes use my fancy writer’s voice and say that it “gives me better access to the present moment”. I’m able to go into the database and retrieve the silence. To be here, sitting here, in this moment, and not experiencing life through whatever fucked up filter my mind has constructed for itself.

It’s a wonderful reminder of what’s possible. Yet it’s brief. And fleeting. And soon I’m back in the battle.

But I’m learning. I can feel it. With every step along the path. Every vulnerable conversation. Every downward dog. Every moment taken to check-in. To return to the breath. To see the person in front of me. To remember.

Even by writing these words I’m remembering. And re-learning. Teaching my mind, my lovely, terrible, vicious, scared, fragile, courageous mind — that there is another way.

Come. See. Take a moment. You remember. Look how beautiful it is.